Accommodations for Gay Wedding Dissenters Have Rich Precedent in American History, Political Scientist Explains

WASHINGTON — Political scientist Mark David Hall explained Monday that America's history is rich with examples of governments creating religious accommodations for generally applicable laws and asserted that accommodations protecting Christian business owners from having to serve same-sex weddings would be no different.

Hall, a political science professor at George Fox University in Oregon, gave a Monday lecture at the Family Research Council where he explained that although there has been much opposition to the passing of Religious Freedom Restoration Acts in certain states, states have a long history of passing exemptions to laws that forced believers to violate their religious beliefs, even with much support from liberals.

In the last few years, there have been a number of lawsuits brought against Christian business owners who have refused service for same-sex weddings on the basis that it would have violated their religious convictions. Such cases have resulted in business owners being fined ruinous amounts and the loss of their business.

After the Supreme Court ruled last month that it is unconstitutional for states not to issue same-sex couples marriage licenses, Hall suspects the number of cases against religious business owners to rise dramatically.

"There are multiple cases going on throughout the country of this nature — bakers in Colorado and Oregon, New Mexico photographer, T-shirt maker in Kentucky. In my mind, these raise a number of interesting questions, important questions," Hall stated.

"Often times in answering these questions, people engage in hypothetical debates and public policy arguments disconnected from American history," Hall continued. "Historically in America, Democrats and Republicans have partnered to create lots and lots of accommodations to protect religious Americans from generally applicable laws. By one count in the early 1990s, over 2,000 of these. What I want to suggest is that they can provide a guide, or at least some useful information to help us think about this particular case before us today."

Hall began by explaining that early American colonies passed laws that required every adult male to join the militia to protect their colonies from Indian attacks. However, such laws violated the religious convictions of Quakers, whose religion teaches them not to use lethal violence.

"In order to protect the common good and protect religious liberty, what states have done and what early colonies tended to do is they tended to say this, 'We are going to leave the militia requirement in place but if you pay a substitute, Mr. Quaker, we will allow you to not participate in the militia," Hall said. "We will accommodate your religious conviction in such a way that we can still protect the colony and protect the right of conscience."

Hall continued by explaining that the Selective Service Act of 1917, which required the compulsory military enlistment of males aged 21 to 30 years old during World War I, exempted individuals belonging to historically pacifist religions, like Quakers and Mennonites. The law simply required them to serve in noncombatant roles instead.

However, Hall contended that the 1917 law did not go far enough to protect other religious pacifists like Catholics or Baptists from having to serve in the military but explained that the Selective Service Act of 1940 did protect other religious pacifists.

Hall further explained that before America's founding, a number of colonies provided a religious accommodation to a statute that required individuals to take oaths on the Bible in court or before they take public office.

Since the Quakers firmly believe that taking an oath violates the biblical command found in James 5:12, all colonies by the time of America's founding allowed for people to take an affirmation, rather than an oath. Hall elaborated by saying that such a religious exemption is even present in three articles in the U.S. Constitution.

"Is there any serious argument that Quakers have been less loyal than non-Quakers or that they have been less trustworthy in the judiciary?" Hall asked. "In fact, the answer is no and the opposite is true. Quakers became phenomenal merchants in part because their word was their bond. ... States have been able to accommodate this religious conviction without hurting the significant interest on behalf of the state."

As more and more immigrants came to America during the 19th century, state after state passed mandatory public education laws, requiring children under 16 to attend public schools. As homeschooling was non-existent and private schools had a tough time meeting state requirements, Hall said that the Wisconsin Amish objected to sending their kids to public high schools on the grounds that sending their kids to these schools would "corrupt" their children.

Hall explained that the Supreme Court later ruled that the Constitution requires a religious exemption for the mandatory public school laws.

"States have a tremendous interest in making sure their citizenry are well educated but I don't think that these sorts of exceptions actually hurt," Hall said. "In fact, since this era it has become a lot easier to homeschool and private school."

In a case of religious freedom that is more applicable to today's issues with same-sex marriage participation, Hall explained that when states passed laws during WWII that required school children to pledge allegiance and salute the flag, Jehovah's Witnesses objected because they believed saluting the flag was equal to worshipping an idol that is not God.

In 1940, the Supreme Court ruled against the Jehovah's Witnesses, saying that the state interest in "national unity" trumped their religious conviction.

Hall added that about three years later, the Supreme Court tried a similar case in West Virginia v. Barnette where the court "said 'no state, you cannot force these kids to engage in what they considered to be this religious activity against their conscious.'"

Although many others might not feel as though saluting the flag violates their religious beliefs, Hall said it is the individual's deeply-held conviction that is in question, not the convictions of the majority.

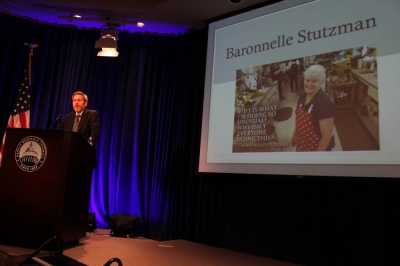

"I have also met a number of good Christians, who think [the Christian florist who refused to serve a same-sex wedding] is wrong. They would say that 'If I was a baker, I would bake a cake for a same-sex wedding.' The question in this case is not what the majority thinks it is what the Jehovah's Witnesses think," Hall argued. "The question with respect to the baker is not what you and I think, but can we recognize that Barronelle Stutzman has a religious conviction against doing this and should we protect that or not?"

"Do we really want judges that protect religious liberty claims that are held by the majority? I would think not," he added.

Hall provided other examples of religious exemptions to laws such as the prohibition of alcohol and drugs and health care mandates for abortion. He asserted that when it comes to gay marriage and religious objectors, there is enough room for laws to protect both the interest of the gay community and the rights of religious objectors.

Although RFRA laws in Indiana and Arkansas received a large backlash from corporations, Hall suggests that states need to focus on passing very "carefully crafted" accommodations that specifically state that religious objectors are to be protected from serving same-sex weddings, rather than just trying to pass very vague religious protections.

"Literally, state codes are riddled with these religious accommodations … all sorts of accommodations all over the place. It seems to me, the best way to address this problem is for states to craft narrow accommodations, accommodations that wouldn't allow a hamburger owner not to serve hamburgers to homosexuals in Indianapolis," Hall said. "We are not trying to provide a general license to discriminate but to protect the relatively few people who have the religious conviction against participating in a same-sex wedding ceremony, a ceremony that many would view as an inherently religious ceremony."