How the faithful are partnering with developers to save affordable housing and America’s homeless

Houston’s New Hope Housing

In the city of Houston, Texas, New Hope Housing, the city’s leading provider of permanent supportive housing, was started with some $1.25 million in seed money raised by the historic Christ Church Cathedral in response to the city’s homelessness crisis in 1993.

“Really it’s the Cathedral that thought about this, thought about what they were going to do to help the homeless and near homeless,” Joy Horak-Brown, president and CEO of New Hope Housing, said in a recent interview with CP.

“It’s important to know why they struck on that as a mission and it was because all they needed to do was to walk from the cathedral downtown to the parking lot across the street. It was obvious there was a problem. There were people with no place to live, no decent place to live. It was no decent place to live or no home at all. And they decided to do something about that and they challenged the local community,” Horak-Brown said.

She explained that Christ Church Cathedral is Houston’s first religious institution and was founded when Texas was still a republic. So in 1993, when the church launched a fundraising campaign to restore its building, they decided to raise money to help the community as well.

“So for every dollar they raised for their own home, they would raise a dollar for the community. And $1.25 million of those dollars they raised for the community went to found New Hope Housing,” she said.

In addition to the funds that the church raised, additional support also came from other foundations in the community.

That funding was used to buy land on which 40 units of single room occupancy housing were built and they became the first successful single room occupancy housing in the state of Texas for people who had experienced homelessness.

“Today we have about 1,200 units of housing, we have another 170 units under construction. We’re about to break ground on 200 units and in the pipeline we have 130 more. We’re not stopping. We’re looking for land for other buildings. Soon we’ll have 10 buildings, more in the pipeline and more under construction,” Horak-Brown explained.

She said even though the idea of permanent supportive housing is relatively new to Houston compared to other parts of the country like New York City, the nature of the current housing crisis demands investment in more permanent housing.

In a recent op-ed shared with CP, Sanford W. Criner, Jr., board chair of New Hope Housing, described Houston’s current affordable housing problem as dire.

“There is a shortage of approximately 150,000 affordable units for citizens living in poverty, defined as people earning less than $32,000 for an individual and $45,000 for a family of four. And the shortage grows daily,” he wrote.

Citing 2019 research from The Kinder Institute, which does a yearly survey, he explained how housing costs have risen most quickly for Houston’s lowest-earning workers but was not much easier for the city’s population in general.

“35% struggled to pay for housing, 25% had no health insurance, 33% had difficulty paying for food, and 40% couldn’t come up with $400 for an emergency,” he wrote.

“Think about that: if 40% can’t come up with $400 for an emergency expense, what happens if they’re laid off, even briefly, or have a medical problem – or even just an automotive breakdown? We know what happens because we see it every day: they fall into homelessness, perhaps not the kind you see under our freeways or in downtown doorways, but homelessness nonetheless,” he said.

He also noted how New Hope Housing’s properties are providing a cost-efficient solution to the city’s homelessness problem and could be used as a national model in responding to the crisis.

“In 2013, the most recent year for which such statistics are available, the City of Houston estimated it was spending over $100 million a year responding to homelessness — police, incarceration, hospitals, etc. Affordable housing with support services has proven to lead to an almost 55% decline in the rate of incarceration and is much more cost-effective. And with the average visit to an emergency room — usually the only place the homeless can access medical care — running about $3,700, it becomes obvious that an apartment at a New Hope Housing property at about $6,500 a year is much more affordable,” he wrote.

He explained that the average monthly expense to house, feed and provide services to an individual in a shelter is over $2,200; for a family, as much as $12,000. Rents at New Hope Housing properties range from $550 to $850 and includes free utilities and supportive services for as long as they choose to stay.

“If you’re wondering where the money comes from to build these properties, we raise it from federal funds administered by the City of Houston (bless you City of Houston!), Low Income Housing Tax Credits, local and national philanthropic foundations, corporations — and people like, well … you. As a result, all of our properties are debt-free so we can reduce our rents to the lowest possible level. Homelessness isn’t a Houston problem, it’s a national problem, but someone must lead the nation to an enduring answer — why not Houston?” he added.

Horak-Brown said most of New Hope Housing’s inventory is dedicated to single-room occupancy, adults living alone who have extraordinarily modest incomes of $10,000 a year and below.

“People who might be a security guard, people who might be living on a small pension, veteran’s benefit, social security,” she said.

“If you never earned a large income in the first place your social security check is less than $800 a month. That’s pretty hard to live on. And so the type of housing that we offer is a perfect solution. And many of our units are dedicated to housing those who have been literally homeless. A number of our units are dedicated for the chronic homeless, that would be people who have lived on the street for at least a year,” she said.

She said in addition to other funders, a number of churches continue to support the work of New Hope Housing, which also now has a property featuring 187 one-, two- and three-bedroom apartments for formerly homeless and at-risk families.

Horak-Brown said she is happy that affordable housing and homelessness is now finally a national conversation and people are beginning to realize that “it isn’t just those people who might become homeless.”

“I believe what has given rise to it (housing problem) is the increasing cost of housing throughout the country and wages simply have not kept up. They just haven’t. There is no parallel in the rise in wages and the rise in rents, none whatsoever and that is what has led to this,” she said.

“And then, of course, the fact that we lack, as a nation, healthcare, most particularly mental healthcare. For someone who has a problem that in your family or in the families of your friends would be managed by medical intervention … isn’t managed for the poor or working families."

“That healthcare does not exist and where it does, it’s extremely expensive. And so really one of the things I’ve learned is if you become homeless and you have no mental health problem at all, just wait. Give it a little time. Living on the streets will create a mental health problem for you. Just imagine yourself living on the street when the sun goes down,” Horak-Brown said. “It’s a terrifying notion. I don’t think I would do well for very many minutes myself.”

Housing First

In an Oct. 28, 2019, letter to President Donald Trump, Democratic California Congresswoman Maxine Waters criticized the Trump administration’s approach to homelessness policy highlighted in The State of Homelessness in America report.

Waters contended in her letter to the president that it provided an “oversimplified and misleading narrative of why homelessness exists in this country and the policies that may be successful” in reducing the problem.

“For example, the report ignores years of sound research on the efficacy of the Housing First approach in favor of supporting ‘service participation requirements’ that have been proven to act as barriers to not just housing, but also employment, sobriety, higher education, and any number of positive life outcomes,” Waters argued.

Housing First is an approach to quickly and successfully connect individuals and families experiencing homelessness to permanent housing without preconditions and barriers to entry, such as sobriety, treatment or service participation requirements.

Horak-Brown also argued that she believes “there is a misunderstanding of some in government of Housing First.”

“Housing isn’t a reward for the homeless for getting a job or for having been drug-free for six months. You must place someone in housing with the services that are helping them remain sober in order for them to be successful. You can’t very well expect someone to achieve and maintain sobriety living in a tent under a freeway or sleeping in a doorway,” she said.

In Assessing the Faith-Based Response to Homelessness in America: Findings From 11 Cities, Byron R. Johnson, distinguished professor of the social sciences and director of the Institute for Studies of Religion at Baylor University, and his colleagues, William H. Wubbenhorst and Alfreda Alvarez, examined homelessness in:

Atlanta, Baltimore, Denver, Houston, Indianapolis, Jacksonville, Omaha, Phoenix, Portland, San Diego and Seattle.

The study was undertaken to provide an initial, credible estimate of the impact, socially and economically, of faith-based organizations in responding to homelessness. The study found that some 60% of the emergency shelter beds in these cities are provided through FBO homeless ministries.

In a recent interview with CP, Johnson noted that, as reflected in the Trump administration’s report on homelessness, many of these FBOs were concerned the Housing First policy doesn’t “address core problems that homeless people have.”

“In the field, when one goes out and talks to organizations, you do hear things that indicate a high level of concern about Housing First. There is this thought that it doesn’t address core problems that homeless people have. It may address the issue of giving someone an address but it doesn’t address the issue of addiction, joblessness and other kinds of problems like transportation that so many homeless people have,” Johnson said. “Wherever we would go in those 11 cities, this issue came up all the time of a general frustration that Housing First did not target the core issues that homeless people have.”

When asked about these concerns expressed by FBOs about providing housing with no pre-conditions, Horak-Brown believes there are other ways to respond.

“Make no mistake, we don’t tolerate people abusing drugs, you don’t know what your neighbors are doing behind closed doors. But if drug use (for example) comes to our attention, in one of our buildings or alcohol abuse … when those situations arise, we work with the person to get immediate intervention,” she explained.

“If they are unable or unwilling to cooperate in that effort, then we do evict them,” she said.

“We do a great deal to help people preserve their housing because preserving your housing is key to any kind of decent stable life much less to recovering … I was very reluctant to do any Housing First because I thought that I would have such problems in our building with drug and alcohol use and that we would be unable to work with people effectively to help them continue on the path that they said they want when they move into housing,” she noted. “It has worked very effectively in our housing. I cannot speak for others.”

She said she hopes more churches will begin speaking out on homelessness and housing and then taking action to help in the way Christ Church Cathedral has responded.

“I would hope that an increasing number of churches would lift their voices strongly as the Cathedral has in discussing this issue and then walk what they talk, what they say,” she said.

“I can tell you for sure and it’s always been my belief, that single-use occupancy housing for the formerly homeless and those at serious risk would have existed at some point in Texas, but it is the moral authority of the Cathedral that got it moving and it moved when it happened. And that moral authority helped bolster us, helped our growth. For many years, just about until a year and a half ago, our offices were on the Cathedral campus. And they were pro-bono beginning in 1996 until 2018,” she added.

The housing crisis in Washington, D.C.

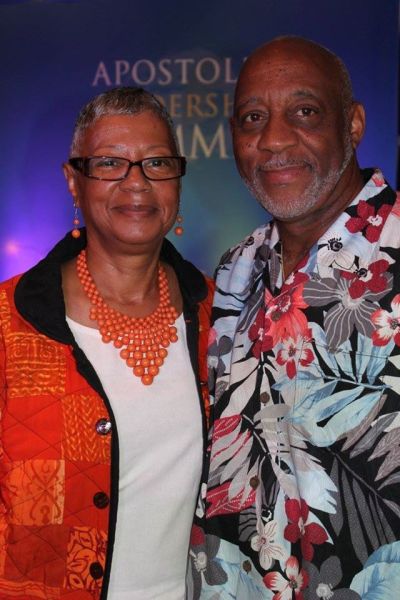

For the last 30 years, Pastor Patrice Sheppard and her husband, Eugene, have been fighting for affordable housing in Washington, D.C.

And even though she believes the district’s housing crisis has gotten worse since 1989, churches could make a bigger impact on the issue locally and nationwide if they leverage their voice and assets on the issue collectively.

“I think the key word is collectively. When we band together we’re able to do a lot more, more effectively and those that can do should do because the poor you have with you always and when you would do them good,” Sheppard told CP.

Sheppard is the executive pastor of Living Word Church, where her husband serves as senior pastor. Their ministry, she said, grew out of a desire to serve the homeless and has evolved into a multi-organization effort that has created affordable housing and other initiatives to uplift their community.

“My husband and I started working in the District of Columbia in 1989. We were going to a transitional shelter for homeless families and in the process of doing that [discovered] when a resident would get a Section 8 voucher or public housing, the contractor would then bring them back to the shelter to serve as a case manager.

“What would happen is when people made donations to the shelter, this person would take out what she wanted to have and then give the rest to the residents that were there. It became a case of the oppressed becoming the oppressor all over again,” Sheppard said. “At that point, we decided that we could do a better job in serving people who were homeless or transitioning from homelessness into housing. So we formed Lydia’s House.”

Lydia’s House is a full-service HUD-approved faith-based counseling agency and a District of Columbia-funded housing counseling agency serving Ward 8. When Sheppard and her husband first started the nonprofit, it began as an after-school operation.

“We would do after-school programs (that was in the late 80s early 90s). Public schools weren’t opening on time, we had the worst rate of children not meeting math and reading goals. It was just a mess … the crack epidemic was at its height then. So we started working with children as a way to reach the adults,” she said of the Bellevue Washington, D.C., neighborhood, which some still associate with high crime.

After a few years of doing that work, Sheppard said they began to notice a lot of abandoned and boarded up property in the community and with the help of their approximately 50-member church and a $203,000 loan, they began purchasing 4-unit apartment buildings and single-family homes and restored them for low-income families.

She explained that after the church rehabbed the homes, they kept them affordable by renting one bedrooms for between $400 and $500 dollars a month. Currently, she said, market-rate one bedrooms go for $1,500 a month, which is not affordable for many people.

“Our goal wasn’t to make the most money off the people that could least afford it. It was to change the outcomes of low and very low-income households there. You don’t get into affordable housing to make money. You get into affordable housing to serve people, which has always been the focus of what it is that we were doing,” she said.

Around 1997, Sheppard said her husband developed a vision to spur economic development in the neighborhood. So they established the Far Southwest-Southeast Community Development Corporation.

“The mission was to acquire property and develop them and create opportunities for businesses in the neighborhood,” she said.

“At that point in time, there was one of the strip malls in the neighborhood. And part of the strip mall, a movie theater, had been abandoned and boarded up for over 20 years. Then there was an independent pharmacy on the corner that had been boarded up for years. And then there was another parcel that separated those two properties,” she recalled.

“During the process, his heart was to get those properties, rehab them and bring affordable housing into play. And we went through several iterations of being able to do that. One of the things that we knew was why would a government agency work with a group that focused on children so that’s when he decided to form the community development corporation,” she said.

It was at this point in their work that they were introduced to Enterprise Community Partners, which helped her husband translate his dream into reality.

“They gave us a small loan to be able to secure the movie theater that we needed to secure. We also moved into the neighborhood,” Sheppard said.

The couple used to live in Maryland but gave up their suburban life to experience firsthand the community they were trying to serve.

She said while they were doing that work, they didn’t really know much about development. But thanks to Enterprise Community Partners, they were able to navigate the process successfully.

“I really thank God for Enterprise Community Partners and their faith-based initiative because they began to educate houses of worship and faith leaders on this whole development process, which is really important for us to do business in the marketplace," she said.

“They were a funder, they were an educator and they were an encourager. When it came time to put support behind community faith-based activity, they were right at the forefront of that happening and their faith-based initiative had monthly meetings that covered every aspect of the development process.

“I was able to become educated on the whole process … It’s really very critical for the faith-based community to understand the development process so that they can come to the table with the resources that they own.”

She said they bought property to develop close to their church so they could better monitor what the contractors were doing. They also hired people from the community and intentionally focused on attracting businesses that would uplift the community and change the perception of the area, which struggled.

They later invested in a 49-unit building with one-, two- and three-bedroom floorplans called Trinity Plaza.

“Trinity Plaza was the first housing development in our community in over 40 years and the business, of course, the dollar stores wanted to come in, the Little Caesar’s wanted to come in, all the things that catered to poverty wanted to be able to be there. But we held out and we leased the commercial property to an independent pharmacy that’s doing very well and a childcare facility that targets infants and toddlers, which is a shortage of those in that market in our community. We have the highest number of children in that age group,” Sheppard said.

“So we’re really proud of what the Lord has done there. It wasn’t us. It had to absolutely be the Lord because we’re just a small congregation. He guided us through that and we were able to form that relationship with Enterprise Community Partners,” she said.

In a 2016 review of Bellevue, The Washington Post noted the transformation in the neighborhood.

“Bellevue, in the District’s Southwest quadrant, is a quiet, modest residential community with well-kept homes beloved by longtime residents. Potted plants sit on doorsteps, flowers hang from porch awnings and mature trees bear golden red autumn leaves,” Audrey Hoffer wrote in the fall of that year.

Washington, D.C., has an initiative called the Home Purchase Assistance Program which provides interest-free loans and closing cost assistance to qualified applicants to purchase single-family houses, condominiums, or cooperative units.

As of 2019, eligible applicants can receive a maximum of $80,000 in gap financing assistance and an additional $4,000 in closing cost assistance. The HPAP 0% interest loan for borrowers with incomes below 80% of the area median income is also deferred until the property is sold, refinanced to take out equity, or is no longer their primary residence.

Moderate-income borrowers who earn between 80% and 110% AMI will also have payments deferred for five years with a 40-year principal-only repayment period.

Sheppard said the single-family homes that her church rehabbed to create low-income rentals were eventually sold to people who went through this program.

As she and members of her community have fought to add value to Bellevue, she said it is slowly becoming less affordable.

She noted that it’s only the homes that were purchased through the work of her organizations early on that are really being kept affordable.

“Now when you buy houses over [in Bellevue], they are starting at $300,000. So I think that the competition is making it even worse and with Amazon coming in, people are more tempted to develop market-rate housing … because it costs a lot to develop affordable housing. And most developers are in it for the money,” she said.

She said based on the work that her small church has done in fighting for affordable housing, she believes with the help of organizations like Enterprise Community Partners and others that understand the development process, churches can successfully leverage their assets in the arena.

“I’ve never talked to a pastor that said ‘well, I never cared about homelessness, I don’t care about people not being able to afford homes.’ I hear them saying ‘what is it that we can do to be able to put housing back on the market for low-income and very low-income households?’ So I think the church is very effective at doing that. So for every one unit that we put on, we’ve won a victory,” she said.

Sheppard said D.C.’s mayor has set a five-year goal of creating 36,000 affordable housing units.

“The churches own enough land to produce that many affordable housing units. It’s just a process that the churches have to go through depending on whether they are denominational churches or different venues,” she said.

“When we developed Trinity Plaza, we developed a list of 500 applicants for 49 units, so there is such a demand out there that churches are continuing to lead that as a process that can happen in our city,” she explained.

She further noted that even though the development process can be a challenge, it’s “extremely satisfying” when a project gets done.

“It’s extremely satisfying because I can boast in the Lord and what the Lord has done because God is going to get the glory … I am extremely excited that God used us to make a difference in the lives of people we don’t even know," she said.

“When you take people that have lived in poverty and squalor and give them the opportunity to move into a brand new building where nobody else has ever lived, where the hallways aren’t filthy, the stairwells aren’t smelling of urine, where they have parking, where they have a safe environment, the building is a secure building, you have to have a code to get in the building where you can change people’s environment, you change their mindset to let them see what is possible.

“When I was growing up, I lived in northwest D.C. My mother used to put us in her car and drive us up 16th Street NW and I asked her one time why she was doing that. She said because if you don’t see the kind of housing that you can have then we’ll never want to be able to do anything about that.

“It’s almost overwhelming when you hear of a family that has moved into Trinity Plaza and a mother saying it’s so affordable that she only has to work one job, that she can be home to put her kids through school. You hear a school teacher who rents one of the units say, 'I can walk to school and when I go to the library I see my students.'

“So it’s changing the culture of the neighborhood and it’s changing the mindset of the people that they are able to achieve these things if given the opportunity. For us, I think it’s very gratifying to start from nothing to be able to say we produced a $17 million affordable housing rental project in a community that has never seen anything like it,” she said.