Ask Dr. Land: Is it OK for people's religious faith to influence their role in public office?

Question: How should a person’s religious faith, or lack thereof factor into their fitness for office?

As we anticipate President Trump’s nomination of a candidate to replace the late Associate Justice Ruth Ginsburg on the Supreme Court, this is a valid and relevant question to ask. Odds are high that the nominee will be a Roman Catholic, although at least one of the final five is an Evangelical.

In the case of Judge Amy Coney Barrett, the question of her devout Catholic faith was raised rather infamously by Sen. Feinstein (D-CA) when she said, “Whatever a religion is” the “dogma lives loudly within you and that’s of concern.”

That, of course is a highly inappropriate question to ask an American jurist. Judges in the American constitutional system are supposed to interpret the law as it is, not as they would like for it to be. That is the fundamental, thumb-nail definition of what a strict-constructionist, original intent jurist is as opposed to those judges who feel free to look upon the Constitution as a living, breathing document that judges are free to treat as a legal Rorschach test they can see however they like.

If Judge Barrett is a strict constructionist (and she and the other four finalists are), then personal religious faith is irrelevant to their fitness to sit as a judge.

Now, when it comes to politicians running for elected office, the calculus is somewhat different. If their faith is important to them and will impact their positions on public policy issues, they should tell the voters the “what, when, and how” of what that impact would be. Then the voters can decide if that is the Congressman, Senator, Governor, or President they desire.

Perhaps the best example of handling this issue I have witnessed involves Senator John F. Kennedy and his presidential run in 1960. Then Senator Kennedy would have been, if elected, the first Roman Catholic president in the U.S. history. Many people were fearful that the pre-Vatican II Catholic hierarchy would wield influence over a Catholic president that a majority of Americans would find unacceptable.

Sen. Kennedy decided to address the issue directly and forthrightly. In September 1960 Senator Kennedy came to Houston, Texas to address the Greater Houston Ministerial Association (a broad range of Protestant denominations).

It was treated as a “big deal” by the candidate, the ministers, and the media. (Many years later I became friends with the newspaper publisher John Seigenthaler, who was a Kennedy aide there in attendance at this meeting. I asked him how the Senator and the staff viewed the event. He replied that the atmosphere was tense and that the Senator and his staff felt this could very well be a “deal maker” or a “deal breaker.”

JFK wasted no time getting down to the issue at hand. With a hint of irritation in his voice, JFK said, “Because I am a Catholic and no Catholic has ever been elected president, the real issues in this campaign have been obscured. . . . so it is apparently necessary for me to state once again — not what kind of church I believe in, for that should be important only to me — but what kind of America I believe in.”

He then declares his strong belief in separation of church and state. JFK declares, “I believe in an America where the separation of church and state is absolute — where no Catholic prelate would tell the president (should he be a Catholic) how to act, and no Protestant minister would tell his parishioners for whom to vote. . . .”

After declaring his vision of “an America where religious intolerance would someday end — where all men and all churches are treated as equal . . . ,” JFK once again stresses, “I am not the Catholic candidate for President. I am the Democratic Party’s candidate for President who happens also to be a Catholic.” He then declares, “I do not speak for my church on public matters — and the church does not speak for me.”

At this point JFK “threads the needle” as well as it can be threaded, declaring his religion informs his conscience, but “I will make my decision . . . in accordance with what my conscience tells me to be in the national interest, and without regard to outside religious pressures or dictates. And no power or threat of punishment could cause me to decide otherwise.”

Then JFK delivers the ultimate point of his defense. He explains, “If the time should ever come . . . when my office would require me to either violate my conscience or violate the national interest, then I would resign the office; and I hope any conscientious public servant would do the same.”

Frankly, as a Baptist, I could not have asked for a better answer. The pastors were by and large convinced, and the issue of JFK’s Catholicism receded in the public eye, and he won the election a little over a month later.

JFK’s words offer wise guidance for Americans today.

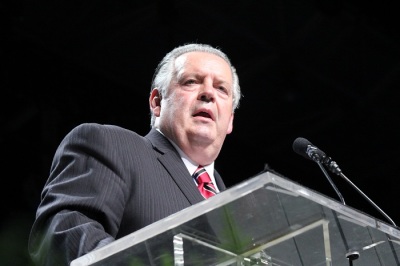

Dr. Richard Land, BA (magna cum laude), Princeton; D.Phil. Oxford; and Th.M., New Orleans Baptist Theological Seminary, was president of the Southern Baptists’ Ethics & Religious Liberty Commission (1988-2013) and has served since 2013 as president of Southern Evangelical Seminary in Charlotte, NC. Dr. Land has been teaching, writing, and speaking on moral and ethical issues for the last half century in addition to pastoring several churches. He is the author of The Divided States of America, Imagine! A God Blessed America, Real Homeland Security, For Faith & Family and Send a Message to Mickey.