Henry Louis Gates: Black people didn’t embrace Christianity to get to Heaven

While it was a “distant motivation,” black Americans did not embrace Christianity to get to Heaven, according to renowned historian, filmmaker and public intellectual Henry Louis Gates Jr.

“Why did they do it? Did they do it to get into Heaven? No. Is that why they embraced religion? Well, I think that that was one distant motivation, and that's part of, you know, their belief in Christianity. But I think that they did so that they could believe in another kind of future here on Earth,” Gates said in an interview with NPR published Monday.

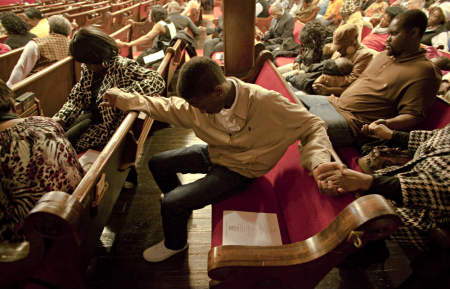

Gates, whose new book, The Black Church: This Is Our Story, This Is Our Song, released Tuesday, explores the black embrace of Christianity, also explores the 400-year-old story of the black church in America in an intimate four-hour docuseries of the same name. The series premiered on PBS Tuesday night.

He delves into the story of the churches built by freedmen in the North in the 1800s and the black Protestant traditions that thrived after the Civil War in the South emerging as the backbone for black communities in the U.S., and the cultural shifts that took place as a result of the Great Migration.

“The black church has been the heart and soul of the black experience generally but of black politics, from the abolitionist movement to Reconstruction politics to the Civil Rights Movement. In fact, if you think about it, without the church, there wouldn't have been a Civil Rights Movement,” Gates said. “And the church is still relevant to politics today, as we've just seen with the critical role played in the nomination and election of Joe Biden and Kamala Harris and Senator Ralph Warnock, himself a pastor at Martin Luther King's former church, Ebenezer Baptist in Atlanta.”

Last month, Warnock was elected as Georgia’s first black senator, defeating Republican Sen. Kelly Loeffler in a closely contested runoff.

While the black church still maintains a strong influence on black culture and politics, its influence has been divided by more secular systems that emerged after the assassination of Martin Luther King Jr.

“After the tragic assassination of Martin Luther King Jr., the church was being challenged by the black power movement, particularly the Black Panthers, who thought that, to quote Marx, the embrace of Christianity was the opiate of the people. But more and more secular African Americans ran for public office. And why was that possible? Well, at one time, the way to emerge as a leader in the black community was through the church. It was like going to the role at the Harvard Business School to Wall Street,” Gates explained. “But ... all that started to change in the late 1960s with affirmative action. The church was the funnel to broader roles of leadership within the black community. But those institutions that enabled leadership diversified because the larger society opened up in the late '60s and the 1970s. Why — out of goodwill? No, because of the demands made by black people right after the murder of Martin Luther King.”

The PBS series is featuring renowned participants such as media executive and philanthropist Oprah Winfrey; singer, songwriter, producer and philanthropist John Legend; singer and actress Jennifer Hudson; Presiding Bishop Michael Curry of The Episcopal Church; gospel legends Yolanda Adams, Pastor Shirley Caesar and BeBe Winans; civil rights leaders the Rev. Al Sharpton and the Rev. William Barber II; scholar Cornel West; and others.

“Our series is a riveting and systematic exploration of the myriad ways in which African Americans have worshipped God in their own images, and continue to do so today, from the plantation and prayer houses, to camp meetings and store-front structures, to mosques and mega-churches," Gates said in a statement. "This is the story and song our ancestors bequeathed to us, and it comes at a time in our country when the very things they struggled and died for — faith and freedom, justice and equality, democracy and grace — all are on the line. No social institution in the black community is more central and important than the black church.”