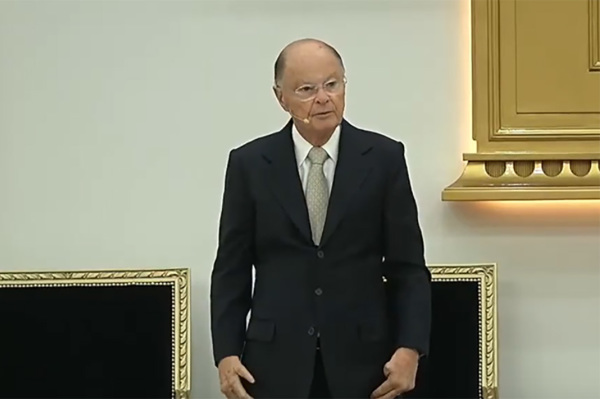

Renowned New Testament Scholar on Bible Translation: What to Read, Why and Myths to Avoid (Part 3)

CP: What would you say are some of the most harmful misconceptions, myths or lies about Bible translation?

Wallace: It's hard to tell exactly... maybe one of them would be that translations that are not done by evangelical Christians or conservative Christians are all bad.

I believe the Spirit of God has so worked over the text of the Bible and the transmission of the text, that even when you get translators that don't believe the Bible is the word of God it's hard for them to mess it up. I think even a translation that's done by people who might be great scholars but may not be Christians can often be very very good translations. A sort of an example of this is the NRSV – although there were several Christians who were on the translation committee, there were also people who were not Christians on it. That's also a very very good translation. I think sometimes we get hostile to certain groups and assume that they are wholly against really what the Bible is really about.

Another myth that I think is very harmful is to think that orthodox scribes have severely corrupted the text. This is the view that Dr. Bart D. Ehrman holds to pretty strongly, and he and I have had three debates with each other over this issue. I think he's overstated the case about how much Orthodox Christian scribes corrupted the text early on.

The opposite kind of a myth, and this is typically held by King James-only folks but others of that ilk, is that heretics have severely corrupted the text, ancient scribes have severely corrupted the text by taking verses out. I think that's a myth that really is harmful for Christians to think that, because they get into the mentality of being suspicious of everything that's out there. The reality is, it's not that heretics took verses out, it's rather that the Orthodox added verses by way of clarification as to what was going on in the text, but it doesn't really change the fundamental theology of the New Testament.

CP: The NRSV also includes the apocryphal writings, correct?

Wallace: There's an NRSV that doesn't have it and the NRSV that does have it. They've got the papal imprimatur on it, which means that the pope has said this is a good, official translation for the Catholic Church and that's the one with the apocrypha in it. Protestant Bibles had the apocrypha in them until the middle of the 19th century, but they would separate out those books by putting them at the end of the Old Testament. If Catholic Bibles integrate them into the Old Testament, they'd call them the Deuterocanonical books.

I'd encourage Christians if they can get a translation with or without the apocrypha, it's always best to get one with the apocrypha. So if you're going to get the NRSV, get one with the apocrypha by all means because that tells you a lot about the intertestamental history, that 400-year gap from Malachi until John the Baptist. It''s important for us to know what happened in that intermediate time... First and Second Maccabees are especially important for telling us some of that information – we know where Pharisees came from, where synagogues, or Sadducees, this kind of thing. You get into the apocryphal literature, you start seeing some of those things emerge and you understand why the New Testament era looks so different from the Old Testament.

CP: There's a suspicion that since the apocryphal works are not inspired Scripture that Christians should ignore them – but you say there's at least an historical value to those texts?

Wallace: Absolutely, they have very important historical value. I think sometimes Christians feel as if "well if it's not Scripture we shouldn't even read it," which is I think a terribly naive attitude, not a good attitude. I think all truth is God's truth, but we need to be involved in reading literature by Christians and by non-Christians wrestling with issues and reflecting all this against a theological worldview.

CP: What are some recent trends you've noticed, good or bad, in regard to Christianity, theology, scholarship, etc.?

Wallace: The single biggest trend that I've seen is a move into the postmodern world, where Christianity is catching up with postmodernism. Some of that is good, some of it is bad. I think what I expected as we moved into postmodernism was a better recognition of the value of the Christian faith as a viable option for how to interpret the data. I expected that because postmodernism inherently says that all truth is relative, there's no absolute truth, that they would say "okay, well you can have your truth, we can have ours" and so there would not be nearly as much hostility toward evangelical Christianity as there'd been in the past. That has not turned out to be the case in scholarship. For the most part, biblical scholars who are not Christians have a greater animosity toward the Christian faith than they did in modernism.

It's ironic because what they're doing is they're saying "all views are created equal except for the orthodox Christian view, that's one that we absolutely must reject." It's terribly ironic. There are revisions that are going on on so many issues about the Christian faith, and things that were considered to be absolutely certain before, are now being questioned. The dates of certain manuscripts, certain beliefs that Jesus suffered the wrath of God on the cross for example, that's being questioned even by evangelical Christians. Virtually everything in the Christian faith has all of a sudden come up for grabs again, as far as some people are concerned.

I think that's distressing because it's basically saying "we don't care about what is the probable view, all views are equally possible therefore we give preference to none, but we do give a non-preference to the orthodox Christian view." It's hypocritical, it's inconsistent and ultimately it's destructive because there's no value as far as the Christian faith is concerned in that worldview.

But the good news about postmodernism – this is something I'm seeing also and that I'm seeing in my students. I can tell within the first two or three weeks of a semester which students are more inclined to be modernist and which ones are inclined to be postmodern. What is really positive about postmodernism is the desire for relationship, the desire for community and the desire for wholeness and authenticity. What modernists would ask is "is Christianity true?" and that's not a postmodern question. The postmodernist asks "is it authentic, or does it work?" In some respects it's a very pragmatic question. … They're saying "I don't want to separate my mind from my heart. I want to make sure that if I embrace the Christian faith it's going to join those two together so I can be a whole person," a whole person in community with other whole persons.

I'm seeing a lot of positive come out of it, but that worldview is affecting all of biblical studies right now. You can't get into any area where it's not being touched.

CP: What 's your advice then, or what would you hope, for the younger generation that will in 20 or 30 years be taking the reigns and guiding biblical scholarship and guiding Christian theology?

Wallace: That's a major question that I have wrestled with and have done so out loud with my students in my classes all the time. Constantly reminding them that they're going to be the leaders of tomorrow, and they need to make sure to know Scripture well, ingrain it into their lives and be walking with the Lord.

One of the things that I really try to insist on is to say "look, neither modernism nor postmodernism is a biblical worldview." But I believe in what's called the communal Imago Dei, or societal Imago Dei. ... The basic belief about the Imago Dei that the orthodox Church has held is that everyone still is created in the image of God. You see that in James where he says don't murder somebody because you're murdering somebody who's been created in God's image, which is telling us that the Image of God is still part of what it means to be human. It has never been lost, it's never been erased, but it has been distorted.

Both on an individual level and on a societal level, the Imago Dei has been distorted. Modernism distorts it, postmodernism distorts it, and yet it hasn't been completely obliterated. Consequently, we can see things in our society that we can approve of, that we can say "I agree wholeheartedly with this, this is a part of how I need to think about the world. Here's something that I disagree with." What's happened as we've shifted into postmodernism is some of the older scholars are saying "well we need to get back to modernism" – no, we don't. What we need to do is recognize is that we need to be above the fray and have a Christian worldview that partakes a little bit from modernism, a little bit from postmodernism, but recognize that all things are subject to Christ and that some of these viewpoints are wrong, some of them are right and we need to have a Christian viewpoint where our minds are truly transformed by the Gospel.

I also remind them that Paul tells Timothy to preach the word in season, out of season, whether it's something that people want to listen to or not. In our postmodern, pragmatic world we have moved the Gospel in the direction of something that is feel-good theology. Rather than telling people what they need to hear, we tell them what they want to hear. That's a real danger the next generation has got to deal with, and it will have vast repercussions if they don't resist that temptation.