Study of God in the brain points to a common thread among people of faith, neuroscientist says

In an interview with The Christian Post, neuroscientist Adam Green, senior investigator in a new Georgetown University study that found the strength of an individual’s faith in God is likely linked to the brain, explained how the new data point to a common thread among people of all faiths.

Green and his neuroscientist colleagues conducted the study "Implicit pattern learning predicts individual differences in belief in God in the United States and Afghanistan" published this month in the journal Nature Communications.

They found that an individual’s ability to unconsciously predict complex patterns, through an ability known as implicit pattern learning, had a strong correlation with the strength of their belief in a god who creates patterns of events in the universe.

The study, which involved a predominantly Christian group of 199 participants from Washington, D.C., and a group of 149 Muslim participants in Kabul, Afghanistan, is the first of its kind to explore religious belief through implicit pattern learning.

To measure the implicit pattern learning ability of participants in the study, researchers used a well-established cognitive test in which they had to watch a sequence of dots appear and disappear quickly on a computer screen.

They pressed a button for each of the moving dots but some participants in the study — the ones who registered the strongest implicit learning ability — began to subconsciously learn the patterns hidden in the sequence. They pressed the button for dots before they appeared. Even the best implicit learners in the study did not know that the dots formed patterns, which demonstrated that the learning had happened at an unconscious level.

Green, who is an associate professor in Georgetown University's department of psychology, explained what this could mean for those who believe.

CP: What kinds of reactions have you been getting to the study so far?

Green: It’s been interesting. I think as a researcher, the motivation is to understand things and I think the wider world wants to fit whatever you find into a narrative and it isn’t necessarily the case that the actual data supports a particular narrative one way or another. I think people have a lot of interest in sort of what the study means in terms of whatever their preconceived notions are about belief. And that’s a complicated issue.

It means different things to different people. I think some people have taken it as here’s an indication that somehow religious people are seeing something that nonreligious people aren’t but sort of indicating something deeper. And other people are taking it as well. This is really just people overgeneralizing from the ways their brains interpret visual information. Really I think the point is, the data are just the data. You could be a believer or nonbeliever and these data shouldn’t sway you to be one or another or justify one position or another. It’s about understanding how people come to belief, not whether what they believe is real.

CP: Your study reminds me of the God gene hypothesis (which proposes that human spirituality is influenced by heredity and that a specific gene, called vesicular monoamine transporter 2, predisposes humans towards spiritual or mystic experiences). Do the results from your study point towards a God gene?

Green: Well, I think both genetics and belief would be undersold to think that either could be boiled down to those kind of monolithic terms. I think belief means so many different things to so many different people. It’s such a rich, complex thing and so are genetics. Thirty thousand different genes interacting in so many different ways, no interesting thing that humans do comes from any one gene. That’s not how it works. I do think what we’re finding is that there are hardwired differences between people that influence the way that their brains process visual information and the ways that brains process visual information seems to have some influence on how likely they are to tend toward narratives that emphasize interventionist gods. And so I guess in that sense there is something innate that is biasing people toward or away from belief but it certainly wouldn’t break down to just one gene.

CP: The study involved participants from the U.S. and Afghanistan. Was there any consideration to include participants from places like Sweden where you don’t have a lot of religious people?

Green: If you look deep into the study, we actually did an online sample with Europeans and that was one of the reasons why. We weren’t able to collect all the same data because it was online rather than in person. Some of the tasks don’t work with the online presentation. We were interested in a broad a sample as possible.

CP: How would you explain why some countries are more religious than others?

Green: There is always a temptation to say research found this phenomenon, in this case it’s the relationship of implicit learning to belief, and to try to take that and say how can we explain everything with this one phenomenon. What we are finding, and what science almost always finds is just a small piece of the puzzle.

And I think the genetics here are actually a great analogy because let’s say you find a gene that has some influence on height. Well it turns out, and people have studied this actually, you might find some people in Sweden who tend to be quite tall. You might find slightly more people in Sweden carrying that gene, but it turns out that there’s actually tens of thousands of genes that influence height and so any one gene is just a tiny part of the story. It turns out that proper nutrition influences height and many other things can influence things as complex as belief.

I think to say that it may be plausible based on what we found that a slightly higher percentage of people in more heavily believing places would show greater implicit learning, that is probably a fair interpretation. But there is so much more to the story. This is just one small piece.

CP: America has always been pretty religious but we have been seeing the rise of religious nones (people with no religious affiliation). Why do you think this is happening?

Green: Unless you’re attributing that to some sort of demographic changes where you accept different people, within the same gene pool essentially, you wouldn’t expect to see changes over time at a population level in implicit learning. I’m sure there are many other reasons that people have come up with as to why there are cultural shifts in these things.

CP: What do you see as the next step for the research you are doing now?

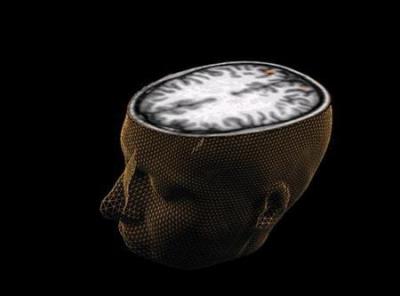

Green: We have a new grant funded [study]. Most of my research is at the neural level looking at the brain. And so we’re going to be doing neural imaging to try to get a clear understanding of how it is that brains represent God, which is a fascinating question, and whether the representation of God in the brain differs by whether people are stronger believers or groups who are self-described nonbelievers, groups that are self-described moderate believers and groups that are self-described strong believers, and looking at whether basically everybody is representing the same thing but believing in it to a different extent or actually representing different things.

CP: What was the sample of believers in Washington, D.C., like? Did you look at different types of Christians by denomination like Pentecostals and Catholics?

Green: Really good question. I have to say my background is not in the cognition or neuroscience of belief. It’s been a fascinating journey and I’ve learnt so much about the richness of it. We didn’t look at those kinds of characteristics as differentiating variables in this study but in our new study we are focusing more on that. It’s one of the things that’s related to how do people represent God? What is the experience? And we’re finding lots of different experiences and then what we have to sort of look at the best way to comparing across them and seeing what are meaningful differences and how can we explain those in terms of the way that the brain is representing God.

To do that, because I don’t have that expertise, we’re working with people who are very experienced religion researchers. Kathy Johnson and Adam Cohen at Arizona State University are a big part of the new study along with some other folks who have a fair bit of experience in that area. I’ll focus more on the neuroscience side, which is more my training. But it’s a great opportunity to get to learn from people who know about such a fascinating topic, which really is the fun of being an academic in the first place. You want to stay in school. You want to keep learning.

CP: What triggered your interest in this study?

Green: What we are interested in is how belief arises in the brain and how God is represented in the brain. Those are things that are of interest to me and to my lab because we are in general very interested in how connections are made in the brain. And so we study those on reasoning based connections, we study those in terms of creativity, we study those in terms of social connections. But there is this idea of connection to something that you can’t see or you can’t interact with directly and so in some ways it’s one of the most elusive connections that there is. And so trying to understand how that happens, how that arises and how that operates in the brain, that’s where our interest is focused. It isn’t a search for God.

CP: Any final thoughts about what this research could do for people of faith?

Green: The thing that I would say is at least from my perspective, is that it’s very encouraging when people who are believers across different faiths who sometimes consider themselves different from each other, and in some cases opposed to each other, can identify something shared that makes them human in the same way. And to me that’s what this research hopefully can say to believers. What I think it isn’t and I hope people take it as this, as I said, a number of people on both sides of these divides, is justification for sort of the veracity of belief or the falsity of belief. That’s not what the data show. That’s not the question we asked and it’s not the answer we got.