Mark Sanford v Elizabeth Colbert Busch: A Very Special Election in South Carolina

A former Republican governor of a deeply Republican state is running for a deeply Republican U.S. House seat, but he is best known for claiming to be walking the Appalachian Trail while he was actually visiting his mistress in Argentina, and he has a court date two days after next Tuesday's special election because he allegedly trespassed on his ex-wife's property. His Democratic opponent has never run for office and would be totally unknown, except that her brother is one of the nation's most popular comedians.

They aren't called special elections for nothing.

The circumstances in the race for South Carolina's 1st District between ex-Gov. Mark Sanford (R) and Elizabeth Colbert Busch (D), sister of comedian Stephen Colbert, are so odd that the result, no matter what it is, won't have much predictive value for next year's midterm. What future race will look like this? But that's just the thing with special elections: They are all unique in some way, because they are generally not waged on regular election days, they generally have poor turnout, and they come about because the previous occupant of the office either died in office or resigned, oftentimes under duress. No wonder why the Crystal Ball's Alan Abramowitz has found that "the results of special congressional elections do not accurately predict the results of the subsequent general election."

Kooky circumstances are common in specials, and they can help create strange upsets. Nearly two years ago, the national political world was transfixed on another special election, this time in Western New York's 26th District, where Rep. Chris Lee (R) resigned after the married man was found flirting on the internet. The district had gone 52%-46% for John McCain in the 2008 presidential race, yet Kathy Hochul (D) was able to win a three-way race, and her messaging on Rep. Paul Ryan's (R) budget plan was largely credited as the reason. In hindsight, the Ryan budget probably wasn't as big of a factor as Hochul's personal political abilities, combined with the incompetence of Republican nominee Jane Corwin and the disruption from self-described "Tea Party" nominee Jack Davis, whose presence on the ballot — despite not being all that "Tea Party" at all because of his economic protectionism and pro-choice abortion views — might have made the difference in the race.

Again, the word special works well to describe that race, too.

In this latest special election, Gov. Nikki Haley's (R) appointment of then-Rep. Tim Scott (R) to the Senate opened South Carolina's 1st District, which contains part of Charleston while running south to Hilton Head along the Palmetto State's Atlantic coastline. Sanford, who previously held the seat before being elected in 2002 to the first of his two terms as governor, was one of 16 candidates in the special election Republican primary field (Colbert Busch faced only a single, minor challenger). Curtis Bostic, a former Charleston County councilman, finished second to Sanford in the primary and advanced to a runoff. The field — 15 challengers aiming for second place against a former governor — and the calendar — the runoff was held just two weeks after the March 19 primary — conspired against Sanford's challengers.

After the runoff, reports surfaced of Sanford's trespassing incident, which led the National Republican Congressional Committee to make a shrewd decision to declare that it would not be spending money on the race. Even if they lose this seat, the Republicans will still have a 232-202 advantage in the House (with one opening in Missouri that Republicans look certain to hold in a June special). They would have many months to find a candidate better than Sanford to challenge Colbert Busch in 2014, and they wouldn't have to deal with Sanford in Congress, which would be a blessing for a party that has such well-documented troubles with women voters. All that said, it is reasonable to question how Republicans let Sanford become the nominee; perhaps it couldn't have been helped, but if Karl Rove and his allies are really determined to prevent the next Todd Akin or Richard Mourdock from kicking away a race, wouldn't SC-1 have been a good place to start? Still, Sanford is not without his supporters: Haley still backs him, as do Sens. Lindsey Graham (R-SC) and Rand Paul (R-KY), and the conservative group FreedomWorks. Plus, Sanford's philandering has earned him another high-profile supporter: Hustler founder Larry Flynt! "Sanford's open embrace of his mistress in the name of love, breaking his sacred marriage vows, was an act of bravery that has drawn my support," he said. Somehow we don't think this is what Republicans have in mind when they talk about expanding the base.

The Democratic Congressional Campaign Committee, among other Democrat-supporting groups, has spent close to half a million dollars on this race, which is a decision that's hard to nitpick: There's an opportunity to win a seat Democrats have no business holding. Just don't believe them when they inevitably argue that a victory, which would be the result of unique, bizarre circumstances, has broader meaning for the 2014 midterms.

Despite Sanford's troubles and the intervention of the outside Democratic groups, we are calling SC-1 a "toss-up" for now. Our sources tell us that this race is very close, and this is a very Republican seat: In 2012, Mitt Romney won it 58%-40% — that's six points better than John McCain did in the aforementioned NY-26 district when that seat was contested in 2011. If Colbert Busch were elected, the Democrats would hold only three seats where Romney did better: NC-7 (Rep. Mike McIntyre); UT-4 (Rep. Jim Matheson); and WV-3 (Rep. Nick Rahall). Put another way, our current Crystal Ball House ratings list 40 potentially competitive Republican-held seats that Democrats might target. In only three of those districts did Romney do better than he performed in SC-1: Those are WV-2, which Rep. Shelley Moore Capito (R) is leaving to run for the Senate; AR-4, which freshman Rep. Tom Cotton (R) very well may vacate to also run for the Senate; and TN-4, where Rep. Scott DesJarlais' (R) personal problems may actually be worse than Sanford's (he very well could lose his primary, which would return the seat to the "safe Republican" category). Because Democrats are at an inherent disadvantage in the House — President Obama only won 209 of 435 House districts — they need to expand the map into some heavily Republican places. The Palmetto State's 1st District would certainly qualify, though whether a victorious Colbert Busch could hold it is very much an open question.

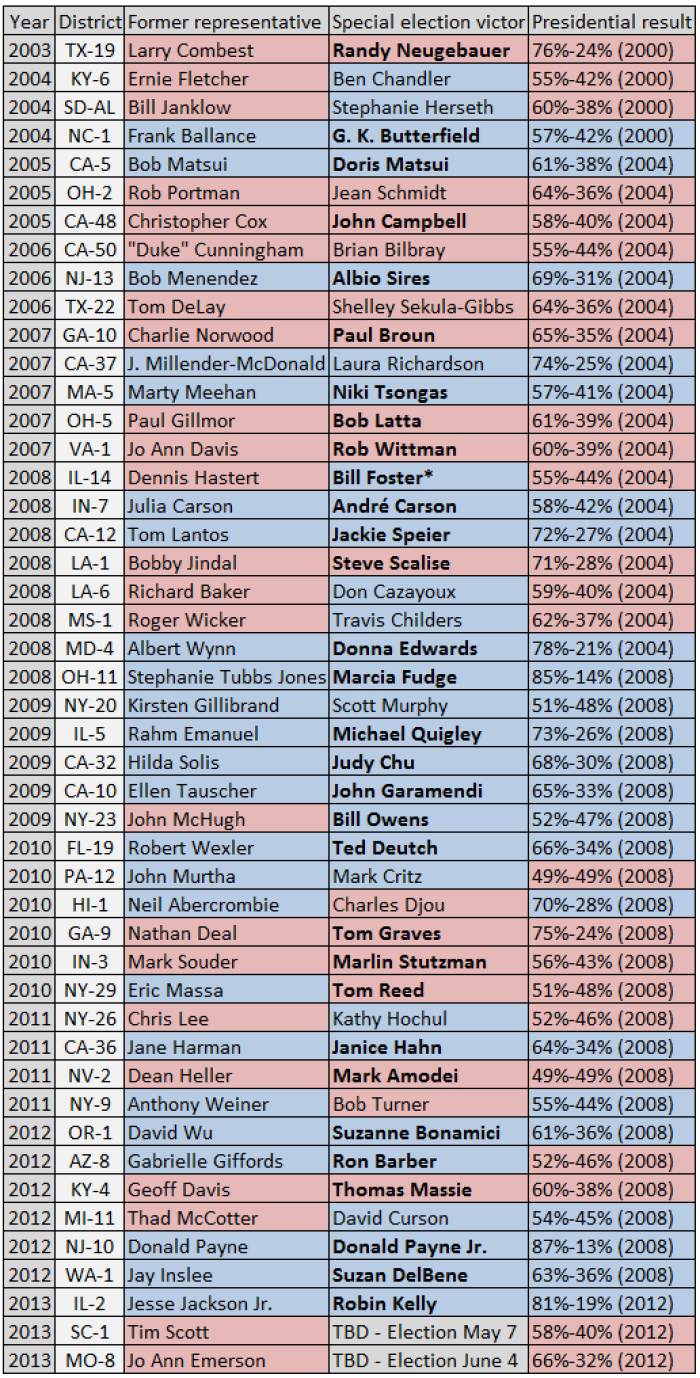

Chart 1 shows every House special election held in the last decade (going back to April 2003). In the 45 races held in that time period (not including the SC-1 special or the upcoming June special in MO-8), the party of the seat's former occupant held the seat 76% of the time.

Chart 1: U.S House special elections, April 2003 to present

Notes: Names in bold are still serving in Congress. *Foster was elected to IL-14 in March 2008 in a special election, and then he won a full term in November 2008. Foster then lost to Rep. Randy Hultgren (R) in 2010, but he came back in 2012 to defeat Rep. Judy Biggert (R) in IL-11. Additionally, President Obama's nomination of Rep. Mel Watt (D-NC) to head the Federal Housing Finance Agency could lead to a special election in Watt's heavily Democratic district if Watt is confirmed for the post.

Source: For district-level presidential results, The Almanac of American Politics 2002, 2004, 2006, 2008, 2010 and 2012, and Daily Kos Elections; for a history of House vacancies and special elections, history.house.gov.

Of those 34 races where there was no change in parties, a few races stand out, but not necessarily for the reasons that they did at the time. For instance, the OH-2 special election from August 2005 — Sen. Rob Portman's (R-OH) old seat — between Republican Jean Schmidt and Democrat Paul Hackett was often cited as a tea leaf indicating the weakness of Republicans heading into the 2006 midterms. In a sense, it was: Hackett came within three points of defeating Schmidt in a district George W. Bush won a year earlier by 28 points. But Hackett, an Iraq combat veteran, was also an unusually strong candidate — and Schmidt was an unusually poor candidate who struggled in future elections before finally losing in a primary to now-Rep. Brad Wenstrup (R) last year. Again, the circumstances on the ground — and not just the national atmospherics — were special.

In the 11 seats where there was a party change, the glory of victory has oftentimes been fleeting. In 2011, Bob Turner (R) won the right to replace ex-Rep. Anthony Weiner (D-Twitter) in a New York City seat where Obama had won 55% of the vote in 2008; the late ex-New York City Mayor Ed Koch (D) endorsed Turner in the race as a way to urge a protest vote against Obama's Middle East policies, which was seen as particularly potent in a district with a significant Jewish population. But a few months after Turner's victory, his district was carved up in redistricting. Turner ran for New York's Republican Senate nomination, which he lost, and Koch endorsed Obama for reelection soon after the special House election. Meanwhile, Hochul, the Democratic winner in the ballyhooed NY-26 special from two years ago, saw her district become even more Republican in redistricting, and she lost a spirited and close reelection bid to now-Rep. Chris Collins (R-NY) last November.

Of the 45 special House election victors over the past decade, only four won in districts where the opposite party's presidential candidate did better in the previous presidential election than Romney's 58%-40% victory in SC-1. None of them remain in Congress. In 2004, Stephanie Herseth Sandlin (D) won South Dakota's lone House seat, which she held until losing in the 2010 wave (she is considering running for the Senate or the House this cycle). In 2008, Don Cazayoux (D) won a special election in Louisiana but then lost it in the regular election later that year; the same year, Travis Childers (D) won another heavily Republican seat in Mississippi, and he held on until 2010. That same year, Charles Djou (R) took advantage of a split field to improbably win a seat in Hawaii, although he lost it in the regular election in November 2010.

This is a long way of saying that if she wins, Colbert Busch will have to hang on for dear life; in fact, she would be the most vulnerable Democratic incumbent in the country.

But Colbert Busch and the Democrats will cross that bridge if they get to it. First they need to win what would be just the latest fluky — and probably unsustainable — victory in a special election for the U.S. House.

This column originally appeared at centerforpolitics.org.