Martin Luther King Jr's 'I Have a Dream' Speech Turns 50; Surprising Facts About MLK's Historic Remarks

As the nation commemorates this week the 50th anniversary of civil rights icon the Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr.'s "I Have a Dream" speech, some Americans might be surprised to learn that Dr. King was unaware that his remarks were being recorded, and later to be sold against his will. In addition, the phrase "I have a dream" was never originally a part of King's prepared remarks.

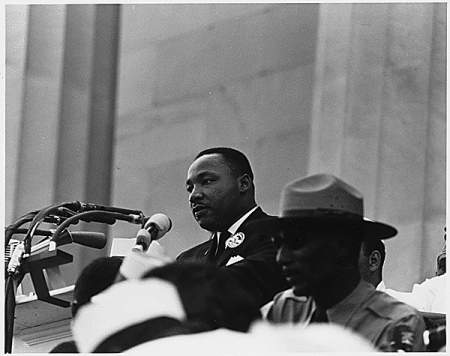

King delivered his remarks on Aug. 28, 1963, to a crowd of more than 250,000 people who had gathered with some of the country's most well-known civil rights proponents at the Lincoln Memorial in Washington, D.C. — a gathering which King predicted at the time would "go down in history as the greatest demonstration for freedom in the history of our nation." However, it was King's speech that became the centerpiece of the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom that had brought so many civil rights supporters together.

Little did King know, however, that his spirit-stirring and conscience-pricking call to "let freedom ring" would be recorded by Mister Maestro, Inc. and Twentieth Century-Fox Record Company and offered for sale. Although a federal case was opened with the Baptist minister and his attorneys claiming copyright infringement over his "I Have a Dream" speech, King and Twentieth Century Fox eventually worked out a deal that benefited various civil rights groups. The speech remains as a transcript logged as evidence among Federal documents.

Motown Records also found itself the target of a lawsuit by King, who made similar claims against the label founder's use of his "I Have a Dream" speech on three unauthorized records. King eventually dropped his suit against Berry Gordy's Motown, which went on to feature the entire speech on its Great March to Washington album.

The speech, calling for equality among the races and fair treatment of the nation's African Americans, only later came to be dubbed the "I Have a Dream" speech. In fact, according to Clarence B. Jones, a speechwriter for Dr. King, that well-known phrase was never included in the written remarks.

Jones also served as MLK's attorney and close confidant. He released in 2011 a book titled Behind the Dream: The Making of the Speech that Transformed a Nation. According to Jones, "I have a dream" was a phrase previously used by King during other public speaking engagements, and it had never quite caught on.

It was during the March on Washington that King was apparently compelled by gospel singer Mahalia Jackson, who had performed "How I Got Over" at the event, to re-introduce the phrase.

"Tell 'em about the dream, Martin, tell 'em about the dream!" Jackson yelled, according to Jones, who helped write the "I Have a Dream" speech.

That was when King reportedly nodded in Jackson's direction and moved the papers with this speech to the side, and began to ad lib...and began to preach.

"He moves the text of the speech to the left side of the lectern, grabs the lectern, looks out on those more than 250,000 people assembled and thereafter begins to speak completely spontaneously and extemporaneously," Jones told Reuters. "Everything thereafter was spontaneous," he said. "That was the 'I have a dream' speech."

MLK began several of his statements during the speech with "I have a dream," as an excerpt of the speech shows (parenthetical words were made by others picked up in the recording).

I have a dream that one day (Yes) this nation will rise up and live out the true meaning of its creed: "We hold these truths to be self-evident that all men are created equal." (Yes) [applause]

I have a dream that one day on the red hills of Georgia the sons of former slaves and the sons of former slave owners will be able to sit down together at the table of brotherhood.

I have a dream that one day even the state of Mississippi, a state sweltering with the heat of injustice (Well), sweltering with the heat of oppression, will be transformed into an oasis of freedom and justice.

I have a dream (Well) [applause] that my four little children will one day live in a nation where they will not be judged by the color of their skin but by the content of their character. (My Lord) I have a dream today. [applause]

I have a dream that one day down in Alabama, with its vicious racists, with its governor having his lips dripping with the words of "interposition" and "nullification" (Yes), one day right down in Alabama little black boys and black girls will be able to join hands with little white boys and white girls as sisters and brothers. I have a dream today. [applause]

I have a dream that one day "every valley shall be exalted (Yes), every hill and mountain shall be made low; the rough places will be made plain and the crooked places will be made straight (Yes) and the glory of the Lord shall be revealed, and all flesh shall see it together." (Yes)

In addition to referencing Scripture (such as Psalm 30:5 and Isaiah 40:4-5), King opened his remarks by pointing to Abraham Lincoln's Gettysburg Address, and went on to allude to the Emancipation Proclamation, Declaration of Independence and the U.S. Constitution. The well-read orator was said to have even adapted a phrase from William Shakespeare's Richard III for his historic speech.

Although "I Have a Dream" was celebrated by the public and covered widely by the press the day following the March on Washington, The Washington Post's Robert G. Kaiser recalled that the publication embarrassed itself by severely underestimating the speech's impact. In fact, the publication's lead story the day following the March on Washington neither noted King's name nor his speech.

Kaiser, who previously served as the Post's managing editor and was a summer intern at the time of King's historic speech, lamented in a recent op-ed, "I've never seen anyone call us on this bit of journalistic malpractice. Perhaps this anniversary provides a good moment to cop a plea. We blew it."

King, who was assassinated five years after the March on Washington at the age of 39, concluded his "I Have a Dream" speech with a call to "let freedom ring."

"And when this happens, and when we allow freedom to ring," said King, "when we let it ring from every village and every hamlet, from every state and every city, we will be able to speed up that day when all of God's children, black men and white men, Jews and Gentiles, Protestants and Catholics, will be able to join hands and sing in the words of the old Negro spiritual: Free at last! Free at last! Thank God Almighty, we are free at last."

Watch a recording of Martin Luther King's "I Have a Dream" speech from Aug. 28, 1963, below: