San Quentin Inmates Trained to Land High-Paying Tech Jobs After Release Don't Return to Prison

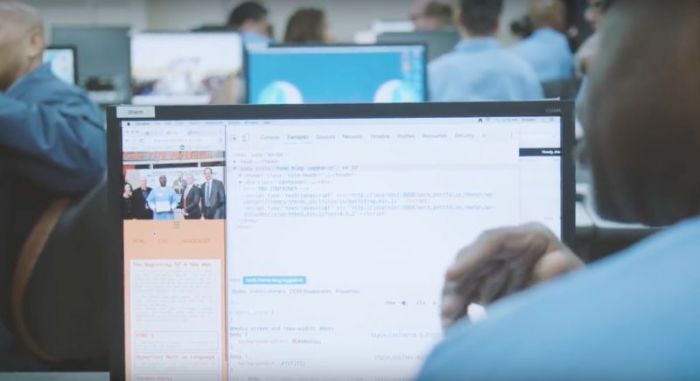

Inmates at San Quentin State Prison in California have successfully redesigned a leading criminal justice reform group's website with little to no internet access with the help a prison reentry entrepreneurship program that successfully trains prisoners for software coding jobs upon their release.

The criminal justice reform group the Coalition for Public Safety — a bipartisan coalition comprised of conservative and liberal organizations — launched its newly redesigned website on Wednesday that was produced with the help of San Quentin inmates participating in The Last Mile Works web development program.

Considering that Bureau of Justice Statistics studies have found that about two-thirds of inmates across the U.S. are rearrested within three years of their release, The Last Mile was created five years ago by Silicon Valley venture capitalists Chris Redlitz and his wife, Beverly Parenti, in hopes of breaking the cycle of mass incarceration by training San Quentin inmates to do computer software coding, a skill that is highly sought after in today's job market.

With a Code.org study finding that there are about 500,000 available computing jobs in the U.S., The Last Mile teamed up with the California Industry Prison Authority and the California Department of Correction and Rehabilitation to create a training program inside San Quentin that teaches inmates the basics of computer coding.

In October 2016, The Last Mile Works web development shop was launched inside of San Quentin. The Last Mile Works operates as a joint venture web development company that employs select incarcerated men who have graduated from the training program to work on web projects for the organization's clients.

Being that the prison has rules against internet access, mock servers were created to allow the inmates to participate on website builds inside the prison.

The Last Mile Works' biggest project to date is the complete redesign of the Coalition for Public Safety's website. It has also done smaller web development projects for clients like Airbnb.

"We are their biggest and most complex project to date. I hope that we can help spawn other sort of big engagements of The Last Mile in this way," Jasmine Heiss, the director of coalitions and outreach for the Coalition for Public Safety, told The Christian Post in an interview.

"As we were looking and thinking about how to redesign our website to best tell our story as an organization and about the reforms that we seek and our mission, The Last Mile was a clear partner in this work," she continued. "Not only do The Last Mile employees who are incarcerated at San Quentin get paid a wage that is comparable with Silicon Valley internship rates, but actually was among the highest paid wages of anyone incarcerated in the United States."

Among the few San Quentin inmates who worked on the redesign of the Coalition's website is Steve Lacerda, who spent over a decade in jail for vehicular manslaughter and was released on parole in late June. It didn't take long for Lacerda, who was the lead engineer on the Coalition's website rebuild, to land a programing job.

"I have always been involved in computers. So even before [going to prison], I was involved in network troubleshooting. It was an easy draw for me once I saw [The Last Mile] application come out. I just applied and got in. From there, I busted my butt and we were able to learn and progress. Ultimately, we got into the joint venture program and from there just continued progressing and trying new things and learning," Lacerda told CP in an interview. "When I got home last month, I finally realized how important all that was because jobs seemed rather plentiful out here for programmers."

The redesign of the Coalition's website was led by a project manager named Aly Tambura, who was also formerly imprisoned at San Quentin.

"What we had done inside is that we kind of envisioned what it would be like and actually started doing some mock up builds. And so, when I came out and met people from the Coalition for Public Safety and actually saw what they wanted to build, it was easy to relay it to the guys inside," Tambura said in a Coalition for Public Safety video.

Eric O'Connor, a San Quentin inmate and engineer with Last Mile Works who also worked on the project, said in the video that working on a project like this has given him "a sense of purpose"

"I actually have something to do and can contribute to other people's lives in a positive way," O'Connor said. "I am very proud of this project."

Heiss told CP that one of the best aspects of a program like the Last Mile Works is that none of the inmates who have participated in the project and have been released have returned to prison. Although no tax dollars have been used to fund The Last Mile or The Last Mile Works programs, Heiss said it would be a good use of tax dollars if state governments decided to fund programs similar to the one offered by The Last Mile at San Quentin in prisons elsewhere throughout the country.

"What if you could scale a program like this beyond the 20 or 30 people who have come home after participating in The Last Mile to even larger numbers? What if you saw that non-existent or very low rate of recidivism expanded with expansion of programs, it would produce massive cost savings," Heiss asserted. "I think that understanding the value of reinvesting some of the cost savings of reducing incarceration into measures that can help people truly correct their lives and not recidivate at the rates that they do across the country is a valuable investment for taxpayers because it ultimately saves all of us money and it contributes to safer, healthier and more mobile communities."

Lacerda said in his interview with CP that one of the biggest problems with prisons is the lack of training programs like The Last Mile Works, which can teach inmates to do other jobs besides welding, machining or physical labor.

"There are some programs where they train you in welding and machining and things like that, but this is the first one that actually aims more toward high-paid forces. I think that is the big difference. I am not going to be a welder. I was a network engineer before I went into prison," he explained. "I think there is need for some of those jobs but I think there is need for other types of jobs that people can fit into. Not everyone fits that one mold that they want to do hard labor when they get out."