Why Owen Strachan thinks critical race theory is a threat to the Church

As a student at Bowdoin College in Maine, Grace Bible Theological Seminary Provost and Research Professor Owen Strachan was so deeply interested in diversity and societal fragmentation he almost minored in Africana Studies.

His interest in the subject never drove him to become an academic expert in the discipline, but in recent months, Strachan has emerged as an expert on social justice and “wokeness” and a strident opponent of critical race theory.

The controversial ideology is defined by the Southern Baptist Convention — America’s second-largest denomination and the world’s largest Baptist denomination — as a set of analytical tools which “can aid in evaluating a variety of human experiences.”

Secular scholars define it as a framework through which they seek to understand how victims of systemic racism are affected by cultural perceptions of race and how they can represent themselves to counter prejudice. Scholarship on the theory traces racism in the U.S. through the legacy of slavery, the civil rights movement and recent events.

Kimberlé Crenshaw, a founding critical race theorist and a law professor at UCLA and Columbia universities, explained the idea to CNN last year.

"Critical race theory is a practice. It's an approach to grappling with a history of white supremacy that rejects the belief that what's in the past is in the past and that the laws and systems that grow from that past are detached from it," she said.

Strachan, who is also a senior fellow with the Family Research Council who once served at Midwestern Baptist Theological Seminary, sees the idea as “demonic."

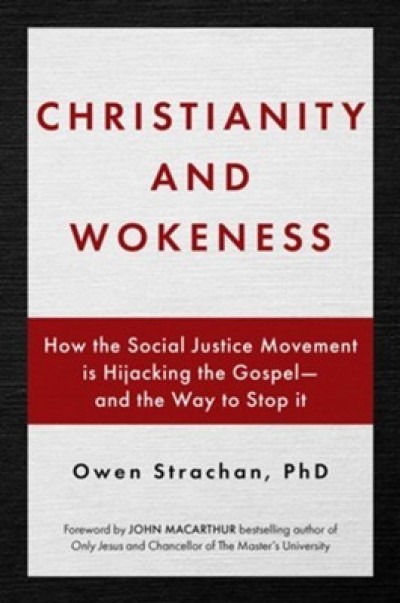

And in his new book, Christianity and Wokeness: How the Social Justice Movement Is Hijacking the Gospel - and the Way to Stop It, he seeks to save the American church from the “slithery hiss“ that he believes to be a threat to Christians and white people.

In seven chapters, spread over 270 pages and a strong foreword from California megachurch Pastor John MacArthur, Strachan presents a studied exploration of critical race theory. He argues it produces a mindset of “wokeness” that seeks to exact reparations from white people for the sins of their forebears. He also goes as far as contending that unrepentant church leaders who embrace it should be excommunicated.

“I think the major problem with wokeness that requires excommunication is that it’s anti-Gospel when you really examine it as a system. It compromises the unity of the truth. It lies about the human person. It says that white people in America are fundamentally oppressors of people of color and that’s not a biblical truth," Strachan told The Christian Post in a recent interview about his book published by Salem Books in July.

"That’s not found in Scripture. That’s injurious and unjust toward white people, and it will violate and compromise the unity of the church."

In the book, he wrote that “[w]okeness is first and foremost a mindset and a posture."

"The term itself means that one is ‘awake’ to the true nature of the world when so many are asleep," the book reads. "In the most specific terms, this means one sees the comprehensive inequity of our social order and strives to highlight power structures in society that stem from racial privilege. In intellectual terms, wokeness occurs when one embraces … Critical Race Theory.”

Strachan says pastors embracing wokeness is problematic because the ideology unfairly maligns innocent white people.

“I know a prominent example of a pastor of a megachurch who took [to] the pulpit and told the congregation that white people should repent for their complicity in white supremacy," he told CP.

"And this was said to a wide range of people, including white people, who had adopted numerous children out of desperate circumstances that had different skin colors than them and were very much trying to love those children and had not been white supremacist toward them in any known way whether in word or deed. That is an example of the evil nature of wokeness. I am here to stand against it, call it out and say it is anti-Gospel."

He said that if he ever heard someone preach like that in front of his family at his church, he would pursue "excommunication."

“If a man stood up in a pulpit and said that before me and said that before my family, I would attempt to talk to him. And I would attempt, if he did not repent of that, to talk to the elders and encourage them to ask him to repent of that. And if he did not do that, I would pursue excommunication as much as I could as a church member. And I would do so with a 100% clean conscience,” he continued. “I pray many people who read this book [will] pursue that action because that is the action that is fitting."

In the Church, he warns that "wokeness is spreading like a cancer and it's training so-called white people who have no racial prejudice in their heart."

"They are literally at great cost, physically, financially and otherwise adopting children out of Christian love and then [a] pastor brings man’s law, not God’s law, into the Church and condemns them as evil," he stressed. "And that is the doctrine of demons, and I’m here to call it out. I do so unequivocally and unapologetically.”

The example was a very personal one for Strachan because his family adopted his sister from South America. He said, “her skin color was not exactly like mine or like several people at our small church, but that did not matter a bit,” he wrote in his book.

“My father and mother loved her, I loved her (and always will), and she loved us. God gave our family a blessing in the form of my sister — a Christian and a woman who loves and serves her family well. And I am so thankful for my parents’ commitment to adoption,” he explained.

Along with his independent research on race, this family dynamic is one of the reasons why Strachan feels he is in a good position to openly discuss an issue that has divided denominations along racial lines.

At their 2020 annual session, the SBC’s Council of Seminary Presidents, comprised of six seminary heads, voted to reject critical race theory as incompatible with their faith while condemning “racism in any form.” The vote caused some black pastors who disagreed with the wholesale rejection of the concept to leave the denomination.

In the wake of that controversy this summer, Southern Baptist messengers affirmed their commitment to racial reconciliation and the sufficiency of Scripture to address issues of race by adopting a resolution that avoided the contentious debate over critical race theory. There had been concerns that messengers would have rescinded Resolution 9 “On Critical Race Theory and Intersectionality.”

In sharing his thoughts on Resolution 9, Strachan believes his book can alleviate the “confusion” about critical race theory among Southern Baptists.

“There is a lot of confusion among Southern Baptists, like evangelicals, like American citizens more broadly, which is why I wrote the book,” he said. “I don’t think most or many Southern Baptists understand what the convention affirmed. Resolution 9 was passed in 2019 under tremendous confusion. And no small amounts of opposition. And the confusion has only continued. The wording ‘analytical tool,’ it certainly appears to me based on James Cone’s black liberation theology, which is anti-Gospel theology.

“…Most people don’t know what it is, and it can sound in neutral terms like it could be a tool. But my prayer is that the Southern Baptist churches will understand the true nature of critical race theory. It’s not a tool of analysis. It’s a tool of division formed by the enemy of the Church.”

In his book, Strachan argues that academic theory and social activism should not supplement Christian thought and practice as the “Bible is sufficient for these things.”

“Simply put, the Bible gives us exactly what we need to find unity, hope and justice in this world. The Bible, furthermore, fuels a life of ‘scriptural reasoning’ — of thinking well about all things according to the conviction that God is God, and everything else is not,” he wrote.

When asked why he quoted 18th-century writer Edgar Allan Poe, who he notes was an atheist, to illuminate “the vengeance of the human conscience” but criticizes Christians who use critical race theory to try to explain how racism works, he admitted that unbelievers “will see different elements of the truth.”

“So someone like me, being a Christian, I’m not necessarily a brilliant economist just because I’m a born-again believer and I have a redeemed mind. God has allowed me to learn through a range of sources, and so the problem with critical race theorists is not that they are not Christian," he added.

"The problem with woke voices is not that they’re not Christian. Some of them are born-again. The problem is that they are not getting the truth right. They are operating by the wrong system. They are operating by a secular system that is godless and bankrupt,” Strachan said.

“I’m not saying you would never quote an unbeliever. That would be fundamentally inconsistent for me to do, given who I quote in my book. I’m saying unbelievers can’t give you the ultimate solution. [There is] no unbeliever you can find, however brilliant … who can give you the ultimate answer to the problem of unity. There are unbelievers who are going to get different things right about our world."

A new study from Arizona Christian University published earlier this month showed an estimated 176 million American adults who identify as Christian, just 6% or 15 million, hold a biblical worldview. More than half of self-identified Christians also reject a number of biblical teachings and principles, including the existence of the Holy Spirit.

And among the 6% that qualified as holding a biblical worldview, strong minorities of that group hold unbiblical views.

For example, 25% say there is no absolute moral truth; 33% believe in karma; 39% contend that the Holy Spirit is not a real, living being but is merely a symbol of God’s power, presence or purity; 42% believe that having faith matters more than which faith you pursue; and 52% argue that people are basically good.

Asked if he would excommunicate these Christians for their unbiblical views, Strachan said he would first try to disciple them.

“There are many people that profess to be Christian who are not truly born again. And so, I think part of what this poll could be capturing is the compromised nature of today’s church."

He said there are "many people today in the Church who say they are a Christian, who believes that white people are fundamentally oppressors of people of color. So that’s an anti-Gospel position,” he insisted.

While his book has received praise from some of his supporters online, Christianity and Wokeness: How the Social Justice Movement Is Hijacking the Gospel - and the Way to Stop It, Strachan rejects one critic online who argues that the book is “a masterpiece in straw man arguments."

“I actually have labored to not produce a book that is a strawman book. Somebody can think that I have done that. I can't control how anyone thinks. What I have tried to do is not live up to the stereotype that if you are unwoke, you simply burn down who you believe are. And that’s why I think a fair assessment of my book would not say that it is a strawman compilation,” he stated. “I hope that they will read my book and see that I’m trying to respect and understand the other side.”