New Netflix series shows how Christian pharmacist took down deadly opioid 'pill mill'

Warning: This article contains spoilers

A new four-episode Netflix docuseries highlights the story of a Christian pharmacist in New Orleans suburb who turned the grief from his son’s death into a determination to shut down a doctor he believed was fraudulently prescribing painkillers to thousands in his community.

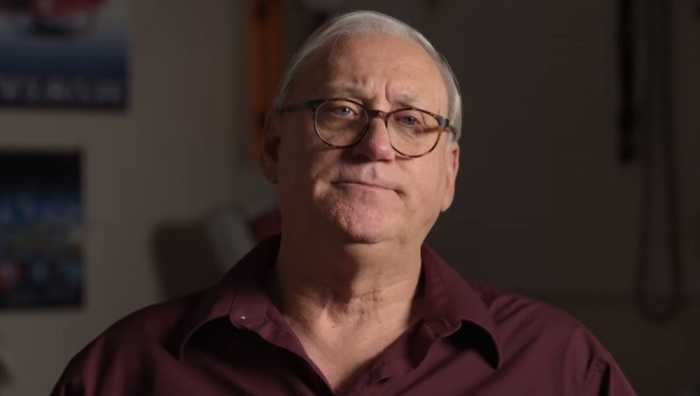

The online streaming platform released the new series, “The Pharmacist,” last week. The program centers on the efforts of Dan Schneider, who worked for years at a local pharmacy in St. Bernard’s Parish, an upper-middle-class community located adjacent to New Orleans’ Lower Ninth Ward.

The Lower Ninth Ward had developed a reputation through the decades for crime and drug addiction. It was a community plagued by the crack epidemic during the 1980s and 1990s.

In 1999, Schneider’s son, Danny Jr., was shot to death during what was believed to be a drug deal gone bad in the Lower Ninth Ward. With so many killings happening in the Lower Ninth Ward at the time, Schneider was not pleased that authorities were not able to find and hold accountable his son’s killer.

As Schneider took time off from his job to run his own investigation into his son’s murder, the entire first episode was devoted to his months-long quest to find out who killed his son. Schneider canvassed the streets looking for clues. Thanks to a courageous witness who faced death threats and had to flee her hometown, a teenager named Jeffery Hall was identified and eventually sentenced to prison for the crime.

After Schneider returned to work at the pharmacy following Hall’s conviction, he noticed a high number of teenagers about his son’s age coming in with prescriptions for OxyContin.

Produced by Purdue Pharma, the pill was billed at the time as somewhat of a revolutionary pain medication that was supposed to have a lower risk of addiction. However, the people he noticed coming into this pharmacy to fill the prescriptions showed no signs of obvious pain that would warrant such pain medication.

Schneider would often ask questions of the customers to figure out what their need for the medication was and consulted many of them not to take the medication.

Schneider began to notice a troubling pattern as he looked through the records at his pharmacy — most of the prescriptions the store was filling were for pain medications being prescribed by the same doctor. That doctor is Dr. Jacqueline Cleggett.

What Schneider was noticing was the beginning of the nation’s opioid epidemic in his community. Being that many of those filling prescriptions were his son’s age, he saw his son’s spirit in them. He wanted to do something and he did.

“I want to do something for my son and myself. I want a calling and I believe I may have a special calling, because I also, God, have given my only son,” Schneider said in the docuseries.

“And I want to give him purpose on Earth, as it is in Heaven. He became a martyr — I don't know if that's the right word — but he may save some of these other kids' lives. And again, maybe that's my mission.”

Schneider notified the Federal Bureau of Investigation and the Drug Enforcement Agency about his concern about Cleggett.

However, Schneider received little information from either agency about what the federal government was doing to investigate the matter. Therefore, Schneider launched his own investigation with the help of a former patient of Cleggett’s who used to fill prescriptions at his pharmacy.

According to a former patient interviewed in the documentary, Cleggett would usually prescribe him three drugs: Oxycontin, Soma and Xanax. Those three drugs are referred to as the “Holy Trinity.”

Cleggett was selling prescriptions for cash and would see a staggering 76 patients per day on average, according to a DEA investigator interviewed for the series. Seventy-six is far more patients than an average doctor can consult in a day if they are doing a serious consultation.

Cleggett’s operation was described in the docuseries as a “pill mill,” a term to describe doctors who open medical clinics to sell prescriptions for OxyContin, Soma and Xanax.

Schneider continued to grow troubled that federal authorities were taking so long on their investigation into Cleggett’s practice. He grew conflicted even more when he began to read or hear in the news about how people his pharmacy was filling prescriptions for were dying of overdoses.

Schneider heard about how one doctor in Ohio was prosecuted for writing 4,000 fraudulent prescriptions. Knowing that Cleggett had prescribed far more than 4,000 prescriptions, Schneider was advised by a local prosecutor in Ohio to voice a complaint with the local medical board.

He was hoping to get “smoking gun” proof at his work at Bradley’s Pharmacy.

The “smoking gun” turned out to be a mother and her small daughter who came into the pharmacy with high-dose prescriptions for OxyContin, Valium, Soma and Roxicodone. Those drugs were alleged to help the 100-pound child deal with pain from Sickle Cell Anemia.

However, Schneider said that such a high dose of those medications could have killed the girl.

After they left, Schneider called Cleggett’s office and asked Cleggett directly if she issued the prescription. She confirmed that she did. When Schneider pressed her on the danger of the child taking such medication, Schneider said that Cleggett told him: “Who the f*** made you a doctor?”

He eventually spoke with the young girl’s physician who treated her for the illness. The doctor told him that he only prescribed the child Tylenol for the pain.

Schneider then filed an affidavit with the local medical board, which then suspended Cleggett’s license and halted her practice.

“As a pharmacist, I felt it was my mission to make a difference,” Schneider said.

An investigation uncovered that Cleggett had prescribed as many as 180,000 OxyContin pills in just one year across only 10 pharmacies.

Although Cleggett faced the possibility of 20 years in prison and 37 counts of conspiracy to distribute controlled substances for no medical purpose, she was involved in a terrible car wreck that left her with two brain hemorrhages and five skull fractures.

Cleggett accepted a plea deal in which she was convicted of one count of conspiracy to prescribe a controlled substance without a legitimate medical purpose. Because of her medical condition, Cleggett was spared jail time and sentenced to three years probation.

“I pleaded guilty to one count even though I knew that I had not done what they stated I had done,” Cleggett, who was also accused of abusing prescriptions herself, said in the docuseries.

Cleggett was one of the first pill mill doctors in the U.S. to be shut down and prosecuted. She was followed by many more across the nation as the opioid crisis took a grip.

“After Dr. Cleggett got shut down I felt like I had accomplished my mission,” Schneider said. “And I thought that might be the end of this. That wasn't the end. That was the beginning. It was like a cancer. It metastasized.”

With Cleggett out of business, more than 60 other pain clinics popped up in New Orleans and fatal overdoses doubled in St. Bernard Parish.

Schneider continued to do his best to make a difference in this community by pushing legislators to do something to tackle the crisis. He also advocated for a prescription monitoring program, which made it easier to prosecute doctors.

“I not only wanted to change St. Bernard, but I also wanted to change the country,” he said.

“I felt God wanted me to do something beyond Cleggett.”

In 2007, Purdue Pharma was convicted of misrepresenting the addictive potential of OxyContin. The company’s marketing of the pill was said to be “deceptive and criminal.” Although Purdue Pharma was forced to pay $600 million in fines, the company continued to push the product.

As the company faces thousands of lawsuits claiming that the company misled doctors about OxyContin, Purdue Pharma filed for bankruptcy last September.

Follow Samuel Smith on Twitter: @IamSamSmith

or Facebook: SamuelSmithCP