NIH Director Francis Collins details his path to Christ after living as an atheist

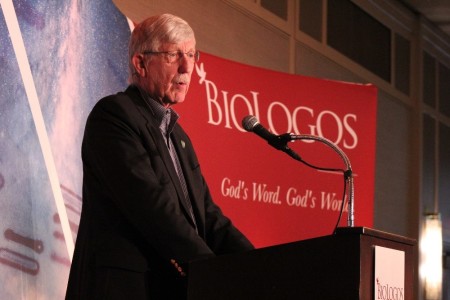

BALTIMORE — National Institutes of Health Director and world-renowned biologist Francis Collins shared the long process of how he was led to faith in Christ after an encounter with a terminally-ill patient left him pondering one of life’s great existential questions.

Collins, a 68-year-old evangelical geneticist who is credited with discovering genes associated with a number of diseases and is the founder of the Human Genome Project, took off his federal government hat this week to take part in a conference hosted by an organization he founded over a decade ago.

Collins spoke to over 300 pastors, scientists and scholars gathered at the Hyatt Regency in Baltimore’s Inner Harbor for BioLogos 2019, a two-and-a-half day conference hosted by the BioLogos Foundation, which exists to show that faith and science are not in conflict through the advocacy of Evolutionary Creationism viewpoints on origins.

The conference celebrated the 10-year anniversary of the first BioLogos conference and the launch of the organization’s website, which has served as an online resource for many pondering questions around the intersection of faith and science.

Shortly after launching BioLogos, Collins stepped away when he was asked by former President Barack Obama to serve as the head of the U.S. agency primarily responsible for biomedical and public health research.

On Wednesday evening, Collins gave a 20-minute speech detailing how he was led from a life of atheism to a walk with Christ by confirming God’s truths in the physical and scientific realities presented throughout the world.

While many Christian scientists wrestle with how they can bridge what they have learned in their fields with their faiths, Collins says that his faith has never come into conflict.

“More than ever, the world needs to hear the synthesis of science and faith is possible, not just forcing it and saying, 'This will have to do,’” Collins explained. “It is joyful. It is an opportunity for worship. I didn't always know that.”

Collins then told the crowd that he couldn’t believe that he was standing before them speaking at the BioLogos conference when reflecting back on who he was at the age of 21 or 22, as a graduate student in physical chemistry at Yale University.

At that point in Collins’ life, he had adopted a sense of “metaphysical naturalism,” what he called a “reductionist attitude” or the belief that “nothing really matters except what can be measured through science.”

Collins believed at the time that faith was basically a superstition left over from an earlier age that should be shrugged off to “move forward.”

He explained that this belief partly came from the fact that he was raised in a home where faith was not considered overly important.

“[I]t was convenient to assume there was not a God,” he said. “By the time I was a graduate student, I was an atheist. It was not a particularly well-thought through position. But it was my position and it is not so different, I suspect, than many others around me at that time or ones that we would find today in a university undergraduate dormitory or graduate classroom.”

Although he loved second-order differential equations, Collins eventually felt compelled to switch studies and apply to medical school in order to learn about the science of the human body. He was accepted at the University of North Carolina.

While at UNC, Collins said he maintained his atheism. However, he recalled that there were Christian medical students who would invite him to come sit with them at lunch. He explained that he tried to avoid them as much as he could because he thought they were “weird.”

But over the course of his time in medical school, the experiences he was having began to change. It was no longer just an intellectual exercise to think about life and death.

“Because as a third-year medical student, one is then put into the clinical experiences of sitting at the bedside of people that have terrible diseases, most of which at that point we really didn't have answers or our answers were pretty incomplete,” Collins said. “That began to trouble me because I saw in their eyes what someday might be my circumstance.”

Collins said he would wonder how he would handle the situation if it were him in the hospital bed with an incurable, fatal disease.

“I watched how they handled it, these good North Carolina people,” he said. “Many of them seemed quite at peace. They talked about their faith. I thought, 'Why aren't you angry at God? Why don't you shake your fist at what God has done to you?' But that is not what happened. They were at peace. They felt like God had been good to them and they had been blessed and they look forward to what came after.”

At the age of 26, Collins said there was one elderly female patient he looked after who suffered awful chest pains because of severe cardiac disease. During her episodes of chest pain, he said she would pray and seem at peace. Collins said she would share her faith with him regularly and that made him uncomfortable.

“But one day, she made me really uncomfortable because she told me, 'Doctor, I have shared my faith with you and you seem to be somebody who cares for me. What do you believe doctor?'” Collins shared. “I don't think anybody in an honest, open way had really ever asked me that question. I realized I was utterly lacking a response.”

Collins said he felt like he had neglected the most important question that any of us ever really asked: “Is there a God and does that God care about me?”

“At that point, 26 years, I had managed to set that aside in the pursuit of other issues. And I was supposed to be a scientist,” he said. “It was interesting finding answers and collecting evidence to see what those answers should be. I had never spent more than five minutes thinking about this particular question or what the answer might be. That really bothered me.”

Collins tried to sure up his atheism and figured it would be good to ask believers why they believe. As it turned out, some of his co-workers were Christian. He figured that they “must have been brainwashed as children and never really quite able to get over it.”

But when Collins spoke with them, he said that they actually made a “fair amount of sense.” However, he was still not fully understanding.

Collins then met with a Methodist pastor who lived on his street. After listening to Collins’ questions, the pastor gave Collins a book by C.S. Lewis and told him that Lewis had many of the same questions that he did.

“[Lewis was an] Oxford scholar who had asked those questions, who had traveled the same path from atheism to belief, kicking and screaming the whole way,” Collins said. “As I turned the pages of that book, I realized my arguments against faith were those of a schoolboy. I realized I had a lot of work to do to try to come to grips with the answer to that question: ‘Is there a God and does He care about me?’”

It still took Collins another two years before he came to have a relationship with Christ. He stressed that it was a struggle as he tried to make sense of other world religions to see which one made the most sense.

Ultimately, he said, it was through talking with Christians with a better depth of understanding and people of other faiths that he was able to come to faith.

“But I also began to appreciate that even from the area of science that I was most comfortable in, there were a lot of pointers to God,” Collins added. “It was the fact that there is something instead of nothing. … The fact that the universe seems to be fine-tuned to make complexity possible and therefore life possible. That actually, nature follows these elegant mathematical rules of second-order differential equations that I had so loved. Why should that be? Why should nature be like this?

"It seems like there should be a mathematician and a physicist behind all this. Oh my gosh, that sounds like God.”

Collins still had questions about who the Creator was and why the Creator would have such a deep love for human beings. Collins said he referred back to Lewis's book, Right and Wrong as a Clue to the Meaning of the Universe.

“I had never really given that serious thought and suddenly, it struck me as profound,” Collins said. “All of us inherently, down through history in every culture, have this sense that it is good and it is evil and that we should strive to be good.”

“I know as a geneticist and somebody who studies evolution that there are times where we are called to do things that aren’t really good for our reproductive fitness yet we know that they are good,” he continued. “That seems to say that there is something deeper here than some evolutionary constraint. Did I come to the point be being convinced by scientific proof that God was real and that Jesus was the son of God? No. But I did realize for me that there was an incredible hunger for not just knowing that God was there but having a relationship.”

Collins said he also knew that he couldn’t come to a relationship with God on his own power because of his own “sinfulness.”

“If there was any opportunity to have a relationship with God that had to be offered up by some kind of a bridge, and I finally understood what Jesus was all about and what the cross was all about,” he said. “It meant that I had heard those people say that Christ died for your sins. I had never gotten that and all of a sudden I did.”

According to Collins, he finally gave his life to Christ during a hike on a dewy morning in the Cascade Mountains in the Pacific Northwest over 49 years ago.

“I fell on my knees and I said, ‘I get it. I am yours. I want to be your follower from now until eternity,’” Collins told the audience. “That has never changed since that day.”

The geneticist recalled that there were some doubters who told him after his conversion that his “head is going to explode” because he won’t be able to reconcile Christian faith with science.

“In all those 41 years, I have never encountered a conflict between what I know as someone who takes Scripture with the greatest seriousness and someone who will not accept your scientific data until you show me why it is right,” Collins said. “I think God calls us to do both of those things.

"And I think it is truly tragic that in our world, in particularly this country over the last 150 years, we have set up young people to believe there is a conflict there. I do not see that. God gives us an incredible opportunity as scientists to learn about God’s creation. And that can be a wonderful form of worship. You can meet God in a laboratory.”

Collins is also the author of the 2006 book, The Language of God.

Collins came under scrutiny from Christians and pro-lifers who called for his resignation last December after he expressed support for fetal tissue research during an NIH Advisory Committee to the Director meeting. He reportedly suggested that fetal tissue research could be done “with [an] ethical framework.”

Although many Christians are grateful for BioLogos’ help in reconciling their faiths and scientific theories, BioLogos has also been criticized by conservative Christians and Young Earth Creationists as being an “attempt to persuade evangelical Christians to embrace some form of evolutionary theory.”

Follow Samuel Smith on Twitter: @IamSamSmith

or Facebook: SamuelSmithCP