Will the Christian Right survive the Trump presidency?

The 40-year-old Christian Right is showing signs of strain, but also resiliency. Will it survive the Trump presidency? This is the main question animating a new book that brings together some of the foremost political scientists studying American evangelicals and politics.

Many have tried to make sense of evangelical support for the thrice-married casino owner who appeared in Playboy, spoke crudely about his sexual exploits on Howard Stern's radio show, and bragged about being able to assault women because he's rich.

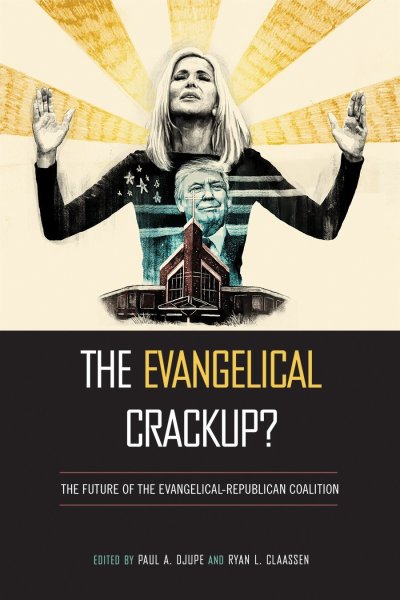

The Evangelical Crackup? The Future of the Evangelical-Republican Coalition, edited by Paul Djupe, Denison University, and Ryan Claassen, Kent State University, contains the contributions of 26 scholars who examined this question, and others, from different angles.

The most often quoted statistic regarding evangelicals and Trump is "81 percent." That's the portion of evangelicals who voted for Trump, we often hear. But there are many problems with that number. It only includes white evangelicals, people who voted, and people who self-identify as evangelical, regardless of level of religiosity, for instance. Another problem is that the number came from exit polls (polls conducted on election day as people left the voting booth).

The great thing about exit polls is that they are fast. It gives pundits on election night evening news some data they can use to analyze the election. But what they gain in convenience they lose in accuracy. We now have better data. This is one advantage of The Evangelical Crackup. The best that election night reports could do was a quick read of poor data. The Evangelical Crackup gives readers a deeper, more accurate and nuanced look at evangelicals and Trump.

In one of the concluding chapters reflecting on the broad themes of the book, Robert Wuthnow, director of Princeton University’s Center for the Study of Religion, writes about the difficulties of studying evangelicals and politics.

What the book is really about, Wuthnow argues, isn't evangelicalism per se but "political evangelicalism," which is only loosely related to actual evangelicalism.

"As it is practiced in the lives of ordinary churchgoers, evangelicalism is a matter of having faith, raising one's children, attempting to be a moral person, dealing with suffering and death, and looking forward to eternal life," he wrote. "Most of these practical day-to-day activities and concerns have very little to do with politics. And this is important to understand because every impetus that may be present for evangelicals to be politically active is countered with an impetus toward focusing instead on faith and family."

Wuthnow also pointed out that, as shocking as evangelical support for Trump has been for many, politically conservative evangelicals have long been pragmatic in their candidate choices and loyal Republicans.

"It seems telling that political evangelicalism in 2012 went for Rick Santorum in the Republican primary, despite his being Roman Catholic; for Mitt Romney in the general election, despite his being a Mormon; and in 2016 for Donald Trump, who seemed to some to be the devil himself," he wrote.

Evangelical elites split on whether to support Trump. Some were enthusiastic supporters. Some were reluctant supporters. Some were silent or agnostic. Others opposed him. But none of that mattered much because evangelicals by and large didn't look to evangelical elites for voting advice anyway. This was the conclusion of chapter 1, "Evangelicals Were on Their Own in the 2016 Elections," by Djupe and Brian Calfano of the University of Cincinnati.

A survey they conducted in 2016 found much ignorance among evangelicals about the positions most evangelical leaders held on Trump. The leaders who were the most well known — Mike Huckabee, Pat Robertson, Jerry Falwell Jr., James Dobson and Tony Perkins — were pro-Trump, while the anti-Trump evangelical leaders — Beth Moore, Russell Moore (no relation) and Michael Gerson — were not well known. A large chunk of evangelicals even misidentified the positions of many of these leaders. Forty percent wrongly believed Perkins was anti-Trump, and the same number wrongly believed that Gerson and the two Moores were pro-Trump.

Most evangelical pastors never mentioned Trump before the election, Djupe and Calfano also found. Only 23 percent of evangelicals reported hearing their pastor talk about Trump. Of those, more than half perceived their pastor to be pro-Trump, but a large minority of them, 38 percent, believed their pastor was anti-Trump. Those who believed their pastor was pro-Trump were much more likely to believe that national evangelical elites were also pro-Trump.

Djupe and Calfano also conducted an experiment to see if evangelicals would become less supportive of Trump if they were exposed to messages critical of Trump from an evangelical leader. Not much shifting occurred. But, in one of the more interesting findings of the book, evangelical men mostly became even more pro-Trump if the critique came from an evangelical leader who was female.

The book's other contributors are: Daniel Bennett, Mark Brockway, Ryan P. Burge, Jeremy Castle, Kimberly Conger, Daniel A. Cox, Kevin den Dulk, Sarah Allen Gershon, Tobin Grant, Robert P. Jones, Geoffrey Layman, Andrew R. Lewis, Ronald J. McGauvran, Joshua Mitchell, Juhem Navarro-Rivera, Jacob R. Neiheisel, Elizabeth Oldmixon, Adrian D. Pantoja, David Searcy, Anand Edward Sokhey, and J. Benjamin Taylor.

The Evangelical Crackup was published Oct. 18 by Temple University Press. You can find it here on Amazon.