Exploiting Poor Prisoners: $120 Will Only Buy a Tube of Toothpaste in Some Prisons

Advocates for prison inmates and their families are speaking out against a growing network of state prisons across the U.S. that they say are passing on prison revenue costs to the inmates' innocent families and friends. The families are forced to use high-cost, third-party prison banking companies and high-cost phone vendors that share a cut of their profits with state corrections agencies.

An investigation by The Center for Public Integrity reveals that in order to transfer money to their incarcerated loved-ones, family members of 70 percent of the inmates in American prisons are required use certain online prison banking companies, like JPay, Inc., which charge unreasonable percentage fees to use their service on top of access charges. These companies, in turn, give a cut of the profit back to the prisons and corrections agencies.

A prime anecdotal example, the report highlights, is the case of one mother of a Virginia inmate, who is serving a 20-year sentence for armed robbery. Before, Pat Taylor would send money orders to her son with no problem with a cost of about $2 per money order. But when Virginia stopped accepting money orders and forced her to place money into an online account through JPay, she noticed that it cost her much more to send her son some extra spending cash.

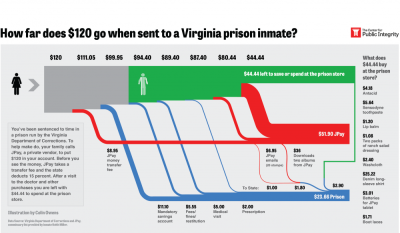

In order for Eddie to be able to spend $50 on basic needs, Taylor said she has to debit at least $70 into the account to accommodate for the base $8.95 transfer fee and the percentages that the correction agency and company will take out. With a $120 deposit in Virginia, prisoners will actually only receive $44.44 after JPay gets $51.90 and the prison takes out its share of $23.66.

If a family member places $130 into an account with JPay for a Florida prisoner, the prisoner can't buy much more than toothpaste. The report finds that the corrections agency will automatically deduct: $25 booking fees, $3 a day or $90 a month for subsistence fees and medical co-pays, $8.95 JPay transfer fee and nearly $6 for a tube of toothpaste. After all that, the inmate is left with close to nothing in the account.

The investigation finds that prisons in 32 states are using JPay and that transfer fees can be as much as 35 to 45 percent depending on the state. Additionally, prison phone companies, like Securus Technologies, which have been hurting family pocketbooks for longer than prison banking vendors, also charge access fees and an approximate a dollar-per-minute rate that is higher than normal phone rates.

With studies showing that a majority of prisoners and prison families are not well off financially, Craig DeRoche, executive director of Justice Fellowship, the policy arm of the inmate advocacy group Prison Fellowship, said that family members are strapped by these policies. In many cases, they are forced to choose whether to pay for other necessities, like bills and doctors' visits, rather than send their imprisoned family member some money or call them.

Correction agencies' policies that allow these companies to charge such high costs for their services only deters from the society's goals for these inmates, DeRoche noted.

"To the extent that we make helping the community by helping and participating with someone that is in prison unavailable through fees, we work against our own interest as a community because we make it less likely that person will turn away from a life of crime," DeRoche said. "The prisoner isn't paying these fees, their families are. What it does is it sways the family from the level of involvement that the community wants them to have with the prisoner. The type of involvement that helps them re-enter society and move away from a life of crime."

DeRoche said that although it has been traditionally a responsibility of state taxpayers to fund state prisons, prison budget shortfalls in the last decade have paved the way for corrections agencies to accept JPay's offer of a profit-sharing prison banking system. Although JPay lobbied to get the contract to serve all the Federal Bureau of Prisons' 216,000 inmates, that contract is currently through Bank of America.

The prison banking scheme has not yet seen reform laws hurt their profits, but the Federal Communications Commission acted in 2013 on a petition from inmates complaining about the high prison phone rates and placed a cap on the rates charged by companies for interstate calls.

Although these caps do not apply to intrastate calls which are at the jurisdictions of the public utilities within the states, the FCC's action paved the way for states to put in place reform laws on intrastate calls.

"Now there is an effort in the states where the states are now starting to step forward and put in place their own ban on exacerbated fees on communication costs," DeRoche said.

DeRoche said that reform policies addressing the stranglehold that JPay has on state prisoners are not as far along as the communication reform policies. But he believes that going into the 2015 legislative sessions there will be an increased interest in promoting prison banking reform policies.

"Does this type of policy work exist? The answer is yes. Is it met as far along with the banking fees? The answer is no. This is an evolving issue that I think that many of the advocacy groups were unaware of," he said. "At this time, the most of the legislatures have adjourned for the year. I believe this will be a larger topic going into 2015 as more and more interest gains around it."

Although JPay commits a lot of resources toward lobbying government interests, DeRoche said that level-headed politicians should be able to make the wisest decision once they are presented with all the facts.

"As a former legislator, I know that businesses lobby for all sorts of things but the character and the integrity of the people that are in office is that they usually try to do the best thing when facts are presented to them," DeRoche said. "What we want to do is find out what is going on. Where possible, put in place policies that will improve the families' abilities connect with, communicate with and support that prisoner moving away from a life of crime."