The Clarence Thomas Story: An American Masterpiece

This week marks twenty-five years since President George H.W. Bush named Clarence Thomas to the U.S. Supreme Court, inaugurating a tenure marked by unwavering commitment to principled originalism.

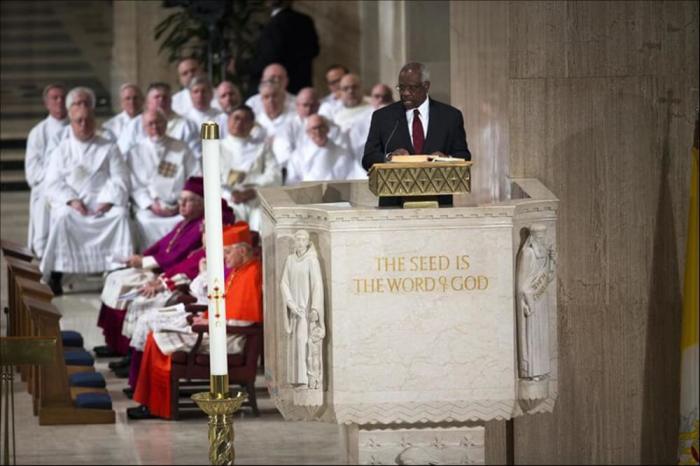

Justice Thomas's life is an only-in-America success story. As movingly recounted in his autobiography, My Grandfather's Son, Clarence Thomas was born into extremely modest circumstances, then raised by his maternal grandparents when his mother became unable to provide for him and his brother. This man of humble origins eventually made his way to Yale Law School, quickly rose through the ranks of public service to become a federal appeals judge, and ultimately ascended to the nation's highest court at age 44.

One of your authors (Blackwell) has been privileged to call Clarence Thomas a friend for more than 30 years, and shared a close advisor who mentored them both, former Brandeis president Morris Abram. Your other author (Klukowski) is a constitutional lawyer and former law clerk to a highly respected federal appeals judge. Looking at Justice Thomas through both of these lenses, he must be called nothing short of a national treasure.

Justice Thomas's judicial opinions reflect who he is as a person: unpretentious, loving liberty, embracing the role that the Constitution assigns to the Supreme Court in our self-governing republic — and emphatically rejecting the temptation to expand the powers of the Court by constitutionalizing his personal preferences. He eschews flowery language and witty turns of phrase in favor of a plain, direct, powerful exposition of what the law is.

His approach to interpreting the Constitution can be summed up in a single word: originalism. Justice Thomas believes that any legal text — whether the Constitution, a statute, or some lesser authority such as a regulation — should be interpreted according to those words' public meaning at the time that the American people's representatives adopted them. It is the ultimate respect that an unelected leader can show to the democratic process.

One of the most remarkable features of Justice Thomas's originalism is how low of a bar he sets for the doctrine of stare decisis where the Constitution is concerned. That general judicial policy — that precedent must be adhered to unless special circumstances require overruling it — can be perilous when the Supreme Court is interpreting the Constitution. If the Court misinterprets a statute or regulation, elected leaders can supersede that decision by amending the law. But it is extremely difficult — deliberately and rightly so — to amend the Constitution.

Consequently, Justice Thomas has called for rejecting even longstanding constitutional doctrines that have set the nation upon a permanent departure from the Constitution's commands. For example, the "dormant Commerce Clause" doctrine says that states cannot pass laws that burden interstate commerce, even when Congress chooses not to enact a contrary interstate commercial statute. Similarly, while the Constitution enables Congress to preempt state laws concerning Congress's powers enumerated in the Constitution, "implied preemption" is a nuanced doctrine that coddles federal power by nullifying state laws that are in various ways at odds with federal law, even when Congress is silent.

Justice Thomas rightly says that he will have none of it. If Congress wants to unburden interstate commerce, it can pass a law to do so. If Congress wants to supersede state law on a matter committed to Congress in Article I of the Constitution, Congress can pass a law expressly preempting those state laws. The current era of muscular federal power showcases that courts need not coddle federal power to protect Washington from the states.

Often Justice Thomas stands alone, such as when he writes that the Constitution's Establishment Clause does not apply to the sovereign states, that federal rights can be asserted against the states if encompassed by the Fourteenth Amendment's Privileges or Immunities Clause, not the Due Process Clause, and that no one has a constitutional right to sell violent video games to children, because in 1791 (when the First Amendment was ratified) children did not have a right to procure objectionable material, and merchants had no right to sell to children without their parents' consent.

Each of these is unquestionably correct according to the original meaning of those constitutional provisions, as seen in their text, structure, and history.

For those who wonder why Justice Thomas would go it alone when necessary, he pointed out to a Federalist Society audience in 2013, "It took Harlan 60 years, but he finally won."

This was a reference to Justice John Harlan's 1896 solo dissent in Plessy v. Ferguson that "separate but equal" is unconstitutional — a position that became the law of the land in 1954 in Brown v. Board of Education.

It other words, Justice Thomas is writing for history: Be right on the law, ignore politics and the passions of the moment, and have faith that one day America — through its president and Senate — may appoint a Supreme Court majority that agrees, and makes it official.

Regardless of whether Justice Thomas's adherence to the original meaning of the Constitution ever becomes ascendant in American law, his legacy is one of which the Framers would be proud.