What Christians Should Know About Intersectionality

A concept appearing more and more in American political discourse and on college campuses is "intersectionality," a theory that is becoming a political movement that noted Christian thinkers consider contrary to the Gospel.

Broadly defined — though its precise meaning is disputed — "intersectionality" refers to the interconnected nature of social categories like race, gender, class and how these identity markers create overlapping and interdependent systems of disadvantage or discrimination.

For example, when applied to a distinctly American context, in light of history and the discrimination shown to women as well as the systematic racial prejudice shown to black people, intersectionality holds that a black woman is at a greater disadvantage than both a black man and a white woman and is even more disadvantaged than a white man. An additional layer of disadvantage would appear if the black woman was also a lesbian, this theory holds.

Prominent theologians and thinkers have written in recent weeks about how this way of viewing the world is at odds with the Christian faith even as it may highlight societal injustices.

Here are three things you should know about intersectionality.

1. The theory is based on a long list of identity categories that often compete with each other regarding who is the most oppressed.

Novak Journalism Fellow Elizabeth Corey writes in the August edition of the journal First Things that the term "intersectionality" originated in a 1989 article by black feminist Kimberlé Crenshaw about nondiscrimination law. Crenshaw fleshed out this idea by explaining a 1977 case where five black women who had been fired from General Motors sued the company, arguing that they had been wrongfully terminated because of compounded racial and gender discrimination. The women were unwilling to sue on the basis of just one factor alone, insisting that both physical traits together were used against them in their firing.

Over the years, "intersectionality" has been expanded to include "studies that integrate the disadvantages caused by sexual orientation, class, age, body size, gender identification, ability, and more," Corey noted.

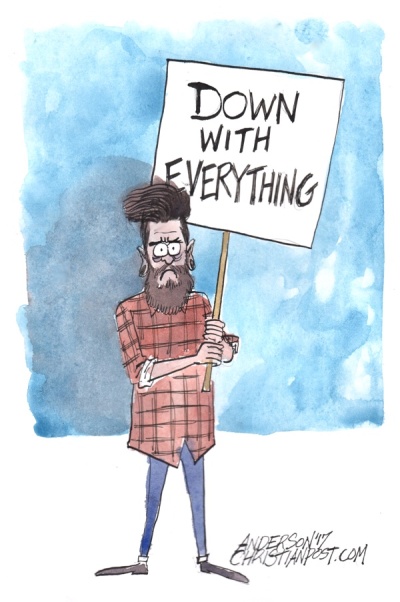

With a growing list like that, some have noted that this theory thus creates a kind of "oppression Olympics" and that even those who hold to the theory are actually less empathetic to people they purport to care about in light of the competition about who has been more victimized collectively.

In March of this year, the European Journal of Social Psychology published three studies showing "evidence that concerns over the societal recognition of collective victimhood can be associated with intergroup animosity."

"In some societal contexts, in which formerly victimized groups that have no common history of intergroup conflict live in the same society and do not compete for other reasons, competition over collective victimhood recognition can be the main, or even the sole, source of intergroup tension."

2. The theory may highlight real phenomena found in the Bible, but is ultimately incompatible with Christianity.

To the extent intersectionality appears in Scripture, it could be argued that it is seen in the Gospels in the story of the Samaritan woman at the well who was known for her promiscuous sexual history in John 4. Both women and Samaritans had considerably lower social standing in the male-dominated, Jewish culture of the day. Sexual sin in particular was shamed significantly, making Jesus' interactions with her that much more radical.

But intersectionality theory does not point to redemption in Jesus Christ, in whom there is neither Jew nor Greek, slave nor free, male or female, (Galatians 3:28), as theologian Denny Burk pointed out on his blog earlier this month.

Intersectional theorists nevertheless aim to inspire people spiritually toward some kind of redemptive purpose and urge disadvantaged people to engage in solidarity and political activism together. But just what they are after is unclear in that deep differences often exist among certain subgroups. In this system of thought, the more victimized the individual the more moral authority he or she supposedly has and should be given, but the arbiter is not known.

Burk added that this theory "fails to distinguish between social categories that are morally neutral and those that are morally implicated."

"Whereas the Bible celebrates racial diversity and the complementary differences between male and female, it does not celebrate sexual orientation diversity. The Bible says that all sexual activity outside the covenant of marriage is sinful, but intersectional activists would view such a judgment as oppression when applied to gay or bisexual people."

Because intersectionality includes sexual expression and gender identity in its list of categories of oppression, it insists that homosexual practice must be promoted and celebrated, and it redefines gender such that the transgender identities are accepted as normal.

"This too is a radical departure from Christian teaching about how integral biological sex is to human identity as male and female," Burk said.

3. Although an indisputably politically liberal movement, intersectionality is illiberal and in some ways is already pitted against itself. Conservatives and any other liberal dissenters need not apply.

Practically speaking, for all its attention to marginalized and disadvantaged persons, some groups cannot fit at all into the intersectional paradigm no matter their race, gender, body size, or class: conservatives and straight white men.

During a seminar at Notre Dame, Corey asked Patricia Hill Collins, a sociology professor at The University of Maryland-College Park, who is considered one of the architects of intersectional feminism, whether and how proponents of the theory might find common ground with conservatives who disagree with them.

"No," she replied with vehemence.

"You cannot bring these two worlds together. You must be oppositional. You must fight. For me, it's a line in the sand," she said.

Rod Dreher, author of the New York Times bestselling book The Benedict Option, observed on his blog at The American Conservative on July 18 that one cannot even argue with people who believe in this theory "because they see reason itself as a tool of the oppressor." Intersectionality is, he said, "a militant religion."

"You can only resist and defeat them. They work as a revolutionary vanguard because they understand, at least intuitively, that the old-school liberals they're up against do not have the courage or self-confidence sufficient to resist them in the name of liberal values," Dreher said.

"Mainstream liberals are the useful idiots for these radicals, and when they have served their purpose, will become either their converts or their victims. Because that's how this militant religion works."

Corey further noted that despite calls for solidarity among oppressed groups, intersectionality may produce even more separation and conflict than cooperation.

"One major goal of intersectional theorists is to distinguish increasingly fine-grained markers of oppression, separating people into ever smaller classes with distinct interests," she said.

She added: "While women may constitute a large group, the group of disabled black women is far smaller. This group's interests are not necessarily the same as those of Latinx lesbian women. Indeed, these groups may even be at odds in significant ways. In this respect, then, intersectionality divides rather than unites.

"There are already signs of such division among the movement's more radical members, who view elite white feminist women with a contempt that nearly matches their contempt for white men."