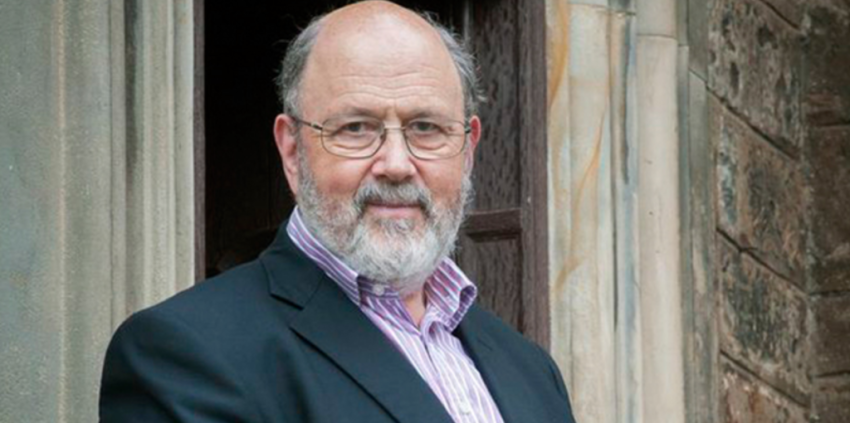

NT Wright on misconceptions about Heaven, the early Christians, and combating biblical illiteracy

Biblical scholar N.T. Wright believes that failing to read the New Testament in its proper context has a devastating effect on both the unity of the Christian church and the theological understanding of God and the world.

“When we fail to care about or recognize the history, literature, and theology of the early Christians, we tend to make them in our own image,” Wright told The Christian Post. “We imagine that they're just like us with our sorts of concerns, yet very often they're not.”

The early Christians, particularly those from the Jewish background, were “celebrating the fact that in and through Jesus, something had just happened, and as result, the world was a different place,” he continued.

“In other words, this was news. Something had happened, something would therefore happen and they were caught up in this new movement. For us, Christianity has collapsed into being a set of good advice about how to go to Heaven when you die. We forget that it started off as news and about something that happened concerning Jesus. If we could reemphasize that, we would all be a lot healthier for it.”

Wright, a retired Anglican bishop and now chair of New Testament and early Christianity at the University of St. Andrews in Scotland, is seeking to combat biblical illiteracy through his new book, The New Testament in Its World: An Introduction to the History, Literature, and Theology of the First Christians, co-authored with Michael F. Bird.

Complete with maps, diagrams, and a series of lectures, the book is intended for both students needing an introduction to the New Testament and any Christian feeling stuck reading Scripture, according to Wright.

“It’s an invitation to walk in the Jewish world, the Greek world, the Roman world of the New Testament,” he said. “What it was like living in those days, why people thought the way they did, why they looked at things the way they did. And then particularly, what can we actually say about Jesus himself, about the Gospels, about the early Christians, about Paul, about the resurrection?”

His goal, Wright said, is to “transform the way that the next generation learns and studies the new Testament, both in seminaries and colleges and in churches more broadly.”

“It’s user-friendly enough for the absolute beginner, but then it'll take people on a long way from there into all sorts of exciting stuff, more than they'd ever imagined,” he said.

The theologian stressed that the ultimate truth in the New Testament is deeply personal, not a mere “how-to” guide when it comes to living a good, moral life. He expressed hope thatThe New Testament in Its Worldwill help modern-day believers study and apply the New Testament with a clarified focus and mission.

“What you find in the New Testament is this deeply personal encounter; the documents themselves are breathing with this sense that we have actually met the living God in the person of Jesus and He's not like we thought He would be. And that's a bit scary, but it's also very affirming and supportive and life-transforming,” he explained.

The New Testament is summed up in Galatians 2:20: “I live by the faith of the Son of God, who loved me and gave Himself for me,” Wright said.

“I think that that sense of a debt of love, which only love can repay, is absolutely at the heart of the New Testament,” he argued. "It's the same whether you fall in love with music or fall in love with great art or fall in love with another person. Then what you do as a result is not a list of rules. It’s ‘I need to plunge myself into this new reality and let it shake me and transform me.’”

According to Wright, the early Christians were “seriously concerned” with unity across cultures, ethnicities, and gender; in fact, the topic of unity is threaded throughout Paul’s letters. But unity as a “Christian imperative” is something the modern world has “largely forgotten about,” he lamented.

“As long as we are a wildly disunited, as we are in Western Christianity at the moment, then the powers that run the world take no notice office. Why should they? Because we're just a babble of different voices,” Wright said.

The early Christians lived as “family,” supporting one another in practical, financial, and realistic ways, Wright contended.

“They weren't just a religion; they were an outward-facing, but inwardly coherent family. I think it's a challenge to us today when in so many of our churches, the people around us rather look like us. We tend to gravitate towards churches where we feel comfortable because it's people of our culture, our socio-economic group.”

The author of more than 80 books emphasized that the New Testament must be read using first-century eyes with 21st-century questions for greater theological and eschatological clarity.

He further delved into his earlier claim that many modern Christians are wrong about the idea of Heaven and the afterlife. The early Christians, he charged, didn’t simply exist on earth to go to Heaven. Rather, they sought to bring Heaven to earth through the Gospel.

“The early Christians were mostly Jews, and they believed that the world was good, that it was God's world, and that God's aim and intention was not to snatch some people from this world to go and live with Him, but so to remake the world, that it would make sense for God Himself to come and live with us, which is what it says at the end of the book of Revelation," Wright said.

“The dwelling of God is with humans, not the dwelling of humans is with God. Of course, that then is the corroboree. But the point is that the New Testament as a whole addresses our culture by saying, ‘Wait a minute, we may actually have been getting our Christianity itself somewhat wrong because we've been imagining the wrong goal to the process.’”

If Christians would “truly study” the Scriptures, they would “see both the theology and the history addressing us in our historical moment, and saying, ‘let's get the theology right,’” he said. “Maybe this would really help with getting the church itself back on track.”

Modern Western culture, according to Wright, has become increasingly “Epicurean.”

He explained: “It’s an ancient philosophy, which is that the gods, if they exist, are a long way away. They don't get involved in our world or we don't get involved in their world. So the best thing to do is let the world run itself and make itself. And if you want to pray towards this God, then fine, but don't expect very much from it. That's, that's Epicureanism in a nutshell.”

He pointed out that Epicureanism has infected contemporary Western thought “in ways that often we don't realize because it's the air we breathe.”

“Christians have done their best in the last 200 years to find a way of dealing with that, but often by appealing to Plato who said that we have souls that really belong in the upstairs world and that we want to get back there as soon as we can,’” Wright said. “The frustrating thing to me as a historian and a theologian is that actually that's not how the early Christians saw things.”

On its own, the simplistic “love God, love people” mantra popular among Western Christians is problematic, according to Wright, as it raises questions about “which god you are worshiping, how it’s supposed to work, and who these people we’re supposed to be loving?”

“In the New Testament when Jesus says the two great commandments are ‘love God and love your neighbor as yourself,’ this is not to the exclusion of the early Christian belief that with Jesus, the kingdom of God is actually arriving on earth as in Heaven,” he clarified. “But most people today in our world simply want to reduce this to an ethic: Here's what I'm supposed to do and then it'll be all right.”

“This book is trying to make people realize that the early Christians were not just a religious movement, they were an everything movement,” he explained. “This was a whole new way of being human. Of course, loving God and loving your neighbor; that's fine, that's in there. But it needs the structure, the scaffolding, the surround support system of all the other things which we get at through the historical study and theological analysis.”

Still, Wright said he’s “optimistic” about the future of Christianity, as he believes people are “searching for something and growing through and past the sterility of post-modernity.”

“It’s one of the reasons our political world is so confused. People are hoping if only they vote this way or support that policy, maybe that will be the way to utopia,” he said. “There is a lot of confusion.”

He also challenged Western Christians to lay aside their arrogance, pointing out that most Christians in the world today are not Westerners and do not speak English as their mother tongue.

“Christianity is flourishing in sub-Saharan Africa, in Southeast Asia, in Latin America, in all sorts of ways,” Wright pointed out. “And I think we in the West need to not say, ‘Oh well they're a bit behind and they need to catch up with us.’ We need to say, ‘Maybe it's we who've gone a bit over the hill and we need to be reminded of where the action really is.”

“I hope and pray that that will be the effect that this book and the study of the New Testament that goes with it will have on people."