Barbarism 2014: On Religious Cleansing by Islamists

World headlines resulted from the April 2014 mass kidnapping of 276 girls in Chibok, Nigeria, eight-five percent of whom were Christian, according to the Nigerian government, and, according to a Boko Haram video, forcibly converted to Islam and designated for enslavement or marriage, or both, to Muslims. What is notable is only the scale of this incident—individual abductions occur regularly in northern Nigeria with the rise of extremism.

A clear symbol of the Muslim extremists' hostility against Christians is the deliberate destruction of its houses of worship, sometimes while they are filled with worshippers.

This crime first attracted world attention in Iraq, in August 2004, with the coordinated bombings of several Baghdad churches by extremists. From then until the Islamic State was established in June 2014, more than seventy Iraqi Christian churches were destroyed by such groups. The most catastrophic was the suicide attack on Baghdad's Our Lady of Perpetual Help Catholic Church during a Sunday Mass in October 2010, when virtually everyone inside was killed or wounded. Since June, the Islamic State has desecrated or closed and repurposed every church in Mosul, along with the monasteries, destroyed innumerable ancient Christian manuscripts, and blown up the tomb of the Prophet Jonah—all in an attempt to eradicate the Christian presence.

In Syria, Kessab's and Maaloula's ancient churches and many others have been targeted for desecration. A third of Syria's churches are estimated to have been damaged during the last three years of civil war, many deliberately.

In Nigeria, Boko Haram has deliberately destroyed more than a hundred churches, and four mosques, in the past two years, according to a statement in the spring by Representative Chris Smith, chair of the US House subcommittee on human rights. In 2011, near the capital of Abuja, the group attacked St. Theresa Catholic Church on Christmas, killing thirty-five congregants. In 2012, the group bombed churches during services on Easter and on consecutive Sundays.

In the last two weeks of May and early June alone, thirty-six churches were reported destroyed by Boko Haram in districts of Borno State that the Christian Association of Nigeria estimates to be eighty percent Christian. "Two hundred more churches were torched in the prior two months alone," reported the Catholic bishop in Borno State in October 2014.

Meanwhile, Egypt saw scores of its Christian churches, like Delga's fifteen-hundred-year-old Church of the Virgin Mary, destroyed over a three-day period in August 2013, when Muslim mobs scapegoated Copts for the military's overthrow of the Muslim Brotherhood government. As my Egyptian colleague Samuel Tadros has noted, it was the largest single attack on the Coptic Church in seven hundred years.

Coptic churches have been targeted individually by fanatical mobs throughout the last decade. In spring 2013, St. Mark's, the cathedral of the Coptic pope, was assaulted during a funeral service by an inflamed Muslim mob. It was to protest these church burnings that Copts marched in October 2011, in what became known as the Maspero massacre, when security forces ran tanks over some two dozen of the peaceful Christian protesters.

One Sunday in September 2013, Pakistani Christians experienced their first large-scale church attack. Suicide bombers attacked the Anglican All Saints Church in Peshawar, killing some eighty worshippers. In March 2013, a Muslim pogrom, incited by a blasphemy rumor, rampaged through Joseph Colony, a Christian neighborhood of Lahore, burning two churches and more than a hundred houses.

Of course, other identifiably Christian institutions, such as schools, convents, and Bible centers, have also been targeted. In May, in the Nuba Mountains of Sudan, the Sudanese air force deliberately bombed Mother of Mercy hospital, founded by Catholic Bishop Macram Gassis. Shortly afterwards, the government in Khartoum announced it would ban the building of new churches in Sudan.

Anti-blasphemy laws are another means by which the most extreme voices in Muslim societies target religious minorities. Christians, along with moderate Muslims, especially the Ahmadis, and members of religious minorities, are often prime victims of blasphemy charges.

In Pakistan, this form of persecution is employed by the state, as well as by extremists within the society. Pakistan has some of the world's harshest blasphemy codes. Amnesty International observed that minorities are disproportionately charged under Pakistan's blasphemy laws, which can carry penalties of death or life imprisonment. A Christian man, Sawan Masih, was recently sentenced to death, and Asia Bibi, a Christian mother of five, remains on death row for blasphemy after being arrested in 2009. It was their calls for Bibi's release that cost Minister for Minority Affairs Shahbaz Bhatti, a Christian, and Punjab Governor Salman Taseer their lives—both of them murdered by fanatics in 2011. Muslim human rights activists, judges, and lawyers who help those accused of blasphemy also put their lives at risk, as was seen in May of this year, when Rashid Rehman, a blasphemy defense lawyer with Pakistan's Human Rights Commission, was murdered, the fourth commission activist to be cut down in recent years.

While Pakistan's government points out that the state has never carried out an execution for blasphemy, some Christian defendants have been murdered while in custody or upon acquittal. Accusations of blasphemy have also grown in the last decade: according to a recent report by the Center for Research and Security Studies, an Islamabad think tank, in 2011 there were eighty legal complaints, compared to only one case in 2001.

The targeting of religious minorities, repeatedly and with impunity, for assassination, forcible conversion to Islam, abduction, church destruction, and blasphemy punishments is a growth industry among radical Muslim movements worldwide, particularly in the Middle East, Africa, and South Asia. Yet the West, perhaps wary of becoming involved in a "clash of cultures," has been slow to respond to, or even recognize, the religious cleansing these types of persecution inevitably lead to.

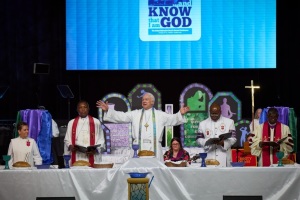

Various policies could be adopted by Western governments to respond to this human rights crisis. The recent "Pledge of Solidarity" put forth by American Christian leaders makes three broad recommendations. The first calls for a new diplomatic post, a US special envoy on Middle Eastern and South Asian religious minorities, which would require the appointment of a prominent figure who has the ear of the president to ensure, among other things, that the concerns of religious minorities, especially their equal rights as citizens, are considered in any eventual peace arrangement in Iraq and Syria. A bill for such a post passed Congress in July 2014 and is now sitting on the president's desk.

The pledge also focuses on the issue of American humanitarian, resettlement, and reconstruction aid, emphasizing that such assistance must actually reach religious minorities and not be diverted by majority groups charged with its disbursement, as happened over the past decade in Iraq.

Finally, it includes a recommendation for a sweeping internal review of foreign aid in light of the situation confronted by defenseless religious minorities and the need for explicit policies to bolster religious freedom and tolerance within the Muslim world through legal and constitutional reform.

These priorities are slowly—too slowly, given the intensity of the violence that has been unleashed against Christians in the Middle East and elsewhere—working their way into US government pronouncements. Following his March 27, 2014, meeting with Pope Francis, for instance, President Obama reaffirmed that "it is central to US foreign policy that we protect the interests of religious minorities around the world."

But in Iraq, where the president has reauthorized the use of American military power to, among other things, "prevent a potential act of genocide" based on religion, there is still no broader US strategy to protect non-Muslims once the present crisis subsides. The vast majority of the two hundred to three hundred thousand Christians remaining in Iraq are now displaced for the foreseeable future. None of the president's policy responses to the religious cleansing of the Islamic State has been calculated to help the survivors to resettle within the Shiite or Kurdish areas of their country now that they are barred from returning to their own homelands; and none has been aimed at helping Christians escape annihilation of their communities.

"Crime against humanity" is not an accusation the US government should deploy lightly. But it should know it when it sees it. And what is taking place now in parts of the Middle East, Africa, and Asia is a tragic eyeful.

This column was originally published at World Affairs Journal.