Questions remain centuries after disappearance of England’s first colony on Roanoke

The site of the first English colony in America sits largely overshadowed by the famed beaches on the barrier islands that form North Carolina’s Outer Banks.

In some ways this is fitting, given that the colony on Roanoke Island — explored in 1584 and later settled first in 1585 and then again in 1587 — is called the Lost Colony.

Behind England’s venture was Sir Walter Raleigh, who held letters patent from Queen Elizabeth I for a swath of “remote, heathen and barbarous” land along the Atlantic called Virginia in today’s North Carolina, Virginia and several other states.

Raleigh, along with Sir Francis Drake and other contemporaries, wore multiple hats as courtiers, privateers and explorers during a time when Spain’s status as the great power in the New World was threatened by the growing ambitions of England.

The colony’s location is today preserved by the National Park Service as the Fort Raleigh National Historic Site.

Located about 20 minutes from the beaches in Nags Head, it is a couple miles outside the charming downtown of Manteo. This small coastal town takes its name from an Indian of the same name who befriended English colonists and later became the first Indian baptized into the Christian faith by the Church of England.

Within a year the first colonists had enough and departed with Drake when he arrived in these waters after successfully attacking Spanish ports in present-day Santo Domingo, Dominican Republic; Cartagena, Colombia; and St. Augustine, Florida.

New colonists under the governorship of John White arrived in 1587 and occupied the abandoned structures.

White’s daughter soon gave birth to Virginia Dare, the first English birth in the New World. As with Manteo, she was baptized using the Church of England’s 1559 Book of Common Prayer. The Anglican rites were reintroduced by Elizabeth I after the death of her predecessor and half-sister, the Roman Catholic Queen Mary.

Similar to the first settlement, the latest venture was soon in trouble. So much so that White left for England on a mission to bring more supplies to the colony, which by this time numbered more than 100 men, women and children, including his granddaughter.

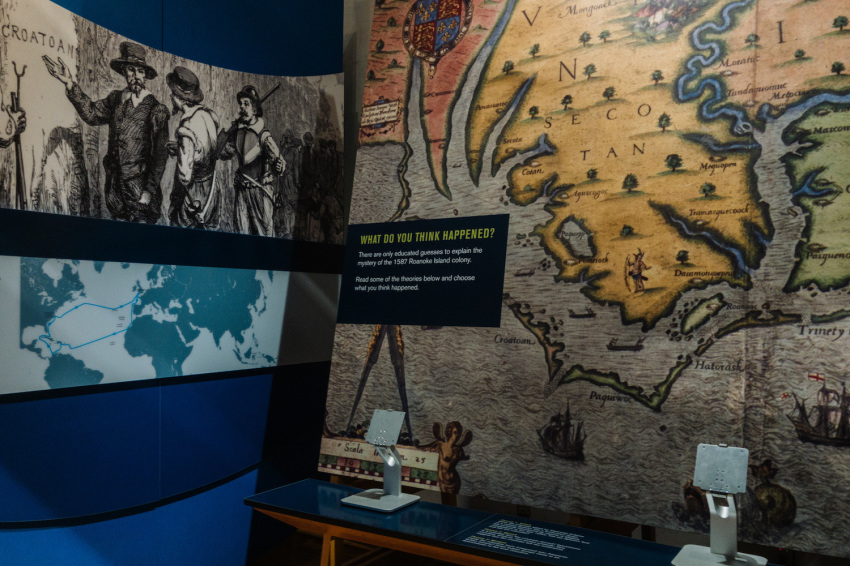

His return was delayed in part by the 1588 Spanish Armada that sought to invade England and, among other things, reverse the English Reformation and restore Roman Catholicism. By 1590, when White finally returned, the colony had vanished. The only clues were two visible inscriptions: “Croatan” in all-capital letters and its apparent abbreviation, “Cro.”

Subsequent attempts by White and even much later by colonists at Jamestown never found anything.

Perhaps most tantalizing is the question of just what happened. As such, it is difficult to visit and not want to know more about Roanoke, at least to the extent that anyone actually knows anything.

I heard several theories during my visit to the Outer Banks. In fact, such speculation seems to be a favorite pastime for locals.

The most common explanation was some version of the English colonists leaving their struggling settlement to live with the friendly Croatan Indians of Manteo’s tribe near what is today Hatteras Island before gradually being absorbed into that culture. Others say they fell victim to disease or were killed during geopolitical conflicts between rival Indian tribes.

Many of the theories are complicated by the lack of archeological evidence, not least any bones to prove colonists were slain by Indians or died of starvation. In fact, outside of a reconstructed earthwork fort from 1950, the finds at Fort Raleigh National Historic Site are somewhat scant.

As a National Park Service ranger told me, centuries of later land use disturbed the grounds.

This opinion was shared by Daniel Hossack, manager of the neighboring Elizabethan Gardens. He said constant erosion caused by centuries of hurricanes and other forces of nature could mean much of the colony’s original location is located off the modern shoreline under the water.

New clues to what happened may come from artifacts recently found about 50 miles from Roanoke Island.

The lack of definitive proof may also explain the longevity of “The Lost Colony,” a play performed outdoors since the 1930s.

Originally written by Pulitzer Prize winner Paul Green, it offers up a dramatic take on the history during nightly performances at an amphitheater about 100 yards from the reconstructed earthwork fort.

If you go

The Holiday Inn Express Nags Head, where I stayed, has million-dollar beachfront views. Visitors more interested in history than beaches should stay at The Roanoke Island Inn or The Tranquil House Inn. Both properties are located in Manteo.

Besides Fort Raleigh National Historic Site, the Roanoke Island Festival Park features an informative museum that also includes Elizabeth II, a 69-foot replica of an Elizabethan-era ship, and costumed historic interpreters.

This year’s production of “The Lost Colony” premieres Friday and concludes Aug. 21.

Follow @dennislennox on Instagram and Twitter.

Dennis Lennox writes about travel, politics and religious affairs. He has been published in the Financial Times, Independent, The Detroit News, Toronto Sun and other publications. Follow @dennislennox on Twitter.