Do You Know Jack?

The Prudential Case Against Suicide

According to an upcoming HBO movie, "You Don't Know Jack," folks. The "Jack" in this case is Dr. Jack Kevorkian, a.k.a., "Dr. Death." The title also means "you don't know anything."

Actually, we know quite a bit about assisted suicide-it's those who insist otherwise that need instruction.

While the movie hasn't aired or even been viewed by critics, we can infer its perspective on Kevorkian from the comments made by its stars, Al Pacino and Susan Sarandon.

According to Pacino, viewers "don't know this guy." Kevorkian "is more than meets the eye...[the film is] a portrait of a zealot. I don't think we see that often."

Kevorkian's "zealotry" also appealed to Sarandon, who said that people who dedicate themselves to a cause at the expense of anything else in their lives "are really fascinating people."

For his part, Kevorkian is said to be "enthused about helping with the film." His lawyer thinks the film won't be "scathing and critical."

I guess not. I certainly doubt that three Oscar-winners-Pacino, Sarandon, and director Barry Levinson-have come together to make a film that won't be at least a little sympathetic to its subject.

What viewers will probably see is a story about a man whose excesses hurt an otherwise noble cause and led to his downfall at the hand of religious zealots.

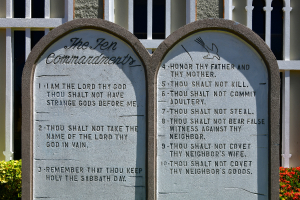

Of course, there's nothing noble or "compassionate" about physician-assisted suicide-and you don't have to be religious to believe that.

No one would call the British magazine Spiked religious or even traditionalist. Yet, it recently ran two pieces about why assisted-suicide should remain illegal. In one of them Kevin Yuill of the University of the Sunderlands makes clear what many assisted-suicide advocates try to obscure: The ultimate goal isn't to alleviate suffering, but to enshrine in law "the right of any person to end their life."

This "right," according to Yuill, threatens the "assumption that human life is valuable."

He calls suicide a "deeply anti-social act" that destroys "possibilities"-not just, obviously, for the individuals themselves, but for others too. Yuill insists that it's this social harm and not what he terms "outmoded religious beliefs" that lies behind the "taboo against suicide."

In the other piece, editor Mick Hume adds that the "right to die" is the result of a "loss of faith-not in God, but in humanity." Hume decries the lack of belief in "the human capacity to transcend the limitations of our lives." In this "demoralized" setting, the wish for a "good death" replaces "the aspiration for a better life."

What Hume and Yuill miss completely is the connection between Christian ideas and the beliefs whose passing they lament. What Hume calls "faith in humanity" is inseparable from the idea of our being created in the image of God. What Yuill calls "possibilities" is derived from Christian ideas about hope.

But that's OK. When it comes to assisted suicide, the next big so-called rights campaign that the left will wage, we Christians welcome good, prudential arguments. So that even non-believers can come to understand the "aspiration for a better life."