Shroud of Turin Bloodstains Likely Fake, Not of Jesus Christ: Forensic Experts

Bloodstains found on the shroud of Turin burial cloth, believed by many to have once wrapped the body of Jesus Christ, are likely fake, according to new research reported in the Journal of Forensic Sciences.

In June 2017, researchers at the Institute of Crystallography found traces of blood on the 14-foot-long relic, with initial analysis of the particles discovering "a scenario of great suffering, whose victim was wrapped up in the funeral cloth."

The nanoparticles uncovered were found to not be typical of the blood of a healthy person.

The Journal of Forensic Sciences report on July 10 revealed that the bloodstain patterns were analyzed in a type of crime scene scenario. In the test, researchers found that the linen seems to have been patched with bloodstains from a standing model, and not from a crucified man or a facedown corpse.

"This is the kind of forensic work done all the time in police investigations," forensic scientist Matteo Borrini from Liverpool John Moores University told BuzzFeed News.

"Even a crucified or hanging person should leave a distinct blood pattern on the cloth, which would be fascinating information to have."

Borrini, a Roman Catholic, said that he carried out the investigation with the aid of chemist Luigi Garlaschelli of the University of Pavia in Italy, initially looking to determine whether the blood patterns match the crucifixion of a person in a T-shaped or Y-shaped manner.

The researchers pumped blood onto a model at the wound points found on the shroud and studied the angle in which gravity pulled the liquid down.

The bloodstains did not match up with any pose, however, with the evidence suggesting that a standing model was used to imprint the patterns for the hands, the chest, and the back.

"This is just not what happens to a person on a cross," Borrini said, noting that the comparison model displayed very different blood angle patterns than the shroud.

He said that his own faith doesn't rely on the legitimacy of the shroud, however.

"The church itself would like to know what things are real, and what are not," he added. "This isn't the Middle Ages anymore."

Jonathyn Priest of Bevel, Gardner and Associates Inc. in Norman, Oklahoma, who is a bloodstain pattern expert, said that while the science and the methodology used in the study were sound, they may not be accounting for when the body was moved such as being carried and prepared for burial.

Priest also told BuzzFeed that the amount of blood from the wrists on the shroud would "more than likely" have needed the heart to have been beating at the time the bloodflow formed, however.

"The fact that flowing bloodstains exist at all on a deceased body that was reportedly cleaned also raises questions," he added.

Besides the blood stains, the imprints and the age of the cloth itself continue to fascinate believers around the world.

In 1988, radiocarbon measurements suggested that the shroud was a forgery made somewhere between 1260–1390 A.D., but later research found that the fibers tested at the time were from a patch added later on the shroud, and not part of the original cloth.

DNA sequencing tests in 2015 found pollen and dust particles from the shroud belonging to plants from South America, the Middle East, Central Africa, Central Asia, China, and other regions.

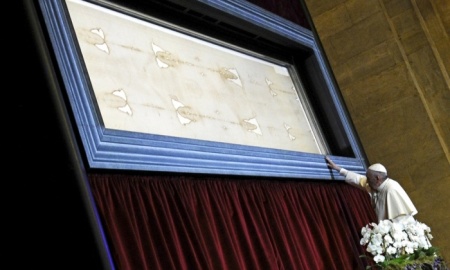

The Catholic Church has never declared the shroud to be a genuine religious relic, but regards it as an icon, attracting millions of people when it is put up for public display at the Cathedral of St. John the Baptist in Turin, where it is kept.