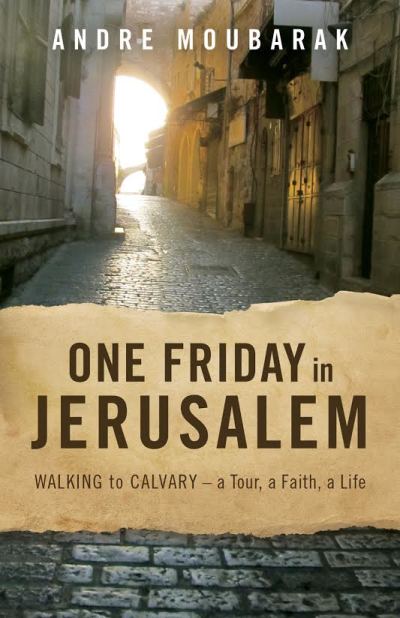

Understanding Jesus Through the Eyes of an Arab Christian, Jerusalem Native (Interview)

An indigenous Arab Christian from Jerusalem is connecting Western Christians with believers in the Middle East in a new book to help them understand the moments leading up to Jesus' death and the Gospel through an ancient near Eastern lens.

In One Friday in Jerusalem: Walking to Calvary – A Tour, a Faith, a Life, author Andre Moubarak, 42, who hails from the Old City of Jerusalem and can trace his roots back to the ancient city to before the time of Christ, takes readers on a journey through The Stations of the Cross, the successive moments beginning with Pilate's condemnation of Jesus all the way up to His crucifixion and burial.

Moubarak grew up on the Via Dolorosa, which means "Way of Sorrows," the street in Jerusalem widely believed to be the path that Jesus walked carrying His cross on the way to be crucified.

"[Life] was never boring," the author recounted of his childhood, "because you meet people from all over the world."

As a young child tourists would routinely ask him all kinds of questions, including questions about Scripture, thinking he might know the answers since he was a native of the city. If he didn't know something a young Andre would go ask his dad or study and read the Bible so he could answer their questions the next time he was asked. He did not recognize the value of those streets but would come to appreciate their spiritual and historical significance later in life.

Although Christians have religious freedom in Israel, Arab believers, especially in Jerusalem, do indeed suffer at the hands of both Jews and Muslims. Moubarak spends 14 chapters of One Friday in Jerusalem — one for each station of the cross — poignantly explaining what life was like in the ancient city, recalling memories from his own life and how it relates to Jesus' teachings in the Gospels. The author told CP that though he wrote the book over the course of five emotionally taxing years that were full of many hardships, it was an ultimately healing enterprise for him.

In Chapter 2, "Jesus Takes Up the Cross," Moubarak recalls a time in 1987, one year after the first Intifada began, when he was outside playing in the streets, unaware that a riot was underway in a nearby market. An Israeli soldier asked him what he was doing and when he replied, "Nothing!" the soldier aimed his rifle at him and pulled the trigger twice, dry-firing his weapon, terrifying a 12-year-old Moubarak. He had to walk past this particular soldier in order to get home and was hoping to avoid another incident but he was not so lucky. The solider smacked him hard across his face. He ran home crying afraid for his life.

"Lest it sound like I'm singling out Israeli soldiers," Moubarak writes, "I assure you that, for a Palestinian Christian, oppression comes from every side."

On another occasion he had gone with friends to play near the Damascus Gate in East Jerusalem, a predominantly Muslim section of the city. A local boy approached him and asked him: "Are you Christian or Muslim?"

"Christian," Moubarak replied, with a big smile on his face.

"Wham! Out of nowhere he hit me in the face," the author continues, "I reeled back in pain and confusion but otherwise did not react. I was too stunned to do anything except, instinctively, turn the other cheek, not realizing I was doing exactly what Jesus said I should do when mistreated (Matthew 5:39)."

Evangelicals from non-liturgical traditions will not be as familiar with The Stations of the Cross. The object of the stations is to help the faithful make a spiritual pilgrimage through contemplation of the Passion of Christ, meditating on what Jesus experienced at each step along the way.

Today, Moubarak leads tours of the Holy Land with Marie, his American-born wife, with their company Twins Tours & Travel, taking Christian tour groups, 90 percent of which are evangelical and 10 percent Roman Catholic, around Israel.

"Seeing all the Catholics who would come [to Jerusalem] to walk the Via Dolorosa, in front of my home and they were very sad all the time. And they focus only on the suffering of Christ," he recounted.

By contrast, when evangelicals travel to Israel they do not care so much about walking the Via Dolorosa — Moubarak describes the streets that comprise it as often dark and depressive — and they almost exclusively focus on the resurrection, he said. Evangelicals usually do not pay very much attention on this part of the tour but as he explains the meaning of each station their ears eventually start to perk up, he said.

"So we need the balance of the suffering because we appreciate what we have when we suffer and we appreciate the power of resurrection."

When many American Christians think about Arabs they tend to think that they are Muslim, and they simply do not know about Christians living in Israel, he continued.

"We are a minority among a minority among a minority, so all the believers in the Old City, the indigenous believers, are not more than 300 people," Moubarak said. He doesn't blame Americans for not knowing about them.

"But I want to tell [American Christians] that Palestinian Christians are Spirit-filled Christians from the early Church who are good people and are walking under persecution and a lot of pressure from both the Muslims and the Jews."

Such consistent spiritual and physical pressure makes their witness for Christ particularly strong. God is using them mightily because they are not recognized, Moubarak says, but their stories and voices are starting to get out.

The Jerusalem native also aims to build another bridge, connecting the chasm between the Eastern and Western mindsets. Jesus, an Aramaic-speaking man in the Middle East, would have operated with an Eastern way of thinking.

"The Eastern way of thinking is based on families," he explained, the family unit is of the utmost importance.

The Middle east mindset also centers on community, not on the individual. Individualistic thinking is especially futile when their community is a very small minority, he noted.

"This is how Jesus functioned in the first century," Moubarak went on to say. "It's about relationships and making disciples, about how effective you are in the Kingdom," and not about growth numbers and metrics that Westerners tend to value. One Friday in Jerusalem, then, functions somewhat as an invation for Christians to get reacquainted with their Middle Eastern roots.

The author stressed that his main hope is that readers in the West will be inclined to connect with Eastern churches, with the Body of Christ in Israel and in the Middle East, reiterating that the gap between the East and the West needs to be lessened.

He advises churches in the West: "Don't be scared of the news [pertaining to Middle East affairs]. The news is so much of an exaggeration. They won't tell you exactly what is happening in Jerusalem. Come here and meet believers in the churches in the city."