Pastor Offers a Third Way Beyond Emerging and Traditional

The traditional church and the emerging church can't seem to get along.

They're often hostile to each other and denounce the other side in their writings and at conferences. But one insider to both sides has made the effort to listen to both positions without cherry picking arguments and bring some understanding to the debate.

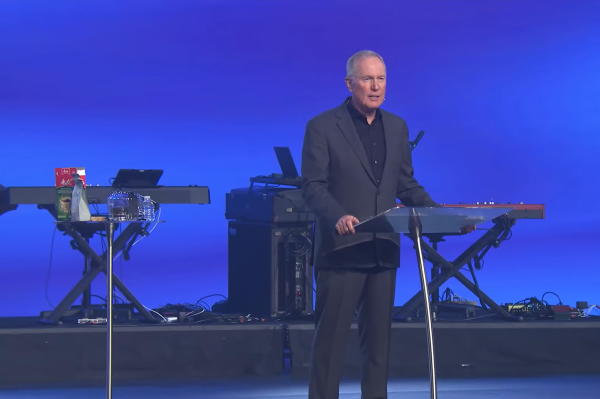

"I just felt like nobody was listening," Jim Belcher, author of Deep Church: A Third Way Beyond Emerging and Traditional, told The Christian Post.

Although criticisms have been thrown left and right for more than a decade, neither side was being fairly represented and attacks were being made using the most extreme cases or worst-case scenarios, Belcher notes in his book.

Just as Calvinism cannot be defined solely by the unfortunate event of the burning of the heretic Servetus or by the claim that John Calvin was a theocrat, the emerging church cannot be narrowed to Brian McLaren or to the denial of truth and the traditional church cannot be solely linked to fundamentalism or sectarianism.

"Anytime if we're going to persuade someone we have to listen well and we have to represent them in a way that they would recognize, not the way the critics would recognize," Belcher said.

An insider

Belcher, 44, was part of the emerging church circle even before the term "emerging" was coined. In the late 1990s, he teamed up with Mark Oestreicher in ministry to launch an alternative service for Generation X; started up weekly conversations in Southern California with such young pastors as Rob Bell; and attended a Gen X conference where Mark Driscoll first started the buzz about postmodernism when many were still unfamiliar with the term.

All of them were not satisfied with the way church was being done. As Belcher wrote in his book, "We were young and idealistic, trying to devise the perfect church, or at least one that was better than what we had known."

Although he was an insider to the emerging church discussion since its inception and his friends and former colleagues are now major players on the emerging stage, Belcher had serious qualms about the direction some were headed. He agreed with them when assessing the problems in the traditional church but was uneasy about some of the answers to the questions they raised.

He was caught in between but he was comfortable with that ambiguity. It allowed him to learn from both camps, he wrote.

Today, Belcher leads a church within a historic Protestant denomination – Presbyterian Church in America. It's not so much that he gave up on the emerging church and returned to the traditional route, but it was his attempt at finding "a third way," or what he calls "the deep church" – a phrase he borrowed from C.S. Lewis.

Is unity impossible?

In his quest to find the third way, he was motivated to help heal the divisions in the church. And with a foot in both camps, Belcher was able to move beyond the assumptions and rhetorical shoutings and present both sides without any bias – at least judging from the feedback he's been getting.

"What I've been absolutely amazed is that people on both sides, even if they disagree with my third way, really are not disagreeing with how I represent them," Belcher noted to The Christian Post. "They're all feeling like they were heard."

When writing the book, Belcher did not rely solely on his past experiences with those in the emerging camp to present their convictions. He read dozens of books (some three times over), perused many blogs and jumped on airplanes to visit and spend time with emerging church leaders.

He boiled down all their dissatisfaction with the traditional church to seven main categories of protest: captivity to Enlightenment rationalism; a narrow view of salvation; belief before belonging; uncontextualized worship; ineffective preaching; weak ecclesiology; and tribalism.

The familiar debate on tribalism goes like this:

The emerging voices blame the traditional church for being sectarian, having no desire to reach people in postmodern culture, being uninterested in the biblical call to be creative in the arts and having sold out to Christendom (the church-state political alignment). Because the church has aligned itself with the state, it has a terrible reputation in society. In short, the traditional church has become irrelevant to the cause of Christ in the world.

The traditional voices argue the emerging church has succumbed to the worst forms of syncretism, becoming indistinguishable from the postmodern world they say they want to reach. They have assimilated, become worldly and lost their ability to be salt.

After studying arguments from both sides, Belcher found that the emerging church is "thinking deeply about how postmodernism and the gospel of the kingdom are to interact, and how Christians can create and transform culture."

As Belcher cites, Steve Taylor contends in The Out of Bounds Church? that the traditional church's view of God's creation and the world has led them to confuse the world with worldliness. Though the Bible rejects worldliness, it does not condemn the world, which, of course, includes God's creation. Some strict fundamentalists in the traditional church show disdain toward creation and culture, and yet in doing so become proud, arrogant and uncaring.

"Taylor correctly calls the church to recapture a biblical view of the world which allows us to engage culture in a way that honors God's calling on our lives – to be missional, or what Jesus calls 'salt and light,'" Belcher wrote. "Since God has not given up on his good creation, neither should we."

Taylor encourages creating culture, mainly in the area of music and art.

Pastor John MacArthur pushes back saying the emerging church's biggest problem is their refusal to shun the world, Belcher cites. They labor under the false impression that in order to win the world for Christ, they have to gain its favor.

Pointing out weaknesses in both arguments, Belcher says "the traditional church is pacifist in the area of culture but not in the realm of politics, and the emerging church is pacifist in the realm of politics but not in the realm of culture. Both sides suffer from the lack of a comprehensive view of Christ and culture that treats the private and public realms in a consistent manner."

Belcher presents a third way. In a nutshell, be distinct from the surrounding culture but also engage it.

The PCA pastor offers a third way in greater detail for each of the seven protests he lays out. He uses his church, Redeemer Presbyterian Church in Newport Beach, Calif., as an approximation of what that third way, or the deep church, looks like but he insists that Redeemer is not the model.

"It's a starting point," he said. "It's not the end all and be all. I don't think we've got it all figured out."

Deep church may not be the answer to reconciling the traditional and emerging camps, but he's hopeful that his book has at least broken down some of the distrust from each side.

"They're not as threatened by each other," he said. "I think that's good for the church."

Belcher wants more than anything, unity in the church.

"What I'm after is getting the church to be united around deep church or mere Christianity, as C.S. Lewis said first, so that we can work together and move into mission and really present a unified front to a watching world instead of one that's always arguing and complaining," he said. "Why would someone out there want to join a family that's always arguing?"