Why Jemar Tisby is wrong about the economics of systemic racism

“Whatever of mechanical talent or intellect, capable of illustrating a nation, there is in the three millions of slaves is lost for ever for want of education....”

—Cassius Clay, 1848

The American debate over race is heating up again, this time in Christian circles. Jemar Tisby complained this week about the controversy swirling around his appearance at Grove City College. Tisby authored The Color of Compromise, a book that takes on the history of the white church’s unwillingness to join the fight for Black civil rights, and he has now joined Ibram X. Kendi’s Anti-Racism Center. I, for one, believe that Grove City students are smart enough to hear a wide range of views and evaluate them. Here, though, I’d rather address a particular claim of Tisby’s to see what it can teach us about economics and the natural law. Tisby defends himself against the accusation that he believes all white people are racist and insists instead that “all white people benefit” from racist systems. I argue that, taken as a group, white people don’t genuinely benefit from Black oppression at all. The exclusion of any minority group from freedom of movement, education, economic participation, or the equal protection of the law never benefits the majority group. It only lessens them.

Let’s start with the institution of slavery. That slavery is immoral is clear, but there has been a long-standing debate in the field of economics over whether slavery is profitable. What do we mean by ‘profitable’? Of course, slaveholders profited from the unpaid and unfree labor of those they enslaved, although they made no higher profit margins than northern employers of free labor did. But to notice the profit of particular businessmen is different from asking whether the institution was profitable. When we ask that question, we are asking whether it expanded the economy, that is, whether it increased wealth generally. Economists are often derided for being cold-hearted numbers people, but credit where it’s due: they insist on counting everyone’s preferences in the aggregate, not just white people’s! Factor in the physical and psychological losses to enslaved people – lost freedom of movement, lost wages, lost family members, lost leisure, lost learning (and therefore human capital and future earning power), and so many other losses, the costs to the overall economy are immense. And we haven’t even touched on the dysfunctional economic effects of slavery: infrastructure that was never built, poor white workers’ wages also bid down, labor wasted on slave patrols and overseers, and high rates of violent crime in the south. When compared to the alternative of an economy based on the liberty of all individuals and free trade, a slave economy can never compete. Instead of growing the real amount and quality of goods and services through innovation and free exchange, a slave economy is mostly just a wealth transfer, stealing from a large number of people and moving that wealth to a small minority of owners through violent extraction.

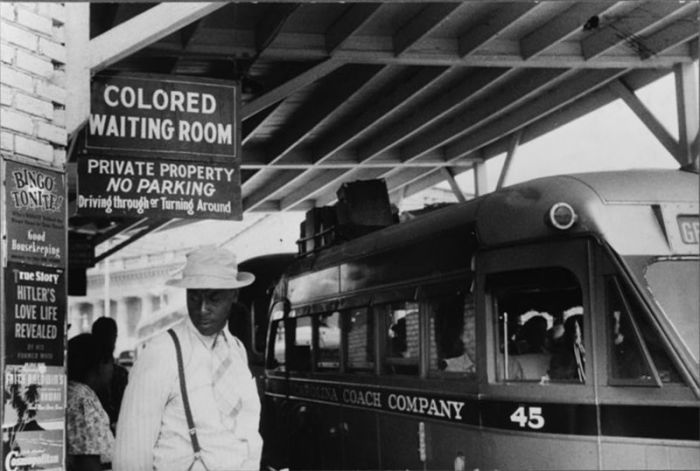

A similar argument can be made with regard to Jim Crow and the Black codes in both the north and the south. Every time we make it harder for people - particularly people who are already marginalized and struggling - to learn, trade, move, and build, we impoverish ourselves. There is no economic advantage to excluding one group, because it only leads to missing out on their contributions. The choice to disrupt and ghettoize black communities through FHA red-lining policies, urban highway construction, and so-called ‘urban renewal’ (slum clearance, otherwise known as ‘negro removal’) partly caused the concentrated inner-city poverty we see today. The costs are astronomical: high unemployment, high crime, high rates of drug addiction and corresponding disability, poor educational outcomes, poor health outcomes, and high incarceration rates. Would someone please explain to me how all of these high costs benefit white people? A few of them might benefit some middle-class bureaucrats (black and white) who hand out benefits or serve as prison guards. But all of us – including those I just mentioned – would be living in a far more thriving economy if the federal government had left well enough alone so that the mixed income neighborhoods that were developing prior to their interventions had been allowed to grow organically. Instead, the Feds decided they needed to helpfully social engineer the way that white and black people interact, and now we’re dealing with social and economic consequences that will take decades to heal.

The same could be said today when it comes to petty occupational license requirements, overregulation on small business, out of control and unaccountable prosecutors, union pushback against school choice, NIMBY zoning laws, and marijuana bans. While we no longer have laws that discriminate against Black people outright, we raise barriers to economic participation that affect all marginalized groups. It’s about time we jettison the idea that oppressing and excluding anybody benefits the rest of us. The beauty of the free society is that the freer the people, the more they can, and will, benefit one another.

Rachel Ferguson is the Director of the Free Enterprise Center at Concordia University Chicago, Assistant Dean of the College of Business, and Professor of Business Ethics. She is an affiliate scholar of the Acton Institute and co-author of Black Liberation Through the Marketplace: Hope, Heartbreak, and the Promise of America..