'Girl at the End of the World' Author Views Similarities Between Fundamentalist Christian Cult and Church Dynamics

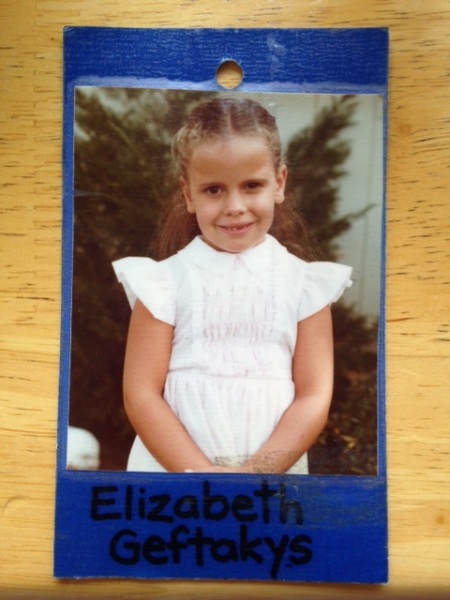

Author Elizabeth Esther's Instagram feed reveals images of her jumping on the trampoline, her daughter at a recent ballet performance, glasses of wine, and photos of her smiling twin girls. Other than pictures of her recent book launch party, there is little to suggest that she belonged to a Fundamentalist Christian cult just a little more than a decade ago.

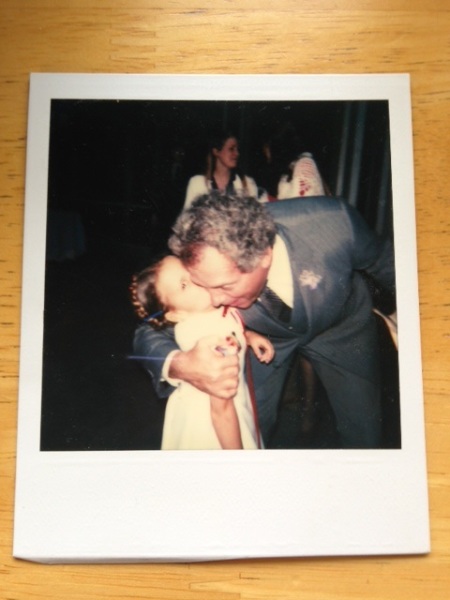

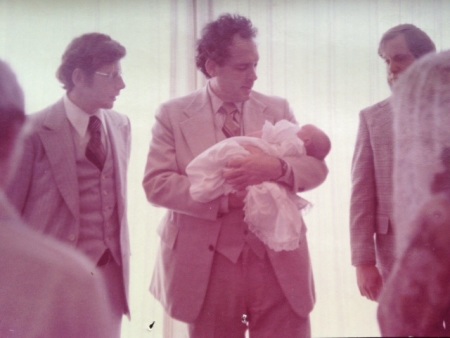

Headed up by her grandparents, the Assembly religious movement that Esther was a part of not only believed that the Apocalypse was imminent, but also sanctioned aggressive corporal punishment for infants and children, strict gender roles that went as far as policing tones of voice, and family street preaching.

Several years after marrying a man who had also joined the cult, Esther and her husband left the church after they confronted her grandfather about alleged abuse that he and the community had covered up. Esther recently released, Girl at the End of the World, a memoir about her childhood and young adult years in the community.

What prompted her to share her story publicly after years of attempting to distance herself from her past? Esther tells the Christian Post that in the years between her departure from the Assembly and her arrival at Catholicism, she had witnessed far too many churches' organizational structures mimicking her former cult.

"I began to realize that while my experiences were on the extreme side and unique in that regard, a lot of the things I learned from those experiences were universal and happened in a lot of churches. It became even clearer to me when I had gone through a phase of visiting a lot of churches that similar dynamics were at play throughout much of evangelical Christianity," said Esther.

For Esther, the theological tenants of a given church unnerved her less than the actual governance infrastructure of the church.

"It's not about doctrine. It really isn't," said Esther. "So many Christians believe much of the same thing. It's about structure and systems and how a church was set up and how it operated and whether there were governing boards and whether there was accountability."

Esther characterizes the Assembly as one that consistently granted her grandfather the final word on interpreting the Bible and overseeing the community with few checks and balances to counter his extreme policies. For many years, he had his followers convinced that the world would end in 1988.

Once outside of the cult, Esther became quickly attuned to spotting this autonomy in other congregations she visited, most recently authoring a blog post analyzing whether Mark Driscoll's Mars Hill Church fit the definition of a cult.

"[I attended] personality-centric churches where you have a super-dynamic, charismatic, gregarious senior pastor, who is a wonderful communicator and can preach brilliant sermons…but there's nothing else really going on," said Elizabeth. "There might be programs and stuff for the kids, but it's all centered around what this celebrity, super-star pastor has to share."

Consequently, Esther found herself comforted by Catholicism's hierarchy and accountability, despite the scandals in which the church has found itself entangled over its hundreds year old history.

"Someone said to me, 'You left one cult and then joined the biggest cult of them all,'" Esther laughed. "…What I found there is [answers to questions like] do abuses happen? Obviously. Do scandals happen? Obviously. Do bad things happen? Yes."

But "when you're dealing with a large body of human beings, you need structure," continued Esther. "You report to your bishop, your bishop reports to his cardinal. There is a way to have things done and things are checked and rechecked."

Esther also believes that Catholicism takes her experience as a woman seriously, in contrast to "male dominated" Evangelical and protestant Christianity.

"There is a very practical appreciation for women in the way that the Catholic Church treats women, honors women — so many saints are women — the way it honors Mary, the mother of Jesus," said Esther, who recalls her upbringing in the Assembly as one where female dating behavior or clothing style was often monitored and controlled by the community and her voice and feelings marginalized or belittled for its leaders.

"For me that spoke of a balance of power because when we are dealing with an institution that is full of human beings, we need to hear the feminine voice of spiritually. And it can't be drowned out," she added.

Esther admits that she has not "completely worked through" her feelings on formal female leadership in the Catholic church, but that the gender restriction for priesthood is not a "deal breaker."

"Equality doesn't mean we all do the same things. I think that's the difference for me. I don't think I'm less valued because I don't do the exact same things that men do," said Esther. "I just want to see the things I do do equally valued."

Esther noted that throughout the process of crafting her memoir, she had the opportunity to share details of her life with her children and had observed her older children "coming to appreciate what my husband and I have overcome and the new life we have built for ourselves."

"I did everything in my power to remove myself from ever being associated with what happened in my church. Even to the point where I wrote under my first and middle name because I was so horrified and ashamed of what happened," said Esther. "I didn't want any association. All that to say, I really think that writing about it and what this has become was given to me….I believe that I'm whatever God wants. If there's another topic that will be given to me that I will write about it than that's what I'll do. I do know that God gave me a gift for writing and telling a story and communicating and I'll just use that however is needed."