Stephen Hawking's Writings on Creation Are Tangled, Illogical Mess

Theoretical physicist, Stephen Hawking, struggled for over 50 years with a debilitating and slow-moving form of Lou Gehrig's disease. He deserves our respect for this, and so do those who provided the extraordinary amount of support that he needed.

He was an amazing man who had an amazing mind for doing math and an amazing imagination for positing theoretical models of the universe.

In his life and in his death, he has been idolized by many educated people. However, most of us, and even most scientists, have little or no comprehension of many things Stephen Hawking said and wrote.

The book that made him famous, A Brief History of Time, was written for non-scientists, but parts of it are too difficult to read. It has been called "the least-read, best-selling book of all time."

Of course, I'm part of the crowd who understands very little of what Hawking had to say. However, some of his statements are very clear to me, especially when he strayed into the realms of philosophy and theology, where I have some training. I feel comfortable conversing about obvious problems with Hawking's views in these areas. And this is what we'll do now. We'll converse about some of his shortcomings.

Let's consider, first, his complete rejection of philosophy. He and his co-author, Leonard Mlodinow, in their book, The Grand Design, state frankly, "Philosophy is dead." Now this is not a scientific statement. No scientific observation or speculation can confirm or suggest the idea that philosophy — any and all of it — is no longer useful.

Furthermore, their assertion is self-defeating in that the authors are making what is clearly a philosophically-driven statement that denies the value of all philosophically-driven statements, including their own! It's as if they were saying, "We can't speak a word of English" when obviously they can! Their denial makes no sense, and yet the rejection of philosophy is fundamental to everything else written in The Grand Design.

Second, let's think carefully about a theological statement, also included in their book: "Because there is a law such as gravity, the universe can and will create itself from nothing. Spontaneous creation is ... the reason why the universe exists, why we exist."

Now gravity is a force built into the very structure of the universe. So it cannot exist, in some disembodied form, before and without the universe. And this stand-alone gravity, which cannot even be conceived, also has no conceivable mechanism for causing creation.

Then in this same confusing explanation, Hawking and Mlodinow assert that the universe "will create itself from nothing"! But if it already existed, there would be something, not nothing; and there would be no need for the universe to create itself since it already exists! (I would like to see Hawking's grade if he had submitted such a scrambled bit of nonsense to one of my former philosophy professors.)

In summary, Hawking and Mlodinow's explanation of what they call "spontaneous creation" is a tangled, illogical mess.

Third, his call to higher and hopeful goals for the human race are hollow. To find meaning in life, he suggests that everyone start by doing some work in the discipline of theoretical physics. Taking Hawking in his own words, this is the only real hope he gives to people who want to live a meaningful life in a meaningless world.

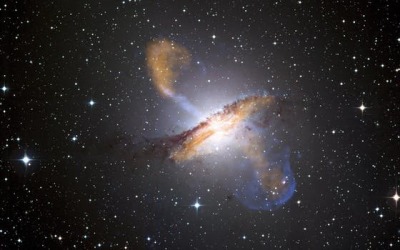

So on one hand, Hawking states that the human race is just "a chemical scum on a moderate-sized planet;" the planet is orbiting "a very average star;" and the star is located in "the outer suburb of one of a hundred billion galaxies." "We are so insignificant," he says.

Then at another time, he gives this description: "We are just an advanced breed of monkeys on a minor planet of a very average star."

But on the other hand, and in bold contrast, he declares, "We can understand the universe. That makes us something very special;" and "Remember to look up at the stars and not down at your feet. Try to make sense of what you see, and then wonder about what makes the universe exist. Be curious."

Finally, he declares, "And however difficult life may seem, there is always something you can do and succeed at."

So after all his contemplation of the universe (that he practiced for decades), the best Stephen Hawking can do is to tell people (who are, to him, fellow scum and fellow monkeys) that, when they have delved into the physics of the cosmos for an undetermined amount of time, they should then be successful at "something" — something that will have nothing directly to do with their cosmic curiosity.

For you see, to Hawkings, thinking about the universe is a detached, wonder-filled activity that's the best thing we can do in life, but it leads to nothing beyond itself!

How hollow, how shallow, how sad. A far cry from what people who are like me can say — we who believe in "God, the Father Almighty, who created the Heavens and Earth."