The resegregation tragedy

Black History Month gives pause to remember the immense cost of bringing down segregation, and how the expenditure is now being squandered by movements seeking resegregation on some levels.

This time it’s not just the white-hooded Klan or police-dog masters, but people and organizations who seem to see it in their interests to keep us divided.

Some call for resegregating college dorms, school boards, and other institutions where once equality of access and participation was rigidly, often violently, forbidden for a large segment of the American population.

Rising generations with no direct experience of a certain historic event or era don’t know the ethos of the long-past age, what it felt like, and thus how to evaluate accurately the threats and fears of that time.

Perhaps people now pushing for desegregation are in generations that have no direct experience of segregated societies.

I saw much of it as a child growing up in the 1940s-50s Birmingham; then in the 1960s as a reporter and editor of The Birmingham News; then, in the early 1970s, as assistant director of the White House Cabinet Committee on Education, formed by President Richard M. Nixon to facilitate the most sweeping school desegregation in American history.

Nixon’s move to end school segregation was as surprising and dramatic on the domestic front as his going to China was on the foreign policy front.

Yes, that Richard Nixon, the old “racist, go-easy-on-the segregated South-in exchange for their votes-southern strategist” Nixon.

At least those were the myths Nixon-haters tried to brew up around him.

But the story is different. I know, because I was there.

When Nixon assumed the presidency on January 20, 1969, he immediately faced a crisis that could destroy public education in seven southern states. They had not complied with court-ordered desegregation handed down in 1954.

The districts were being threatened by federal courts with the possibility of being fined $1 million a day until they were in compliance.

Nixon formed the White House Cabinet Committee on Education to find out why the seven school districts were non-compliant after so many years, what to do about it and to plan for the peaceful opening of newly desegregated schools in September 1971.

The Cabinet Committee found that courts had handed down unfunded mandates. The school systems were barely surviving and now would have to add classrooms, more teachers and administrators, large-scale renovations, and fleets of buses. Nixon sought from Congress $1.5 billion for the school systems. The lawmakers responded with $500 million.

But the human factor still loomed as September 1971 raced toward the communities and states.

How could sudden, massive desegregation be pulled off without community-destroying violence?

How could it be done without giving an opportunity for hate groups to seize control?

How could opposing forces in communities be pulled together to work as units for the survival and safety of those schools?

Nixon formed the high-level Cabinet Committee to answer these questions and provide strategies. Nixon asked Vice President Spiro Agnew to lead the Committee, but Agnew declined. Nixon turned to Dr. George Shultz (who became Ronald Reagan’s Secretary of State) to lead the group.

A strategy emerged that would lead to remarkably peaceful school openings in 1971 and a surprising unity between factions in many of the communities

The Cabinet Committee formed citizen committees in every affected state. Following the model of Nixon’s “New Federalism,” the state citizen committees worked with federal counterparts to propose solutions, give public support to standing with and helping their public schools.

A motto emerged for the 1971 newly integrated schools’ opening: “Keep Your Cool —Support Your School.” Evangelist Billy Graham recorded commercials voicing the motto that played throughout the affected states. Local media outlets within the seven states broadcast the appeals without charge.

We sought the support of pastors and their congregations, and they played a considerable role in helping the school openings occur without violence, as black and white pastors joined the effort.

The local committees worked hard to get participation from opposing groups in their communities. A reporter approached a White House official and told him he was going to run a news story revealing that the head of the state’s Ku Klux Klan was on one of the state committees.

“Yes, you can report that, but you also have to report that we also have on that same citizen committee the state chairman of the NAACP,” replied the White House aide.

Every person on the state committees was a noted community leader. They all had to pay a hefty price: Some for supporting Nixon, who was hated by their constituencies, some for advocating integration, some for being a “lacky” of the federal government. Along with their families, some were sharply criticized, threatened, and cajoled.

But they held their ground.

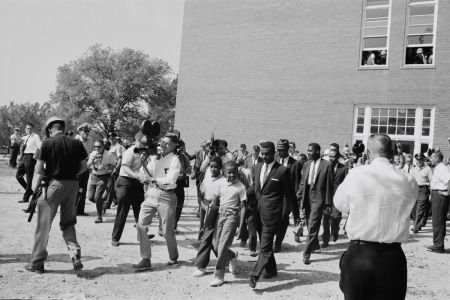

As each state committee was formed, its members were brought to Washington, and to the Oval Office itself. Nixon would greet and thank them personally, then address and inspire the whole group.

Just prior to the 1971 school openings, Nixon flew to New Orleans where he met one more time with the committees.

Weeks before, the first citizen committee to come to Washington was from my native state — Alabama. At one point that day I looked up and saw that I was standing beside Chris McNair. No one had paid a higher price for desegregation. He was the father of eleven-year-old Denise, the youngest child to be killed by a terrorist bomb that exploded during Sunday School at Birmingham’s Sixteenth Street Baptist Church in 1963, along with three of her friends.

Chris and his wife, Maxine, both lived into their nineties. They are gone from us now, as are many from the generations that had direct experience with a segregated society.

Perhaps that is the reason younger generations seem to have little problem in squandering the price the McNairs and so many like them had to pay for desegregation and the hope of an integrated, unified nation.

Thus, Black History month is a good time to remember and thank God for the McNairs and the many others of all races who paid the price to end imposed segregation.

Wallace Henley is a former White House and Congressional aide. He is now a teaching pastor at Grace Church, The Woodlands, Texas. Wallace is author of more than 20 books, including God and Churchill, and his newest, Who Will Rule the Coming 'gods: The Looming Spiritual Crisis of Artificial Intelligence.