Campus censorship being driven by students, not administrators: experts

Threats to free speech on public college campuses are increasingly being driven more by students than administrators, a panel of experts who spoke at a virtual Baylor University event said Wednesday.

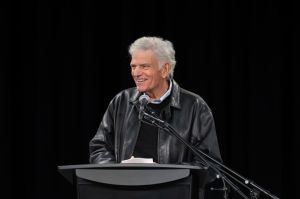

The world's largest Baptist university hosted a webinar titled “Free Speech on Campus: Is it in Danger?” featuring conservative evangelical writer and former attorney David French, openly gay scholar and author Jonathan Rauch and other advocates for free speech.

The event was held in coordination with the Institute for Humane Studies at George Mason University and the Initiative on Faith & Public Life at the American Enterprise Institute.

Notable conservative evangelical writer and former attorney David French, one of the experts on the panel, said he believed there was a recent shift from free speech threats originating from administrators to the threats originating from students.

French recounted how the “speech codes” of many public universities that limited student rights “began to melt away” as they were legally challenged in the 1990s and early 2000s.

“A lot of university censorship was top-down. It was a dean stepping in; it was an administrator stepping in,” explained French. “Around 2014, 2015 you began to see students much more stepping up to demand censorship.”

French went on to state that while he believed there were strong “formal, legal protections” for free speech on campus, “the culture of free speech is less secure than it’s been in a long time.”

“People are more apt to call for your firing, they’re more apt to call for sanctioning,” he continued. “They’re more apt to use the power of social media to swamp you in allegations of racism, sexism, transphobia, etc.”

Rauch, the author of several books and senior fellow at the Brookings Institution in Washington, agreed, saying he believed “we have shifted from an environment where we have a lot of top-down pressure on freedom of speech to a situation where … the administration is defending free speech, often from students who are attacking it.”

“The problem has morphed from legal culture and speech codes to civic culture and peer pressure of students on each other,” continued Rauch, who noted that several polls have shown that most students feel “inhibited” from giving their opinions.

One example was a 2019 report by the Knight Foundation that found 68% of Generation Z students felt that campus climate prevented them from safely expressing their views. In December, the Foundation for Individual Rights in Education released a study of over 478 colleges that found 88% have policies that restrict free speech in some form.

Rauch attributed this shift to many factors, among them the rise of “emotional safety” among students, the reasoning being that “if you are hurt by words this causes pain, it causes suffering in your brain, the circuits that light up are similar to the circuits that light up if you’re subject to physical violence, and that’s a form of abuse.”

Another factor described by Rauch was the belief that restricting “hate speech” can “make hate go away,” when he believed “that’s never how it has worked.”

“People like me have relied on free speech to defend and promote our rights, down through history,” explained Rauch, author of the 2004 book Gay Marriage: Why It Is Good for Gays, Good for Straights, and Good for America.

“Unfortunately, a lot of people, on and off campus, now think that free speech and minority rights are opposed values instead of mutually reinforcing values.”

Other members of the panel included Kristina Arriaga, a former member of the U.S. Commission on International Religious Freedom, and Thomas Chatterton Williams, a writer and visiting fellow at the American Enterprise Institute.

An alternative to censoring different views on campus championed by both Arriaga and Williams was the idea of engaging in dialogue with those who think differently.

Arriaga, a native of Cuba, gave the example of when she was in college and called a racial slur by another student. In response, she opted to talk to the student directly.

“So I walked down the hallway, knocked on the door, and talked to the young woman who had called me this ‘nickname,’” recalled Arriaga. “Turns out, I was the first Hispanic she had ever met.”

“We had this great conversation. We didn’t become best friends, but had I canceled her, I would have betrayed what my family believed when they left Cuba and that is that we’re not wimpy people simply because we’re minorities.”

Near the end of the event, French added that "Christians should be among the most confident advocates for free speech in the entire United States."

"If you're a Christian," stated French, "you should welcome a marketplace of ideas. That should be your playpen because in that circumstance, you're coming into that marketplace of ideas with a position of confidence that you are seeking truth and that you are advocating for truth."

"What I have found in an awful lot of Christian universities is exactly that kind of confidence in the marketplace of ideas," he added. "I have seen it and it even goes all the way back to my own education."