Trusting God in Hard Times: A 9/11 Reflection

Today is the sixteenth anniversary of the worst terrorist attack in our nation's history. Since 9/11, there have been at least sixty Islamist-inspired terrorist plots against us. Just this year, Americans have suffered from wildfires, tornadoes, floods, a heat wave, and Hurricane Harvey.

Meanwhile, Hurricane Irma tore through southwest Florida yesterday, leaving more than four million people without power. It is expected to affect Georgia, Alabama, Tennessee, South Carolina, and North Carolina as well.

Christians across the country have prayed for Americans to be spared from the wrath of this unprecedented storm, but millions have been impacted by it. Yet Christians are continuing to pray for God's intervention this morning.

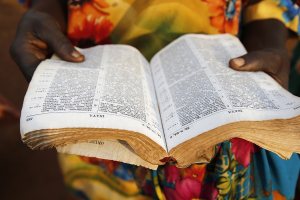

This is typical for us. When God does not do what we ask him to do, we usually decide (1) he will yet answer us, or (2) we did not pray according to his will. In the latter case, we trust that he will give us what we ask or whatever is best. And we remember his word: "My thoughts are not your thoughts, neither are your ways my ways, declares the LORD" (Isaiah 55:8).

But what if unanswered prayer is evidence that there is no God to answer it?

Many of us have wrestled with this problem. We believe that the Bible is true and that we have a personal relationship with the God who inspired it. But when he doesn't answer our prayers as we wish, we can become frustrated or worse. In our dark days, we can question whether he even exists.

British philosopher Antony Flew was once a very famous atheist. He stated that religious faith is "unfalsifiable," meaning that no evidence can persuade its adherents that they are wrong. As a result, he argued, their faith claims are based merely on subjective opinion rather than objective truth.

He would tell us that unanswered prayer should show us that the God to whom we pray is either uncaring, impotent, or nonexistent. But here's what is wrong with his logic: to be susceptible to his criticism, our faith's promises must be unkept but still believed.

Nowhere does the Bible promise us that we will avoid suffering. To the contrary, Jesus warned us, "In this world you will have tribulation" (John 16:33). Nor does the Bible promise that God will always give us what we ask. Paul prayed three times for God to remove his "thorn in the flesh," but the Lord refused (2 Corinthians 12:7–10).

What the Bible does promise is that we serve a risen Lord. If someone could disprove the resurrection, our faith would be falsified and defeated: "If Christ has not been raised, your faith is futile and you are still in your sins. Then those also who have fallen asleep in Christ have perished. If in Christ we have hope in this life only, we are of all people most to be pitied" (1 Corinthians 15:17–19).

We serve a living God whose ways we do not always understand but whose love we can trust.

In addition, faith by definition must persist when evidence seems to contradict it. I don't really have faith in my friend if I turn against him at the first rumor that he has been unfaithful to me.

This is the nature of all relationships—they are based on a commitment that transcends the evidence and becomes self-validating. We examine the evidence, but then we step beyond it into a relationship that cannot be quantified, only experienced.

Try proving that your spouse or best friend loves you. No matter what you say, I can claim that they're deceiving you. You might respond that I would have to experience your relationship to know its reality. That's precisely my point.

All faith is unfalsifiable to the degree that it is faith. This is true of a marriage, a work relationship, or a commitment to God. If we reject any relationship whose merits we cannot substantiate objectively, we will live very lonely lives.

(By the way, Flew later turned from his own atheism, writing There Is a God: How the World's Most Notorious Atheist Changed His Mind.)

What does this discussion mean for those of us praying for God's protection in hard times? It means that we can continue trusting what we don't understand to the God we do. Such faith can claim significant precedent.

In Acts 12, King Herod murdered James, one of Jesus' leading apostles. He then arrested Peter, intending to execute him as well. Did the church reject the God who allowed such attacks on his people? To the contrary: when Peter was imprisoned, "earnest prayer for him was made to God by the church" (v. 5).

Why do you need to follow their example today?

Originally posted at denisonforum.org