John Brown, US Slavery and Segregated Churches: A Christian Historian Offers Perspective

NEW YORK — Martin Luther King Jr. has often been quoted as saying that he found it "shameful" and "appalling" that 11 o'clock on Sunday was the most-segregated hour of Christian America. Yet, 40 years later, many churches in the United States are still struggling to realize the dream of racial diversity in their congregations. How did the institution of slavery in America affect this trend, and what role did Christians play in U.S. slavery?

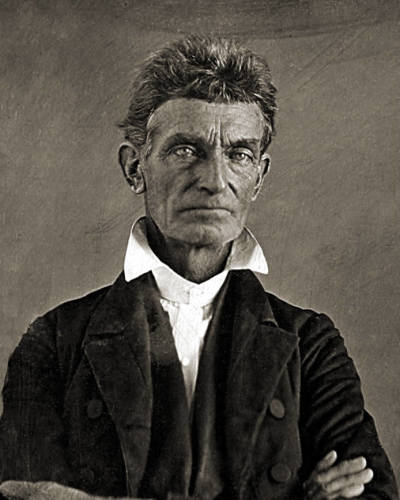

Louis DeCaro Jr., professor of Church History at Nyack College's Alliance Theological Seminary in NYC, recently spoke with The Christian Post to provide some context for these questions. DeCaro, who has pastored two multiethnic congregations, has authored biographies on Malcolm X and several works on 19th century Christian abolitionist John Brown, cast as a "radical," "insurrectionist" and "terrorist" by historians.

Brown, born in 1800 to Calvinist parents in Connecticut, believed in armed resistance to slavery. An ardent abolitionist, Brown is most known for leading less than two dozen men, including his sons, on a raid at Harpers Ferry in what is now West Virginia. Brown hoped to spark an uprising among slaves to bring an end to the institution, but failed miserably. Two days after the attack, Brown was defeated by Confederate Army Gen. Robert E. Lee, and hanged on Dec. 2, 1859, after a swift trial headed by a judge and jury who were slaveholders. During his trial, the Christian abolitionist insisted that his actions were just and sanctioned by God.

In the interivew transcript below (edited for brevity), DeCaro discusses with CP aspects of the abolitionist movement and John Brown's place in it, Christian attitudes toward slavery, and some reasons behind segregated Christian churches.

CP: John Brown believed in armed resistance to slavery. What were his convictions in joining the abolitionist movement?

LD: I think he's been often characterized maybe bit more negatively. He believed in trying to launch rescues, but he definitely believed in using arms if necessary in the event of liberating people, and he did so a number of times. He was brought up in a Christian home. His father was a convert both to Christianity and abolition in the late 18th century in Connecticut. The family migrated to Ohio in the Western Reserve...and it was really a kind of a congregational, Reformed Evangelical community predominantly, with a strong anti-slavery bent. So John was brought up in that context. He was taught that all people were made in the image of God, he was taught slavery was a sin, and he also had his own experiences [exposures to slavery].

He made a vow in his 30s that he would do something, and he felt he had a providential call, he felt vocationally that he was called to do something to end slavery. … As he matured, he was looking for opportunities. The opportunity came in 1850 with the notorious Fugitive Slave Act of 1850, which was the updated version of what the federal government had previously issued for slaveholders.

Christian abolitionists — and not all abolitionists were Christians, but the heart of abolitionism came from a Christian viewpoint. It sort of followed the different streams of evangelicalism. For instance, you had John Wesley in the 18th century whose words [were] "slavery was the sum of all villainies," so you had Methodists who were anti-slavery. You also had Calvinists who were anti-slavery from Connecticut, of which John Brown was a part.

In 1850, things started to break up because the Fugitive Slave Act was so unfair. A black person could be snatched off the streets of Manhattan or off of Brooklyn, whether or not they were a runaway. They were put into a court, not allowed to testify. The judge would be paid a greater premium for every person who was sent into slavery.

CP: In regard to John Brown, there was a particular incident he was involved in that some say was the catalyst for the Civil War.

DeCaro: That was the Harpers Ferry raid. There's other history, there's controversy around Brown, but I happen to take a position that he was a positive figure, a good figure. I know there's controversy and there's a point of extended argument, which I won't get into. In 1859 he launched what he himself saw as a grand rescue. He was going to go into Virginia, he was going to begin to gather enslaved people, move through the mountains…through the South, and try to build a community of enslaved people, Native Americans and whites. It was essentially an interracial liberation movement, fighting in defense against slaveholders.

He really expected the kind of domino effect would take place, that so many enslaved people would run away, that what it would really do is be an attack upon the economic viability of the institution of slavery. If enslaved people begin to run away and become unreachable, that's going to spread. What would happen is that the slave masters would hurriedly sell their slaves deeper south, but the farther south they would go, the more this would take place. That was (Brown's) plan. He failed right at Harpers Ferry.

CP: What about Christians who were pro-slavery? How were they involved, and what were their arguments?

DeCaro: That really comes down to biblical hermeneutics and interpretation. It's sad to say that there was — and maybe even to this day continues to be — people of a conservative Evangelical background who will argue, even if they disdain the way slavery was fleshed out, that it is a biblical institution.

The argument tended to be: "Does the Bible justify slavery?" The South had a very rigid, certainly ungracious, but also very literal interpretation of the Bible in justifying slavery. Although there were strong Evangelicals who were against slavery, many of the leading abolitionists became progressively a bit more liberal in their interpretation of the Bible in order to, I think in a sense, fight this battle.

I don't think it was necessary, because I think today we would say that there's plenty of room for exegesis that shows that slavery was not desirable, it was part of the ancient culture. We also have to recognize that the slavery of the 19th century was a race-based slavery. That's something that was not in the Bible, per se. There's a lot of other issues that impact that.

There were southern Presbyterians particularly, and the Episcopal Church, even the Roman Catholic Church in the South never challenged slavery. There were particularly some very powerful Evangelical Reformed Presbyterians in South Carolina and so forth that essentially wrote the book in defense of slavery. The Methodist Church was split because Methodists were following Wesley's anti-slavery but in the South they increasingly tolerated slavery and would not attack it.