Andrew Klavan on how English Romantic poets reveal Gospel in age of atheism, radicalism

When bestselling author Andrew Klavan embraced Christianity at the age of 49, it was the result of what he described as a “deeply literary journey.”

Klavan, an international bestselling author and Edgar Award winner, was attracted to literature at a young age for one simple reason: He needed a male role model.

“I didn't have a lot of male role models in my life, and one of the things that all boys need is male role models, and I found them in literature,” the 67-year-old author told The Christian Post.

“I found them in tough-guy detective stories, in noble men who went into corrupt areas and stayed clean even though they had to deal with corruption and murder. … I thought, 'I want to be like that guy. I want to be a guy who can walk down a mean street and not become mean himself.' … And in doing that, I started to discover that they were all based on mythology and Arthurian legends, and I became very wrapped up in Arthurian legends. And I started to see that Christ and Christianity were at the center of those.”

As a researcher of Western culture, Klavan began to study the Gospels as a teen, much to the chagrin of his Jewish father. Slowly, over the decades, he came to believe that “everything that I believed, everything that I knew to be true, and especially the moral web of life that I knew to be true, was wrapped up in Christianity.”

Though Klavan has few questions about the faith — “I don't doubt much because it took me so long to come to faith that I kind of went down every wrong road and found the arguments against every possible mistake you can make,” he said — there were certain parts of the Bible that didn’t make practical or moral sense to him.

“There are things that we are so used to thinking of as good, like, ‘Turn the other cheek’ and ‘Love your enemies.’ But when I thought about them, I thought, ‘Do I really want to do that? Is that really something I even aspire to?’ If somebody struck me, wouldn't I strike him back? And certainly, if someone struck any of the people I love, I wouldn't hesitate to strike back. The more I thought about it, the more I thought, 'This is a little blurry.'"

So, the host of "The Andrew Klavan Show" on The Daily Wire decided to go back to the Gospels and start from scratch. He taught himself Greek, forgetting everything he’d learned about Christianity from theologians and church traditions, and allowing Jesus to speak for Himself.

As he read the Gospels, he kept hearing echoes of the English Romantic poets like William Wordsworth, John Keats and Samuel Taylor Coleridge — so he went back to the works of those 18th century authors to discover why. He came to discover that the Romantic period, which began roughly around 1798 and lasted until 1837, was eerily similar to today's world.

"It was a period when faith started to fail. It was a period when radical politics were on the rise, a period when people started questioning gender roles, and then the efficacy of marriage, and all of those things centered on a growing sense of unbelief, a growing sense of atheism in the world,” Klavan shared.

“When you lose touch with God, it becomes harder and harder to know what's true, what's right, and who you are. Those are all things that we depend upon God to give us a ground floor on," the author continued.

The poets, he said, started to write poetry in that world, reacting to their environment and recreating the Christian faith and attitudes that had all but disappeared.

"And [they] did it in such beautiful poetic language that it really sticks in your head and really changes the way you read the Gospels," Klavan said.

Because his entire spiritual journey is so “wrapped up in literature,” Klavan said he wasn’t surprised that God pointed him to the English Romantic poets to help him understand Jesus. And reading the Gospels after reading poetry, he said, made the words “come to life in a new way.”

“They say Jesus Christ is the same yesterday, today and tomorrow. And that's true, but our situation changes, our world changes, our consciousness changes,” he reflected. “I felt like these poets were speaking in a modern way about this ancient wisdom, that it was kind of like a bridge that was connecting me to Jesus Christ directly, helping me to get to know how He saw things; not just what He said, but how He saw things, and that just changed the way I read the Gospels entirely.”

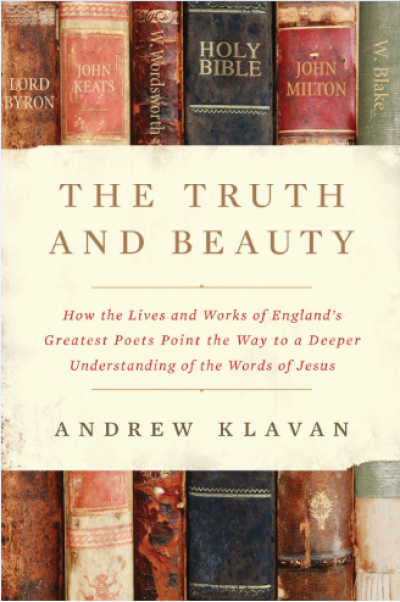

Klavan shares what he learned over the course of this journey in his latest book, The Truth and Beauty: How the Lives and Works of England’s Greatest Poets Point the Way to a Deeper Understanding of the Words of Jesus.

He delves into the personal lives, history and works of poets including Wordsworth, Keats, Coleridge, Frankenstein author Mary Shelley and others to both examine the Gospels and help readers encounter Jesus on a deeper, more profound level.

“What the Romantics did was they showed me how much of what Jesus was doing and what He was saying was based on affecting our consciousness, the way we see the world,” Klavan said. “He says it over and over again, ‘Those who have ears to hear, let them hear, those who have eyes to see.’ He’s trying to show us how He sees the world, and how we can start to see the world like Him and have a little bit of the Jesus mind in us, so the joy that is Him will be in us. That is a beautiful gift to give to someone; the joy of seeing the world through God’s eyes.”

Many of the poets were, as Klavan recounts in his book, “troubled and in pain — they were human.” Coleridge was a drug addict; Keats struggled with depression, and Wordsworth was plagued with physical illness throughout his life.

But Coleridge, Klavan explained, was nevertheless a faithful Christian, a brilliant man who heavily influenced his fellow poets. “And so even though they weren't people of faith, they were guided by the faith, and they came back to it, and they just almost rediscovered it."

For example, the poets helped Klavan understand the mystery of the miracles and what Jesus meant by counterintuitive commands like “Love your enemies.”

“He says, ‘Love your enemies so you can see what God sees,’” Klavan contended. “Even if you see it a little bit, your joy increases exponentially, you suddenly understand, ‘Oh, you, the things that I thought were disappointments aren't disappointments at all; the things that I thought were tragedies have another dimension to them. The things that I expected of the world that didn't come to pass are part of the beauty of the world.’ And you start to have … that wonderful sense that, ‘I get it. This world we're in is broken. But the big world is not broken. A big world is working just fine.’”

“That’s what, I think, the Romantic poets were moving toward in their pain,” he added. “To come to that vision through fallible, pained and yet brilliantly talented people suits me; it actually works for me in a way and brings me back to the Gospels refreshed.”

The poets looked at nature to make sense of their world, yet somehow, Klavan said, “Christian truth looked back at them.”

“Most of the great Christian thinkers from the very beginning have always said, ‘There's a book of Scripture, and there's a book of nature, and in both of them, we can read the glory of God. These things actually are telling the same story,’” Klavan said. “And the Romantics prove that to be true.”

“I think that what you learn from this is, ‘Don't be afraid,’” Klavan added. “I think that’s what nature says to us all the time: ‘Don't be afraid. It's me. I Am that I Am. And I am even in the lightning and the thunder and the disease and the death and the real terrible things that happen.’”

What the English Romantics discovered in an age where science and radicalism were making faith shaky, Klavan emphasized, is that “matter, this stuff we're made out of, is the language in which God speaks to us.”

“The world of the supernatural is this world; it's not a fantasy world. It's not a world where we have to believe a million impossible things a day. It's just living in this world with the intensity and presence and wisdom to see what's actually there right in front of you. And that’s, I think, what the poets teach us.”

Leah M. Klett is a reporter for The Christian Post. She can be reached at: leah.klett@christianpost.com