From prison cells to Ph.D.: Advocates push to restore college access in prison

The next step

There are different avenues that advocates and lawmakers can use to restore Pell Grant eligibility for people in prison.

Among them is a stand-alone bill called the REAL (Restoring Education And Learning) Act.

The bill was introduced in the U.S. Senate by Hawaii Democrat Sen. Brian Schattz. In the U.S. House, the bill has received “unprecedented” bipartisan support with over 40 co-sponsors, according to Rice-Minus.

There is bipartisan momentum around the criminal justice reform issue after the December 2018 passage of the FIRST STEP Act, a bill considered by many to be the most significant criminal justice reform legislation passed in decades.

To many justice reform advocates, the REAL Act is a “logical next step.”

“We believe that this is the next step,” Andrisse explained. “That was the first step and we believe that education is that second step for the next step. This is the next thing in line for criminal justice reform.”

Despite bipartisan support for the REAL Act, Rice-Minus doesn’t realistically see the stand-alone bill receiving a vote on the House or Senate floor in 2020.

“I think it can be attached to something or be used as a provision of a larger bill. But I think just given the niche issue that it will be unlikely to get floor time,” she said. “That being said, I think that it’s a very big accomplishment that we have had so much unprecedented bipartisan support for this issue in particular.”

“We have been hoping for another primary legislative vehicle to attach the REAL Act or something similar to such as the Higher Education Act reauthorization."

Senate Health, Education, Labor and Pension Committee Chair Lamar Alexander included Pell restoration in his Student Aid Improvement Act.

Although the Student Aid Improvement Act has bipartisan pieces of Higher Education Act reauthorization included in it, it does not hit on all the issues desired by the committee’s ranking member, Democrat Patty Murray of Washington.

“They didn’t see Democratic support come onto that bill,” Rice-Minus said. “The fact that this is a smaller breakthrough in higher education may also mean that there is still enough goodwill for them to come back together and talk about some other pieces before Chairman Alexander’s retirement.”

Rice-Minus noted that there were meetings on Capitol Hill in December to determine possibilities for 2020.

“For us, that includes looking at another deal on higher education reauthorization,” she said.

There has also been some debate over whether Pell restoration should include restrictions. For example, one idea would ban people serving life sentences from accessing education grants.

Prison Fellowship, the nation’s largest evangelical prison ministry, believes there should be no restrictions if Pell is restored to prisons.

“We have a large population in America of people that will serve the rest of their lives in prison. We ask ourselves, do we want to make part of the solution part of the problem inside of prison?” Prison Fellowship Senior Vice President of Advocacy and Public Policy Craig DeRoche asked.

“You can expect somebody to behave when they leave prison how they did when they went to prison,” he said. “And what we found is that if you invest in the people that are going to be there for the rest of their lives, they can be great teachers and great mentors, if you give them the tools.”

Trouble accessing education outside of prisons

Once released from prison, formerly incarcerated individuals often have a hard time getting approved to attend or take classes at colleges and university campuses.

Andrisse found this to be the case when he was interested in pursuing a doctorate upon his release.

While in jail, Andrisse’s father died from diabetes. That inspired Andrisse to do all he could to study the disease while in prison.

Before going to prison, Andrisse earned his bachelor’s degree. And in prison, he spent his time reading scholarly and scientific articles to feed his passion for knowledge about the illness that took his father's life.

After prison, Andrisse was rejected from every program that he applied to except one. The school that accepted him, he said, is the same one where his longtime mentor was a member of the admissions committee — St. Louis University.

“It generally takes about six years and I was able to complete it in four years,” Andrisse said. “And I also completed an accelerated MBA as well.”

Andrisse was in a bit of a privileged situation, however, as other formerly incarcerated people don’t typically have the benefit of a mentor on an admissions board to help them get accepted.

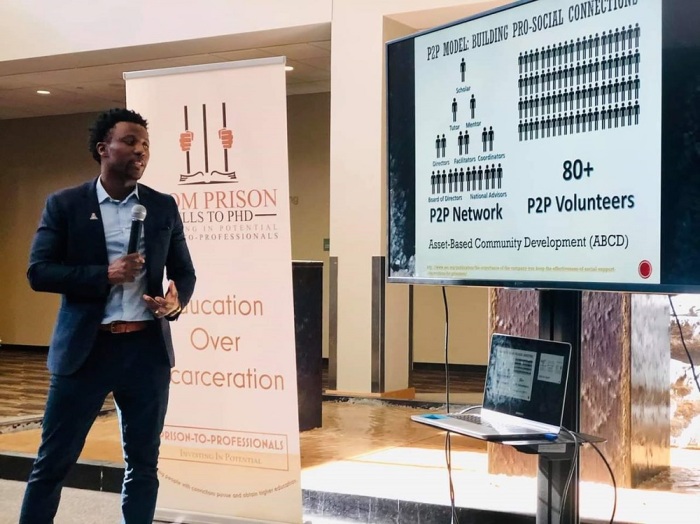

“That was the motivation behind starting P2P,” Andrisse said. “I do probably two to four speaking engagements weekly. It never fails that someone will come up to me and mention that I'm this anomaly because of how intelligent I am.”

“It's one of those things that's meant as a compliment but it really isn’t because it's saying that you're the only smart one among mostly dumb folks,” Andrisse said. “I had this mentor in my life and a support system. And so that is what my organization provides.”

In recent years, there has been an increase in institutions of higher learning becoming more accepting of formerly incarcerated students on their campuses.

In 2016, Nyack and dozens of other institutions joined onto a White House pledge to ensure that people who have been involved in the criminal justice system have a “fair shot at a second chance” by adopting fair chance admission practices. One such practice is the “Beyond the Box” initiative for schools to make informed admissions decisions before taking into account criminal history.

Andrisse's organization, P2P, works with about 100 current and formerly incarcerated individuals each year to help them find educational opportunities and college loan assistance. P2P also provides them with SAT/GRE prep, internships, college readiness workshops, leadership training and scholarship opportunities.

The average grade-point average among those who have gone through the program is 3.75, according to Andrisse. About 95 percent of students the group has placed into programs of higher education have received employment, he noted.

“I see my scenario playing over and over through all of our scholars,” he said. “They're given this opportunity after being told that they would never have any opportunity and left kind of hopeless. Now they're given this second chance and they run with it.”

One participant in the P2P program is going to Massachusetts Institute of Technology to be an astrophysicist, Andrisse said.

“I know very intimately that there is an abundance of talent and potential that we're locking behind these walls,” he said. “But the narrative, unfortunately, is the narrative of what was prophesied on me.”

Follow Samuel Smith on Twitter: @IamSamSmith

or Facebook: SamuelSmithCP