What Is It Like Serving as a Missionary in a War-Torn Country Dubbed the 'Worst Place in the World to Be a Woman?'

PCUSA Missionary Co-Worker: Despite Difficulties There Is 'Immense Joy' Among Empowered Survivors

Boyd: I think we live out our mission through relationships. I think it will be difficult to live out Christ's mission without relationships so it is a relationship with those around us or those we have come to serve, which can also be at a distance. As you mentioned, we serve in different countries, so I will be in a different kind of relationship but it will be in coordination and in mutual mission with our partners in those other countries.

I don't know how much you know about PCUSA, but the way that the PCUSA is in mission is through partner churches. It does not have its own mission station or mission office, etc. (There are) autonomous denominations with which the PCUSA has a partnership and then through that partnership, mission personnel is sent to serve with those partners. So just as a little clarification because sometimes when you mention mission — I don't know what your readers group is — but there is still the idea often that the mission church is the decider and the one running things and managing, etc. That is not the paradigm with which the PCUSA works.

[Editor's note: Boyd clarified via email after the interview that she was "grappling with the term 'mission' in this time and age, because the root of the word seems in contradiction with the paradigm of mutuality with which I serve as a Presbyterian mission co-worker. This is too complex to be formulated into a definition that would correctly represent the understanding from which I engage in my role as mission co-worker in the field."]

CP: Tell me a little bit about the specific work that you do.

Boyd: Since a year, my role has changed. I had another role for the last 13 years. My role now is Facilitator for Women's and Children's Interest. Now that could still be very general. It's a new position that has been created by the Presbyterian World Mission as part of the reorganization and restrategizing in this new era of missions. Part of strategizing is bringing more into focus the interests of women and children since they very often are sidelined, are being marginalized in decision-making processes or in economic processes or by culture. It is a role that I'm still working on trying to give shape. Our partners have of course their ministries, their programs. I am trying to first get to know what are the programs and how women's and children's interests are involved. Now many people when they're hearing women's and children's interests, their thoughts go automatically towards, 'OK, then I will be working in women's ministries.' And what's often understood with that is say the women's departments in the partner churches, that is a segregated way of going about women's and children's ministries issues.

We're looking at systemic structural problems that keep women and children from developing their potential. Those systemic problems need to be addressed by the whole community and are not just ministries, projects, whatever that women's department may be setting up. In my role, I'm looking at all three main strategies, what's called Critical Global Initiatives by the Presbyterian Church. One of the three CGI's is "Sharing the Good News of God's Love in Jesus Christ." For this CGI the PCUSA is particularly focused on training leaders for community transformation. In my role, I would engage where the well-being of women's and children's concerns are involved.

For example, in Congo, a major issue of the last decade — before it was also an issue, but it has become worse — that is child witch accusations. Children accused of being involved in sorcery, in witchcraft. This has also to do with a very different world view and even within Christian circles there is a different world view than we have say in America or in Europe. But what has evolved is that many children are being abandoned … some of the revivalist churches have very violent exorcist practices and so there is a lot of trauma going on for children. Our Congolese partners are trying to look at this issue. The Evangelism Department, the Life of the Church Ministry is looking at how to address this issue as a Christian missionary church, a church that has evolved from the early missions. But as the partners say, they as mainstream churches have not been equipped by the early missions to deal with witchcraft as a reality in their cultural context.

At this moment, these last few years, the church is trying to look at how to equip its pastors to help families and communities deal with their fear about their children being in some way affected by witchcraft. So that is a whole community-based issue. You cannot address that by engaging just with the Women's Department. The Evangelism Department is a huge part of that, and so is the Development Department. For that theme, for Congo, that falls under "Sharing the Good News of God's Love in Jesus Christ" by training leaders for community transformation.

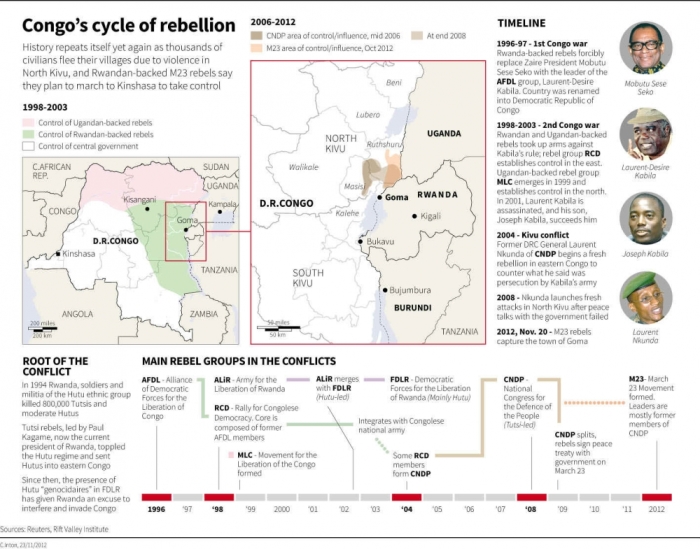

Another CGI is "Addressing Root Causes of Poverty in a Globalizing World," particularly where it impacts women and children. You can think of various things. You can think of human trafficking and also sex tourism, which is an issue in Madagascar, or the ways a country's natural resources actually make life worse for women and children and Congo is one particular example. I just returned from the east of Congo to visit to Goma where the natural resources have been exploited by various arms groups to fuel their conflict but at the same time they also have been applying sexual violence as a tactic of war and intimation of communities. The sexual violence has continued, even though what is called "war" in the official sense is over — in terms of a beginning and the end. There are still roaming militias that are raping women and young girls. Raping and also very brutal killings. So a lot of this kind of violence is related to the exploitation of natural resources and then you get to a globalizing world because the minerals don't stay in the country. They go all across the world and may be processed into electronics that you and I are using, so that makes our world connected. The fact that women and children in certain situations are victims of that is something that our church wants to look at. The third Critical Global Initiative is "Engaging in reconciliation amidst cultures of violence including our own," which includes a campaign to End Violence Against Women and Children.

So keeping in mind each of these three Critical Global Initiatives as mission foci, I listen to what our partner churches in Africa are lifting up as issues in their communities and society that affect the well-being of women and children, and how they seek to address those concerns. I share that with my colleagues in World Mission and invite churches in the U.S. to come alongside our partners' efforts, because the partnership paradigm for Presbyterian global missions these days has become multi-dimensional. Over the years it has evolved from a centralized model with a mission society operating on behalf of the church as a whole, to a decentralized model where we as staff at the Presbyterian center and in the mission field inspire, equip and connect Presbyterians in the pews for us all to work in synergy with each other and with global partners to further God's mission. In the PCUSA we speak now of Communities of Mission Practice, where we network in areas of common mission interests. Many feel drawn to do so through hands-on projects, others will want to help build capacity of church leaders, and some become advocates to change unjust systems. It's through these collective efforts that we hope to be the most effective. We all get transformed, converted in some way, in the process.

Some of the other cultural issues are widowhood practices, cultural practices that affect widows here in Congo, child miners, or the exploitation of women and children in mines, rape in conflict zones as I mentioned, child migration in Rwanda has been lifted up by the church, sex tourism has been lifted up in Madagascar as well as human trafficking in Madagascar, child, early and forced marriages have been lifted up in South Sudan.

I just returned from Niger as a first visit in the context of this new role and that's where I heard particularly the important role of the women in supporting the evangelism work and the role of the wife of the evangelist because she has access to women in communities where the women still need to stay in the home. So there is some kind of a transformative role for the spouses of evangelists or women evangelists in Nigerian communities but I'm still kind of processing some of my experiences there. But that's kind of how I approach this new role within the new strategy of the PCUSA. And then giving it an approach with things so that by looking at systemic problems maybe there are ways that can be done through advocacy to change some of these systemic problems. It's so much and the questions are pretty seems simple but the responses, you can't give a very simple response.

CP: Is there a priority between evangelism and addressing social needs? Do you ever find that there's a conflict where you have to address the people's basic needs before you try to tell them about Jesus?

Boyd: It's not I who determines that evangelism needs to be done. On the one hand, the Presbyterian World Mission has worked with the global partners to identify these three critical global initiatives. So those have been set by the Presbyterian World Mission. I'm trying to look at each of those where women and children are concerned. And then again, I'm trying to discern what the partners are lifting up but there may well be conflictual situations where there are cultural aspects affecting women and children that need to be addressed. They are lifted up, sometimes by the women's department, sometimes by the development department, or by chaplaincy program. But where maybe the deciders in the church are still very much a male hierarchy, there are times that for the women it's an uphill battle. There are situations like that. There are other situations in which there is great support for initiatives. There are sometimes still also theological questions where churches still may not ordain women where maybe women would have more access to other women in order to share about the good news. For example in Niger where women are not ordained, but there are only women who can really have access to women in the community, some of the Muslim communities where women are still very much tied to the home.

CP: Throughout your experience in the past 25 years in different countries where you have worked, what are some of the personal dangers that you have encountered politically or spiritually? What are some of the hard and difficult things about missions?

Boyd: I'm not sure whether I would directly point them out as hard or difficult things. If you formulate them like, what are some of the risks, then I would say that it has been different in the different countries at different times. Like I said, we've had two evacuations out of Congo in the '90s. One we could see evolving but you really needed to be in touch with what was happening, because there were risks, talk about coups possibly, rumors, etc. Those have been tense times.

The first time it was a prolonged pressure, not a spike of high pressure and danger or whatever, but it was a prolonged pressure that at some point has a depressing influence. The second time was over night, literally and some hard decisions needed to be made. I think what was particularly hard was the feeling of we have come to serve a community here, the church here. Yet all indicators were is that this was not going to end well. We needed to [make a] very quick decision. The children were young and we don't [make] those decisions alone. We talked with the church in the U.S., we talked with the partners here but that was… The first one was easier to take because it was actually the partner church that said you know — where we lived in the capital city of Kinshasa, [it] was anticipated [that it] was going to be taken in one or two months' time and you never know how that would end in violence — and so the partner church indicated that they preferred us to leave because they said we want you to continue to serve with us, and in order for you to continue serving with us it's best that you leave now because we've seen too many mission workers get traumatized and not return so we prefer that you leave now and then you come back when the city is taken. So we did.

It's just the second time things developed differently and we kept in mind what the church had said in that first situation and discussed with the church in the U.S. and together we decided that it was best that we would leave for the children. That was a very hard decision because you are abandoning, you feel that you're abandoning the partner because also over the years with various violence and rioting in conflict it has become clear that sometimes when missionaries stay they become a liability for the partner. The partner church becomes more concerned about the missionaries and then cannot take care of its own community and its own families. So it's also in the interest of the partner churches, at times depending, of course you discern everything, but that second time that was also a consideration that it was better to leave. That has been difficult. The political instability here in this country has been difficult.

Now we went to Cameroon and there was not the political instability there. It's relatively stable even though probably people would desire for a better situation. But there is political stability. At one time we had the food riots in 2008. Some of the earlier experiences helped deal with that. But in Cameroon what was difficult for us was they were waves of violent crime where groups would invade houses and they would also use violence. So those waves were...that's a whole other kind of insecurity than political instability but it's still difficult. Another is road safety. When we were in Kinshasa in the mid-nineties, we could not get out of the city, but in Cameroon it felt like a great freedom to be able to get out of the city, now get in the car get out whenever. But the road safety in the sense of accidents, that became a concern. There have been many deadly accidents in that time, actually my husband and son have been involved in a school accident, a deadly school accident. So there might be political stability but then there are other things.

But then again, you know everywhere where you are, life has it dangers and its insecurities, everything is relative. But if you're asking specifically, then I would say those probably have been the things that stood out in our experiences.

PHOTO...CONGO RAPES

CP: Are there any particular aspects of your work that, despite the risks and dangers, really give you joy, that kind of confirm for you that missions is what you've always wanted to do or what you should be doing?

Boyd: Yes, that is getting out to the grassroots. I have felt very privileged to be in a very privileged position of being able to get to some of the most remote places and getting to know the situation in which people live, the challenges that they have, the opportunity to listen to their challenges and put them in a larger context so that I could interpret that back home so that… Sometimes those are cutting-edge things and there are risks involved but it is also a very unique privilege situation in which I can be the eyes and ears of the many people who cannot get out there. And for me also the responsibility to lift up those situations back home in the U.S. so that together we can discern how best to approach those situations to make life better for those at the margins. That is what gives me joy, that's where I feel is my calling.

Again I was in a situation just this last week in the east of Congo, I think where very few people have had… I feel like I need to be careful in how I phrase this because it's not, it's definitely not meant in a sense of...I don't want to dramatize or sensationalize or whatever, but there are situations that are utterly deplorable, sad, I don't even know what to say. I will just share this with you. I don't know if it would be suitable to go in your report but just so that you know what I'm talking about. I visited with Debbie Braaksma, the Africa coordinator, she was in Congo and it was decided that we would also go to East of Congo where the women's department of the Federation of Protestant Churches is helping survivors of rape. So they have a shelter where they can go to, they have trained counselors that listen to the women. We're talking here about very brutal rape (frequently gang rape) where the bodies of the women are internally torn up so sometimes they need surgery.

I have been there in February, I heard some of the experiences at the hospital and this time we were going to go into the interior. There had been stories surfacing that, even though it's known that these rapes continue, in some parts in East Congo there currently is an heightened violence. We discussed with the partners and the partners said no, that's farther away than where we will be going. So we decided that we would go. But we did hear from women who had come in just the day before walking a long distance who had experienced a month ago, in August and September, they'd been raped but also their children were butchered, they were hacked by machetes, etcetera. These are stories that women told us themselves.

I still need to process this but you know, I need to think how can I in a responsible way convey this reality to our churches in the U.S.? What does it mean for the role of our churches and for me as a mission worker? I'm talking with the department of this Federation of Protestant Churches. ... So on the one hand I will look with the church and other partners [about] what can be done advocacy-wise. But I'm in a very particular situation or role in which I do get to hear these stories and these are very brutal stories. I have been in other situations where there have been injustices that may not have been as brutal, but at the economic scale major injustices. These are stories that I feel called to convey to people in the U.S. so that they can start to better understand how their lives are related to the lives of these people that I meet and how we can work together to change systems to make life...so that these kinds of injustice and cruelties [will] one day come to an end.