Man Volunteers for First Human Head Transplant Neurosurgeon Calls 'HEAVEN'

A Russian man who doctors say should have been dead long ago has volunteered to become the first human head transplant patient in a groundbreaking operation one neurosurgeon calls "HEAVEN."

The Russian man, Valery Spiridonov, 31, has Werdnig-Hoffmann disease, "a genetic disorder that wastes away muscles and kills motor neurons — nerve cells in the brain and spinal cord that help move the body," according to The Atlantic magazine.

"He has no memory of ever walking, and his movement today is limited to feeding himself, typing, steering his wheelchair with a joystick, and little else. He sits with his right leg perpetually crossed over his left, and his body below the neck looks shrunken, almost deflated. His condition is fatal, but there's no telling how much time he has left — according to doctors, he should have died long ago," explained writer Sam Kean in a feature on Spiridonov, appearing in the September issue of the magazine.

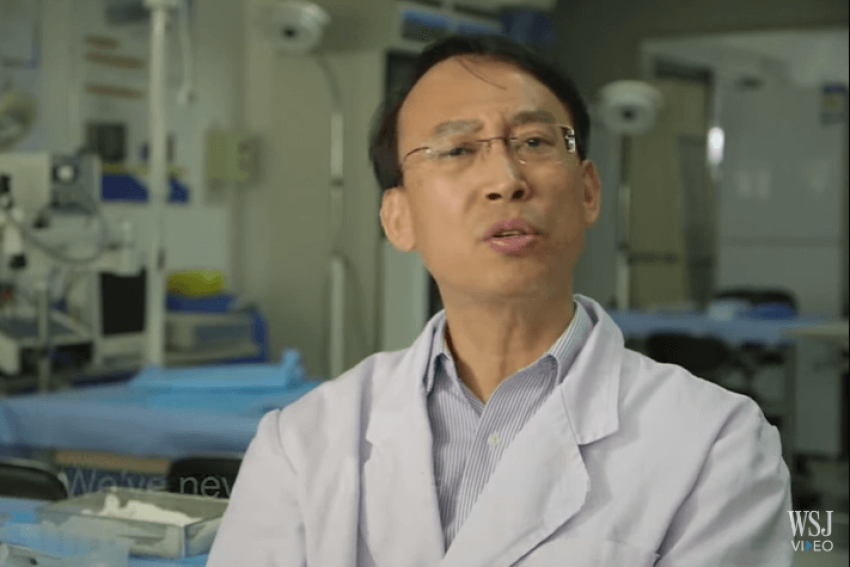

Two doctors, a surgeon in Harbin, China, named Xiaoping Ren and a neurosurgeon from Turin, Italy, named Sergio Canavero are planning to lead a team of 80 surgeons to help Spiridonov achieve his dream of a new body as early as 2017 and the procedure could cost up to $100 million depending on where it happens.

Canavero "sees head transplants as a step toward radical life extension for all human beings. Indeed, he nicknamed the surgery the 'head anastomosis venture,' or HEAVEN, with a nod toward death and resurrection," explains The Atlantic.

He first announced the idea to attempt a human head transplant in 2013 and began floating it to other like-minded scientists, including Ren. And it was some time during this promotion period that he was contacted by Spiridonov to be a part of what some scientists and ethicists have dismissed as risky "junk science" that could result in Spiridonov's death.

And this is what The Atlantic describes will happen if everything goes according to theory.

James Giordano, a neuroscientist and neuroethicist at Georgetown University, told The Atlantic that he doesn't think the head-transplant surgery will succeed but suggests that critics consider the historical context of the procedure.

"I see this as being representative of much of the trajectory of very rapid experimental medicine," he said. "There are those who look at this and say, 'This is cowboy medicine. This is Wild West. This is so avant-garde. This is so bizarre.' No. It's really not that bizarre," he said.

At one point in history medical procedures like heart, kidney and face transplants seemed bizarre.

"This is something we've been flirting with for a long time," said Giordano.

The Georgetown neuroethicist also noted that Spiridonov has no other treatment options and has given informed consent to the operation.

"One could look at this patient in two ways," Giordano said: "as an idiot or as an astronaut," Giordano said.

Dr. David Stevens, CEO of the Christian Medical & Dental Associations has a different opinion. He called the planned head transplant unethical in an interview with The Christian Post in June.

"Believing in the sanctity of life from a biblical point of view, how do you ethically do this?" he asked pointing out that the "risk to the patient is just enormous."

"There's no way to ethically do this type of experiment when you haven't proven it in the lab. What happens when it doesn't work? Patient's head has been severed and they're going to die," he continued.

Stevens also questioned whether volunteers for the surgery can give "true informed consent," given their likely mindset.

"I am sure there are exceptions to the rule, but people often go through a time of depression and suicidal ideation and all sorts of things after a major accident that makes them quadriplegic," Stevens said.

"And so, it's very easy to prey on people who are desperate for some sort of hope, some sort of cure. I would very much be concerned about getting true informed consent from a patient."

Assya Pascalev, a philosophy professor and bioethicist at Howard University who studies organ transplants raised concern about consent to the surgery as well.

"Just because somebody consents to harm, that doesn't necessarily give a physician the right to harm the individual," she said. "My consent to slavery doesn't allow you to enslave me."

Spiridonov, a tech geek who runs an educational-software company from his home in Vladimir, 120 miles east of Moscow however, isn't too worried about the risks he will face.

"For me, a body is like a machine, doing some duties or some regular stuff, just to support living," he told The Atlantic. The transplant he said "is not about philosophy; it's about mechanics."

He is also well-aware of the risks involved with his decision and can change his mind at any time.

China, where Ren is based, is yet to approve the surgery.

When Canavero first announced his plan, he said the surgery would take place in late 2017, probably in China, but he has since revised that timeline to say it could be done within two years of government approval once the team has the funding to do the procedure.

The surgery is expected to cost between $10-$100 million depending on where in the world it takes place explains The Atlantic and Spiridonov and the team of surgeons are still trying to raise the money.

The Russian government has not agreed to pay for the experimental surgery, so Spiridonov is seeking donations and selling hats, mugs, T-shirts, and iPhone covers online to raise money explains The Atlantic.

Canavero is also hoping to partner with researchers in the U.S. to win a $100 million grant from the MacArthur Foundation.

If that fails, he told The Atlantic, he plans on asking tech billionaires like Mark Zuckerberg to "fork over the bread" for the surgery.

If Spiridonov does not get the funding needed to do the surgery, says Ren, he could lose his place in the line of 10 prospective patients who have come forward to try the surgery.

For now though, Spiridonov dreams of one day riding a black 156-horsepower sport bike. And he imagines himself "cruising up the coast of California or Italy—riding tall in the seat instead of sagging low, the way he does now in his wheelchair."

"I believe I will like this experience," he said.

READ MORE IN THE ATLANTIC.