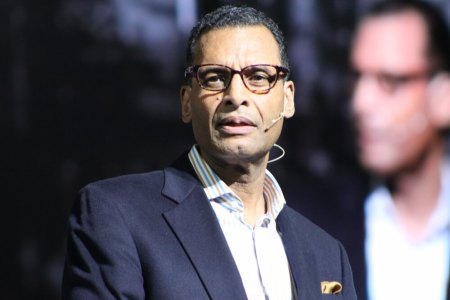

Megachurch Pastor AR Bernard’s dream to combat Brooklyn gentrification inches close to reality

The Rev. A. R. Bernard, pastor of New York City’s largest Evangelical church, the Christian Cultural Center, inched closer to creating an urban village of hundreds of affordable housing units as a formal review of the development has now started after years of planning.

In 2018, Bernard, partnered with Gotham Organization to build 2,100 affordable apartments on his 43,000-member church’s 10-acre parking lot next to Starrett City, the nation’s largest federally subsidized apartment complex. The development, named “Innovative Urban Living,” was initially set to be a mixed-use community, with 13 buildings ranging from two to 17 stories. It was expected to include retail space, a daycare, a school, parking, a trade school and a public park.

After years of back and forth between the developers of the project and community stakeholders, a Brooklyn Paper report said the project has been revised to have fewer residential buildings with fewer floors. The residential space will now cover 2,050 apartments in eight buildings with 12 to 15 stories each. The community’s daycare and public space is expected to be larger and the number of parking spaces in the project has been increased because the location of the development is about a mile away from the closest train station.

"Over the course of the last five years, we have had productive and informative meetings with community stakeholders to gather feedback and collaborate," Bernard told Brooklyn Paper in a statement. "Based on these meetings, we continue to refine the design, programming and housing plan. As a longtime community stakeholder, I am proud to be proposing a vision that provides our community with opportunities for a sustainable quality of life and economic mobility."

In an interview with The Christian Post in 2018, Bernard made it clear that the development was taking aim at gentrification, described by National Geographic as: “A process where wealthy, college-educated individuals begin to move into poor or working-class communities, often originally occupied by communities of color.

“In cities like New York, there is gentrification taking place. Gentrification could be racial, it could be economic. For us it is economic. Individuals who are working-class or in a certain income range are being squeezed out,” he said. “We wanted to respond by creating affordable housing. We didn’t want to do what has typically been done over the last 70, 80 years in America, and that is warehousing people with one income, which perpetuates poverty and perpetuates inner-city condition.”

Developers have designated half of the units in the planned community for the lowest-income potential tenants, those making between 30% to 60% of the area's median income, which is about $36,000 to $72,000 for a family of three. The remaining apartments will go to those making between 60% to 100% of AMI, which is about $72,000 to $120,000 for a family of three.

“What we want to do is create a community and a model that is sustainable,” Bernard told CP. “It is creating community and we want to do it in such a way that is sustainable long-term and a model that we can replicate in other cities across the country.”

While the AMI shown in the plan may seem affordable to some, the area’s former Councilmember Inez Barron told The New York Times in 2018 that the median household income in East New York, where the development is located, has one of the largest proportions of homeless families. The AMI for the neighborhood is $34,512 and more than a third of families there fall below the 30% threshold and are considered “extremely low-income.”

“I think that housing in East New York should be affordable to the people that live in East New York,” Barron, who is a Democrat, said. “We don’t have a significant amount of people that live at 130 percent of area median income.”