Editing DNA of Human Embryos 'Morally Permissible,' UK Ethics Body Says; Other Bioethicists Push Back

A British ethics body has declared that it may be "morally permissible" to edit the genes of a human embryo based on what their parents think is best for the future child.

The Nuffield Council on Bioethics said in a report that altering the DNA of a human embryo could be ethically right provided that the edits are in the child's interests and did not contribute to the types of inequalities already plaguing society, according to the Guardian Tuesday. The report does not advocate that the law be changed but argues that more research and debate occur.

"It is our view that genome editing is not morally unacceptable in itself," said Karen Yeung, a University of Birmingham professor of law, ethics and informatics who chaired the Nuffield working group.

"There is no reason to rule it out in principle."

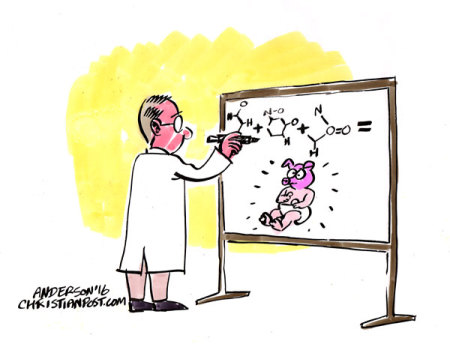

Not everyone has responded so favorably as it has received pushback from critics who assert the report is opening a dangerous door that will yield abuses and inequalities of the kind bioethicists purport to condemn. Some are concerned that while much of the talk surrounding the practice of gene editing is related to altering DNA to prevent genetically-related diseases, allowing this practice will lead to designer babies — parents choosing to give their child blue eyes if they want — and the medical industries that will profit from their creation.

Matthew Eppinette, executive director of the Center for Bioethics and Culture Network, believes the moral framework the Nuffield working group used to arrive at their approval of the practice is inadequate.

"Most often, it seems that ethical questions in situations like this focus on consequences, of balancing harms and benefits, of whether a particular action or treatment will, on balance, make things better or worse. Indeed, this is an important part of decision making. But it is only a part," Eppinette said in a Wednesday email to The Christian Post.

"I would argue that consequences should not be the only, the overriding, or the most important factor."

He referred to the work of deceased Christian ethicist and Princeton University professor Paul Ramsey, who in his book The Patient as Person: Explorations in Medical Ethics contends that there might be valuable scientific knowledge to acquire but is "morally impossible to obtain."

"There may be truths which would be of great and lasting benefit to mankind if they could be discovered, but which cannot be discovered without systematic and sustained violations of legitimate moral imperatives," Ramsey wrote.

And those moral imperatives include care for the most vulnerable among us and acknowledging our human limitations, Eppinette wrote last year. He further stressed, citing the work of Gerald P. McKenny, author of To Relieve the Human Condition: Bioethics, Technology, and the Body, that we must consider "what our bodies are for, how suffering relates to these purposes, and how technological medicine assists or hinders these purposes."

Eppinette told CP he thinks the Nuffield Council seems to have lost sight of all of this and asserts that germline genetic editing and engineering "should be rejected by science, by society, by each and every one of us."

Likewise, David King, director of Human Genetics Alert, called the Nuffield working group "an absolute disgrace," as noted in the BBC Tuesday.

"We have had international bans on eugenic genetic engineering for 30 years. But this group of scientists thinks it knows better, even though there is absolutely no medical benefit to this whatever. The Nuffield Council doesn't even bother to say no to outright designer babies. The people of Britain decided 15 years ago that they don't want GM food. Do you suppose they want GM babies?" he asked.

The Nuffield report urges the government to establish a new body ensuring that as many perspectives as possible are involved in public debate about what ought and ought not be permitted in this arena.

"We are very clear that what we need to have is as wide a discussion about this issue as possible," said Jackie Leach Scully, who co-authored a report and is a professor of social ethics and bioethics at Newcastle University.

Yet Marcy Darnovsky at California-based Center for Genetics and Society in California warned that what the Nuffield Council says versus what their words will yield are different. She argued that should reproductive gene editing be allowed it would also be used for cosmetic and enhancement purposes.

"They dispense with the usual pretense that this could — or, in their estimation, should — be prevented. They acknowledge that this may worsen inequality and social division, but don't believe that should stand in the way," she said.

"In practical terms, they have thrown down a red carpet for unrestricted use of inheritable genetic engineering, and a gilded age in which some are treated as genetic 'haves' and the rest of us as 'have-nots.'"