Pastor Tim Keller on bearing Gospel witness in polarized society (pt. 2)

In an increasingly polarized society, interacting respectfully with those of different beliefs while remaining faithful to Gospel truth can seem like a daunting, if not altogether impossible task.

But according to theologian and pastor Tim Keller, every Christian has an obligation to speak with both conviction and empathy across deep differences, no matter how uncomfortable.

“There’s not a lot of incentive to reach out to people,” the 69-year-old retired pastor of Redeemer Presbyterian Church in New York City, told The Christian Post. “If you get involved with those of different religions and beliefs, it can be costly. There will be misunderstandings, you’ll be vilified, and you may see very little for your effort.”

“The modern self and identity says, ‘There should be an incentive; how does it benefit me?’” Keller continued. “But Christians don’t operate on that basis. They operate on the basis that they have the ultimate benefit, they’re safe for eternity, they’re adopted children of God, they’re citizens of Heaven, they’re never going to lose what they have.”

“The incentive is a desire to be like Jesus; to want Him to be pleased with us, and to want to please Him,” he continued. “At one level, there’s a great incentive, at another level, it could be very costly. Unfortunately, many Christians are operating out of a modern self that doesn’t want to get out there unless it benefits them in some sort of worldly way. We need to step out and ask, ‘How can I walk in the same footsteps as the Lord Jesus who sacrificed in order to reach out to people?’”

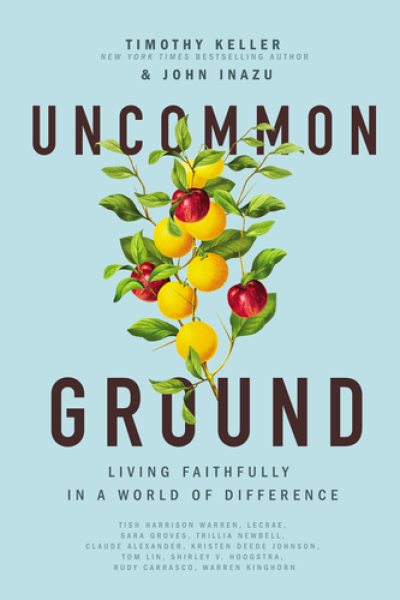

In the newly-released book,Uncommon Ground: Living Faithfully in a World of Difference (Thomas Nelson), Keller, along with Washington University professor John Inazu, discusses how Christians can engage people of all faiths and no faith within a fractured cultural context. The book, Keller said, is the practical outworking of both Inazu’s Confident Pluralism and James Davison Hunter's To Change the World.

In addition to Keller and Inazu, the book features essays from 12 Christian writers from all walks of life, including hip-hop artist Lecrae, singer/songwriter Sara Groves, CCCU President Shirley V. Hoogstra, psychiatrist Dr. Warren Kinghorn, and more.

The various authors “share how they, as Christians, are trying very much to be a distinct culture, but at the same time not combative and look for common ground as much as they can,” Keller said, adding that because Inazu and Hunter’s books are “very academic,” it was important to use stories to “show how biblical cultural engagement is lived out.”

When it comes to engaging culture, Christians commonly fall into one of several categories: “One is being very domineering and trying to take over; one is withdrawing and staying away from public discourse, and one is trying to fit in too much and assimilating and taking up the values of the world,” the pastor said.

The key, he said, is practicing “faithful presence,” meaning “you are faithful to the Gospel and don’t compromise at all and stay distinctly Christian, but you don’t pull away from culture.”

According to Keller and Inazu, there are three specific practices that make civility and peace possible in an increasingly divided society: Patience, humility, and tolerance.

“You exercise humility by recognizing the limits of what you can prove,” Keller explained. “Christians especially should know this — that belief is something God gives us, that reason can only take us so far, and there’s a limit to how much we are saying we can prove.”

“Humility is to say, ‘I know I can’t prove what I’m telling you, because so much of what I’m telling you is based on faith,’” he continued. “We have to be humble as we try to convince each other that there’s a limit to just how convincing I should be. Christians understand that because we know we’re saved by faith and not by reason.”

Patience, then, means “listening, understanding, and asking good questions,” Keller said, adding: “It’s a form of hope. We know that eventually, God will triumph, there will be justice, and every tear will be wiped away. Because we have hope, we can be patient. Patience is a function of Christian hope and humility is a function of Christian faith.”

Tolerance, a “function of Christian love, doesn't mean that you are a relativist about your views,” the New York Times bestselling author said.

“Tolerance doesn’t mean I have to say to the other person, ‘Well you’re not wrong, or you’re partly right,’” he explained. “I can say, ‘You are very wrong, and your views are quite egregious, evil, and offensive,’ and I can still be tolerant. It’s demonstrating compassion because you understand this is a person created by God, not just a pawn or someone I can use or trample on. This is a person of value and worth. My understanding of how God created all of us means I love them even if they’re deadly wrong.”

Keller, who frequently addresses the modern intersection of politics and faith, said that until Christians are able to engage culture with empathy and understanding, they are unlikely to find a way forward in a largely pluralistic society.

“Here’s the trouble: American society has been deeply influenced by Christianity, and that’s something that secular people don’t want to admit,” he said. “So many of our values, like love, human rights, the dignity of the individual, arose from cultures based on the Bible that came out of the Christian West. Yet, secular liberals often don’t want to admit how much of what’s good in our society came from Christianity.”

Conversely, “Conservative evangelicals don’t want to admit how flawed our past is,” Keller said.

“Modern Christians feel like we had a Christian society in the past,” he said. “It was influenced by Christianity, but was it really that Christian? We had slavery, segregation, we mistreated people — as a society we’ve done a lot of things wrong. Modern conservative evangelicals don’t want to admit how flawed our past American society had been.”

“There’s almost nobody with any kind of balance, and that’s one reason we’re yelling at each other,” he contended. “We just don’t understand that in the past, Christianity brought a lot of good things into American society, but American society was very, very flawed and conservatives shouldn’t be nostalgic about the past, because there is a lot of bad in the past. Secular liberals should not be saying, ‘Let’s put the past behind us and completely change because everything in the past was terrible,’ because that is also not true.”

As one of the most influential voices in evangelicalism, Keller knows about engaging hard-to-reach areas with the Gospel. In Uncommon Ground, he recalls how, in the mid-70s, he pastored a church in the racially-segregated town of Hopewell, Virginia. There, he “had to convince church-going people that they did not understand the Gospel and that they were somewhat like the Pharisees.”

In 1989, Keller moved to New York City, where he and his wife, Kathy, planted Redeemer Church with a group of 15 people meeting weekly in an Upper East Side apartment. In the secular north, he was tasked with convincing “people who had rejected the faith that they, too, had never understood the Gospel.”

Though he retired as senior pastor of Redeemer in 2017, Keller remains active in ministry, now serving as the chairman of Redeemer City to City, which has helped start more than 500 churches in dozens of the most influential cities in the world.

According to the pastor, a proper view of our citizenship as Christians change the way we engage with a pluralistic society. “We’re called to love our neighbors, but our citizenship is ultimately in Heaven,” he said, referencing Philippians 3:20.

“However,” he added, “the reality is, we’re also citizens of some earthly county and city.”

Keller noted that when Jesus talks about what it means to “love your neighbor,” He tells the parable of the Good Samaritan — the story of a man who risks his life to “give very practical aid to someone of a different race and religion.”

“That’s who Jesus holds up as a hero, someone who risks his life to give practical help to someone of a different race and religion,” he said. “My citizenship of Heaven should make Christians the very best citizens of their earthly city. We should be the best citizens because we aren’t doing anything on a cross-benefit basis. We’re simply saying, ‘I just need to serve my neighbor.’”

In a hyper-connected world, social media, Keller stressed, is not “conducive” to engaging with those of different views and beliefs with patience, tolerance, and humility.

“The things that go viral on social media are defined by conflict and contentiousness and outrageousness,” he said. “Social media is set up completely to lift up and promote the very things that will hurt society. I’m not saying to stay off of social media; I don’t think you can.”

Before posting on social media, the pastor encouraged users to ask themselves: “Is my tweet, my Facebook or Instagram post, showing patience, humility and tolerance? Is my social media really doing outrageousness and consciousness and insulting people? Or is it reflecting biblical values?”

“The kind of dialogues we’re talking about here simply can’t happen on social media,” he said. “I think you can try to model it on social media, you want to be salt and light on social media, but that’s not the main place to have these kinds of conversations.”

Instead, Keller encouraged Christians and churches to get involved in local politics — an arena he said is “excellent” for face-to-face dialogue with those of different beliefs.

“Churches and Christians need to get involved and say, ‘How can we help our neighborhoods?’ Get involved locally, where you can have relationships and talk to people who are very, very different, yet doing things together,” he advised.

“Once the virus shut down is over, I think there will be lots and lots of opportunities for Christians to join hands with other folks that are trying to do things in neighborhoods that are hit hard,” Keller added. “That’s an important place for these relationships to develop.”