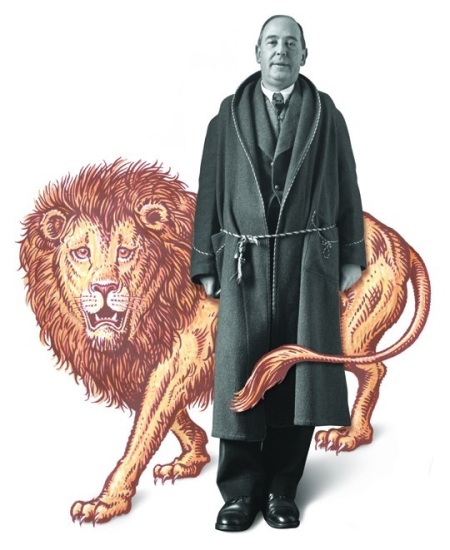

C.S. Lewis: 5 Little Known Facts About Author of 'Narnia,' 'Mere Christianity,' and 'The Screwtape Letters'

Evan C. Rosa comes up with a great list of five things we may have not known about C.S. Lewis. Rosa communicates and curates ideas for Biola University's Center for Christian Thought.

1. He wasn't an Evangelical.

Despite the deep love Evangelicals have for Lewis, he wasn't one. He was a high-church Anglican who sought out the mere Christian middle ground. Lewis' greatest theological work, Mere Christianity, was probably the single most important contribution to Christian unity and ecumenism in the 20th century. Philosopher Peter Kreeft once told me, it's important that Lewis stood in the middle, as that allowed all sorts of Christians to identify with him and gain from his insight.

2. He took long walks.

Lewis frequently went on walking tours with his friends. Sometime walking up to 20 miles a day for several days, stopping at inns, walking was for him a slow and meaningful process - which indicates the pace at which he approached life. He lived life slow enough to enjoy it.

3. He was a romantic.

One of the greatest Christian thinkers of our time was a great feeler. He shows us that an inspired intellectual life is consistent with emotional vibrance and deep love for others. This love is shown most in his unwavering dedication to his brother and the wife of his old age, Joy Davidman. Only a man who loved as deeply as Lewis could write A Grief Observed.

4. He was converted to Christianity by J.R.R. Tolkien.

One evening in September of 1931, Lewis, Tolkien, and their mutual friend Hugo Dyson were talking about myth. It was on that evening that Tolkien taught Lewis that Christianity was "the true myth." Two weeks later, Lewis became a Christian riding in the sidecar of his brother's motorcycle on the way to the zoo.

5. He was haunted by an elusive joy all his life.

Joy factors deeply in the life and writings of C.S. Lewis. His childhood was happy, but tinged with pain and loss (his mother died when he was 9 years old). But for Lewis, joy was more than pleasure, or even intense happiness. Joy was "the End of ends" (Letters to Malcolm, XVII). Joy was fleeting and elusive, but something felt deeply and convincingly by Lewis even before his conversion. Lewis was noticing something a philosopher would call a "telos" or built-in purpose or "end." For Lewis, the human telos is joy. And "Joy is the serious business of Heaven."

(Above illustration: Dave Stevenson, photo: Norman Parkinson/Corbis via C.S. Lewis Facebook)