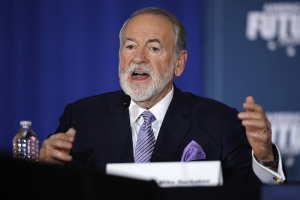

Is 'the Culture' Really the Church's Problem?

Author Ken Myers doesn't believe "the culture" is the biggest challenge facing the Church today. Rather, it's the culture in the church that's the problem as many believers live not fully transformed by the Gospel.

Myers is the founder and host of Mars Hill Audio journal, a bimonthly audio magazine featuring interviews with some of today's foremost Christian thought leaders in academics, politics, and the arts. The mission: "To assist Christians who desire to move from thoughtless consumption of contemporary culture to a vantage point of thoughtful engagement."

Myers, a former NPR reporter, is himself a thoughtful social critic who thinks deeply about the interplay between the church and the larger world. In this exclusive interview, The Christian Post asks Myers to share his views on the church today – its biggest challenges and its greatest opportunities.

CP: What is the biggest challenge facing the church today?

Myers: It's not "the culture," as we often hear, that poses the most significant challenge for the church today. It's the culture of the church.

What I mean is, we have reduced the Gospel to an abstract message of salvation that can be believed without having any necessary consequences for how we live. In contrast, the redemption announced in the Bible is clearly understood as restoring human thriving in creation.

Redemption is not just a restoration of our status before God through the life and work of Jesus Christ, but a restoration of our relationship with God as well. And our relationship with God is expressed in how we live. Salvation is about God's restoring our whole life, not just one invisible aspect of our being (our soul), but our life as lived out in the world in ways that are in keeping with how God made us. The goal of salvation is blessedness for us as human beings. In other words, we are saved so that our way of life can be fully in keeping with God's ordering of reality.

CP: Practically speaking, how has the church been too influenced by the broader culture?

Myers: Here's a small list:

- The way in which the dominant role of technology in our lives promotes the deep assumption that we can fix anything;

- The way in which proliferating mechanisms of convenience erodes the virtues of patience and longsuffering;

- The way in which the elimination of standards of public propriety and manners undermines assumptions about the legitimacy of authority and deference to the communal needs; and

- The way in which the high prestige accorded to entertainers creates the conviction that every valuable experience should be entertaining.

And this is just scratching the surface.

CP: What about the argument that church has to be "relevant" to the broader culture in order to draw seekers?

Myers: First, just to be clear about how we use the word, let's substitute the phrase "way of life" for the word "culture." How can the Church be relevant to the way of life of its neighbors? As Eugene Peterson has said, by showing a better way of life.

True seekers are looking for something different, radically different. If people are just looking for a religious band-aid or spiritual Prozac, they are not seeking the redemption promised in the Gospel, which calls them to die to self and live (really live) to Christ. If I were drowning, the most relevant reality I could long for would be someone who was a really good swimmer. If my house were on fire, I would want a man with a hose, not a lighter. If my life were plunged into darkness, light would be the most relevant thing imaginable.

Years ago I was asked about my opinion of seeker-sensitive worship services. I quipped that as long as they were part of martyr-friendly churches, they were fine. But churches that have pursued relevance by emulating fashionable cultural trends without examining the meaning of those trends – how they form the souls of those embedded in them – have not had great success in nurturing mature disciples. And remember, the Great Commission is all about making disciples, not converts. The Church should be more like a farm than a showroom.

CP: You say the church is in "cultural captivity." What do you mean by that?

Myers: One of the biggest and most consequential forms of cultural captivity of the Church is the way Christians have accepted the rise in the mid-twentieth century of what we call "youth culture," with its assumption that intergenerational discontinuity is the norm. Given the fact that culture rightly understood is an intergenerational system of communicating moral convictions, the very term "youth culture" should be seen as a contradiction in terms.

Marketers have successfully entrenched the notion of youth culture by creating product lines that are intended to define adolescent identity as a deliberate rejection of parental expectations. Not only does this age segregation weaken the family's ability to pursue the cultural task of moral transmission, it also weakens the understanding of the family itself. A proper understanding of the meaning of family is intergenerational in all directions.

The dynamics of youth culture segregate generations and extol the experience of the present at the expense of honoring the past and preparing for the future. Youth culture isn't good for culture. It is a form of disorder. And yet is a form that American churches were quick to embrace, apparently because they believed that adapting to the form of youth culture was an effective way to communicate a message of salvation. The question of whether or not it offered a good way to live life, of whether or not it was culturally healthy and sustaining, doesn't seem to have been of great concern to many Church and parachurch leaders for the past sixty years or so.

CP: How then can the church better lead its people, including its youth, in true transformation in Christ?

Myers: Eugene Peterson has written that, "It is the task of the Christian community to give witness and guidance in the living of life in a culture that is relentless in reducing, constricting, and enervating life." Rather than assuming that a way of life is OK if there's no Bible verse opposing it, we should ask, "Are we living in a way that honors as fully as possible the kinds of creatures we are and the kind of world we live in?"

First, pastors need to be committed to the long-term task of nurturing mature believers. I recommend they read books like Eugene Peterson's Practice Resurrection and Gordon Smith's Transforming Conversion, both of which deal with the often neglected but basic goal of pastoring and preaching: of bringing people to maturity in Christ. The people under their care need to understand that the goal of the Church's life is to encourage continual growth in faithfulness.

Then they should study the Church's history (especially the history of the early Church) to understand ways in which the church's shepherds have called believers to be distinctive in their way of life – not in superficial or showy ways, but from the heart of their conviction.

CP: What is greatest opportunity for the church today to truly impact the larger culture – or should we even be concerned about that?

Myers: Not long ago I interviewed a poet who suggested that he just couldn't imagine early Church leaders sitting around trying to come up with clever ideas about how they might influence Roman culture.

Robert Wilken made a very similar comment in an interview given in 1998 in which he reflected on the early Church's posture toward its cultural surroundings. Wilken pointed out that the principal way in which the early Church leaders sustained cultural influence was by discipling its members, by conveying to them that the call of the Gospel was a call to embrace a new way of life. The Church was less interested in transforming the disorders of the Roman Empire than in building "its own sense of community, and it let these communities be the leaven that would gradually transform culture."

Christians can best serve the health of American culture by striving to be deliberate about and faithful to a way of life that Church historian Robert Wilken has called the "culture of the city of God."

If congregations in America were deeply and creatively committed to nurturing the culture of the city of God in their life together, I think it would have an inexorable effect on the lives of our neighbors. But I fear that too many churches are shaping people to be what Kenda Creasy Dean calls being "Christianish" – or not deeply Christian at all. The more faithful we are in living out the ramifications of a Christian understanding of all things, the more out-of-synch we will be in American culture. But why should we wish for anything else? What can we offer the world if we are just like the world?

A new edition of Ken Myers' book "All God's Children and Blue Suede Shoes: Christians and Popular Culture" is available in print and on kindle at Amazon.com. For more information about Ken Myers and Mars Hill Audio, visit marshillaudio.org