Contrasting Views of Marriage (Part 5): Civil Debate on a Serious Issue

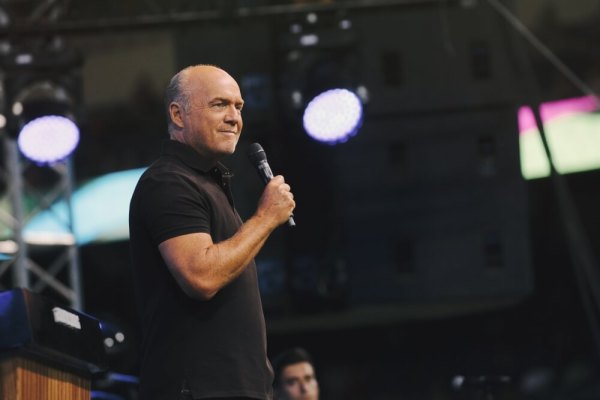

This is the fifth and final column in a five-part series on marriage and originally appeared on the Public Discourse. Robert P. George also co-authored this column.

Although we disagree with each other about the nature of marriage, we are united in the conviction that it is an issue on which reasonable people of good will can and do reach divergent conclusions.

The purpose of our exchanges has been to explore our very different understandings of the meaning of marriage and its implications. We have taken advantage of the fact that we are old friends and longtime academic colleagues who can speak candidly with each other about points of deep difference in a spirit of civility and mutual respect. We hope that these exchanges will, at a minimum, demonstrate to readers that such a thing is possible, even when it involves an issue as consequential and emotionally fraught as the meaning and proper definition of marriage.

Although we disagree with each other about the nature of marriage, we are united in the conviction that it is an issue on which reasonable people of good will can and do reach divergent conclusions. There are arguments and considerations on both sides that deserve to be carefully pondered. Insight and depth of understanding are to be gained from thoughtful engagement, even where agreement remains elusive on the ultimate question: What is marriage?

Our experience in engaging each other reinforces in our minds the truth of a point made by John Stuart Mill in the second chapter (entitled "of liberty of thought and discussion") of his classic essay "On Liberty": One does not fully understand a contested issue, or even one's own position on the issue, until one takes the trouble to consider carefully and sympathetically the arguments that may have led another thoughtful person to a different position.

Critics of what is sometimes called "traditional marriage," that is, marriage understood as a relationship possible only between one man and one woman, frequently fail to engage their opponents because the critics believe that marriage can be understood distinctly as a bond set apart from other forms of companionship by its sexual and romantic component and by intensity of feeling and priority. Our hope is that Professor George's contributions here have helped readers to see that the idea of marriage as a conjugal ("one-flesh") union—an idea long embodied in law and social practice—simply is not captured by such a conception. The real dispute between advocates and opponents of "traditional marriage" is not over whether two men or two women can form a committed romantic partnership, but about whether marriage, understood as an inherently valuable form of association of public significance, is defined by more than committed romantic partnership.

Critics of same-sex marriage frequently fail to engage the position they are proposing to criticize because they assume that their interlocutors wish to decouple the idea of marriage from children and family, and to weaken (or even eliminate) norms of marital conduct (such as sexual fidelity, permanence, and monogamy) that support family stability. Our hope is that Professor Doig's contributions to these exchanges have helped readers to see that it is possible to make an argument for eliminating the norm of sexual complementarity from the idea of marriage while continuing to affirm the social benefit of encouraging other norms long associated with the practice of marriage.

We will not here attempt to recapitulate the arguments we have advanced in support of our respective positions or the criticisms we have leveled at each other's efforts. Those arguments and criticisms are on the table and are fully available for readers to consider. We will, however, say a word about the foundational principles that each of us sees as crucial to a sound understanding of marriage.

Professor George holds that there is a distinctive and inherently valuable form of human association that is realized in the decision of a man and a woman to enter into (and to live out) a conjugal bond, that is, a permanently and exclusively committed relationship in which a man and a woman are united at the bodily as well as the emotional and volitional levels—a union inherently fulfilled by the couple's bearing and rearing children together, though the union is complete even if no children ensue. This multi-level union, naturally oriented to family life, is specially embodied in the "one-flesh" union made possible by the couple's sexual-reproductive complementarity. Marriage, thus understood, is a legitimate concern of law and policy. It is rightly favored and regulated because of its social role in uniting man and woman as husband and wife, and also as father and mother to any children born of their union. This maximizes the likelihood that children are (1) nurtured in the committed bond of the man and woman whose union gave them life and with whom they bear a genetic parent-child relationship and (2) given the benefit of both paternal and maternal influences and care.

Professor Doig holds that the central principles governing the proper design of a society's law of marriage are (1) personal freedom of choice and (2) the most beneficial social outcome. If two adults wish to enter into a bond of mutual care and commitment and have that bond recognized by law as a marriage, they should be free to do so, and their choice should be legally recognized and validated. Persons of the same sex, as well as those of opposite sexes, can enter into such a bond and produce important social benefits, including childrearing, that have long been associated with marriage. Therefore, the norm of sexual complementarity can be eliminated from the law and the cultural understanding of marriage with, on balance, net social benefit. Indeed, legal recognition of same-sex marriage is likely, Professor Doig believes, to increase the number of stable adult partnerships, to the good of children reared by same-sex couples and, indeed, all of society.

Although our views differ profoundly, we have a common motivation. We want the law of marriage to be based on an accurate perception of what is truly for the benefit of men, women, and children. Moreover, we see the social role of marriage, when it is rooted in a sound understanding of human well being, as vital to the common good. We believe that it is crucial for our polity to get the marriage question right, and we hope that exchanges such as ours will assist our fellow citizens in the process of democratic deliberation through which, in a society like ours, such questions are properly resolved.