To Help India's Poor, Understand Difference Between Pollution and Climate Change

I live in New Delhi, the political capital and the heart of India. This week, the air quality index entered the "red zone."

Air pollution is measured in terms of the average concentration of particulate matter in the air. There are two size categories: PM 2.5 and PM 10 — particles of 2.5 and 10 microns in diameter, respectively. PM 10, at about one-tenth the diameter of a human hair, is far more dangerous than PM 2.5, at about one-fortieth.

This week PM 2.5 reached 178 micrograms per cubic meter, three times the purportedly safe limit of 60, and PM 10 reached 94, nearing the limit of 100.

This makes the air quality unsafe for outdoor activity, including walking. People will face breathing difficulties with prolonged exposure to air. In fact, last year the schools in the city closed for a week following a similar deterioration in air quality.

While Delhi has had this problem for the past two decades, recently people have begun associating it with climate change. But a retrospect into the West's industrial era helps us understand why Delhi is grappling with this air pollution — and it's not climate change.

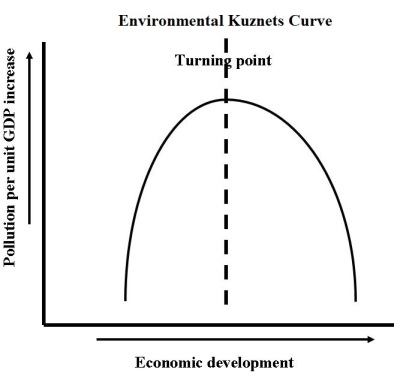

Like many, I was unaware of the environmental Kuznets curve before, while earning my M.Sc. in Environmental Science at the University of East Anglia in England, I studied it. It is an inverted bell-shaped curve that captures how air (and other) pollution and economic development are interrelated.

Almost all countries go through a period of heightened air pollution during their developing phase (as did Europe and the United States). Industrialization rapidly reduces poverty and the hunger and early mortality that usually accompany it. But because early industrialization employs low-tech processes (because they're affordable), it also tends to create more pollution.

As the economy improves, the countries eventually find the technological means and financial resources required to curb pollution in air, land, and water systems. Economic growth continues while pollution declines.

Currently, major cities of India and China find themselves on the upward slope of this curve.

However, India and China do not have to embrace the necessary evil of going through a Kuznets curve for a long period. That is, their Kuznets curves can have shorter times before lower peaks.

Unlike their European counterparts, they and other developing countries can apply clean technologies for power plants and other industrial processes — technologies that took generations to develop in Europe and America but that are available now off the shelf. That translates into a faster, cheaper way to reduce pollution.

The "red zone" situation has become a regular part of people's lives in New Delhi. Every year, in the winter, air pollution hits the worst possible level. The 28 million of us shrug and carry on. We don't like the pollution and look forward to when we'll have applied the technologies to prevent it.

But despite the respiratory discomfort and, sometimes, diseases that come with it, it's better than the hunger, malnutrition, and sometimes starvation that plagued us in generations past, before our amazingly rapid economic development.

How rapidly will our pollution peak and begin to decline? That's largely a matter of how rapidly we grow richer. And, sad to say, those who mistakenly blame our pollution on climate change and prescribe drastic shifts from reliable, inexpensive fossil fuels to intermittent, expensive wind and solar to prevent it offer a cure that's worse than the disease, because it will slow our rise out of poverty and pollution.