Controversial Spiked Editor Brendan O'Neill Says Nazis Deserve Free Speech, Draws Applause at NYU

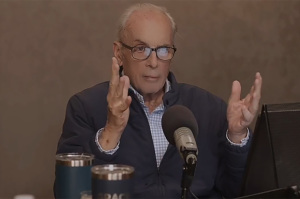

NEW YORK — Once branded the most hated man on university campuses in the U.K., Brendan O'Neill, a controversial free speech advocate and editor for the libertarian British online magazine Spiked, drew applause from an audience at the New York University Law School in lower Manhattan Thursday when he explained why Nazis should be allowed to have free speech.

"The idea that you can have free speech but not for Nazis is such a profound contradiction. That's not free speech that's licensed speech," O'Neill said to applause during the New York City leg of Spiked's Unsafe Space free speech tour of U.S. campuses.

The right of Nazis and their various permutations to freely spread their message has been a controversial topic in recent months as liberal groups have counter protested their rallies.

In August, white nationalist socialists marched through the University of Virginia campus in Charlottesville, Virginia, led by Richard Spencer, a graduate of the school, holding tiki torches ahead of the so-called "Unite the Right" rally to demand protection for a statue of Confederate Gen. Robert E. Lee. They chanted messages such as "white lives matter," "you will not replace us," as well as the Nazi-related phrase "blood and soil."

O'Neill who shared his position during a discussion with a panel of academics on whether the left was eating itself, argued that if Nazis aren't allowed to freely share their views, "That's the end of freedom of speech."

"The second you push someone outside of free speech that's the end of freedom of speech. I have to be really, really, honest here. I'm disappointed to hear even someone who has been sucked into the Kafkaesque censorship of modern day campus make the case for silencing certain voices and there are two basic reasons why you have to have free speech for Nazis," he continued.

"The first is, if you argue for any kind of speech control, the idea that it would be limited just to people you don't like is crazy. History tells you that's wrong," he said.

He then explained that in Britain in the 1930s, there were lots of very positive, inspiring working class uprisings that began against fascists and some "ill-informed people on the left" asked public ordinance stations to prevent fascists from gathering in public.

The move backfired, he said, and public ordinance stations started banning communist and social marches.

"You are signing your own death warrant when you support censorship of anybody. That's such a grave folly," he said.

He also noted that if Nazis are censored it would make it more difficult to challenge prejudice.

"The only way to challenge prejudice is to confront it head on in the public realm and destroy it with argument and reason," he said to more applause.

O'Neil cited an era in the 1920s and early 1930s in Germany when Nazis were arrested and opposed and they won support from the racist sections of the public by presenting themselves as victims.

"If you censor Nazis, you help Nazis," O'Neill said.

While she praised his recommendation in theory, Laura Kipnis, a feminist essayist and professor of media studies at Northwestern University who herself faced Title IX complaints for expressing her opinion on sexual harassment, said it wasn't grounded in reality.

"I understand all the points that you're making because I could make them myself, but you're speaking in a very abstract level," she said.

She noted, for example, on campus there are students who "are not snowflakes but oftentimes have personal circumstances that lead them to feel endangered by political circumstances."

"The classes I teach have one or two students of color facing a class of white kids. And those are real circumstances in a place with real people. ... At the idea level I applaud what you're saying, at the reality level I think it's more complicated than that," she said.

Angus Johnston, a historian of student activism and student government and a professor at the City University of New York, also had a different take on how he believes free speech should work.

"As I was growing up, thinking about the concept of free speech, the place you would always go is Skokie," he said after admitting he is a big "ACLU guy"

The Skokie case refers to a time in 1978 when the ACLU took a controversial stand for free speech by defending a neo-Nazi group that wanted to march through the Chicago suburb of Skokie where many Holocaust survivors lived.

"The example that you would always give that if you were really for free speech you had to be for the free speech of the Nazis in Skokie. And the way that that was formulated was that to be for free speech means to be most of all for the speech of the people you hate the most," Johnston explained.

"The people that you hate the most are the Nazis so that's where you go. I think that's wrong. I think that to be for free speech means that you have to be for the free speech of most of the people whose free speech is most under attack. If the people that you hate the most are relatively privileged in terms of having the ability to avail themselves of their First Amendment rights then they are not the people that you need to be supporting the most," he argued.

"The people that we [should be] supporting the most are the people that are most under attack. It is very easy to defend the people that we really, really hate who are exactly the opposite of us. It is a lot harder to defend the people who we really, really hate, who are kind of like us. The people who are sort of on our team but who we think are completely messing it up. That's the people that's really hard to defend," he said.