Voters in Search of Hitler, Not Churchill

Today we have Hillary Clinton announcing that "everyday Americans" need a "champion," and that she is it, the woman who would be king. The "everyday Germans" in 1930 were looking for a champion that would deliver them from the devastation, humiliation, and deprivation afflicting them after the First World War and Treaty of Versailles. They thought they found that champion in the man who would be called Der Fuhrer.

Ben Carson promises voters that his presidency will "heal ... inspire ... revive." Sounds more like the job description of a savior than a president. Carly Fiorina will bring us "new possibilities" when what we really need is the old principles. Bernie Sanders promises the "coming" of a "political revolution" — creepy words from a man whose philosophical forebears gave the world the 1917 Bolshevik Revolution.

Marco Rubio will establish "a new American century." He must be dizzy from too much time on Mount Hubris. There he has probably already bumped into Donald Trump who pledges that he will "make America great again."

We could speak of all the other would-be presidents and overwrought promises currently and throughout the political past of America and most other nations.

All these triumphalisms are more the rhetoric of the Nuremberg rallies than the exhortations that came out of No. 10 Downing Street when Churchill was in residence. While Hitler was screeching about German greatness and its right of global dominance, Churchill was saying this: "I have nothing to offer but blood, tears, toil, and sweat." That will necessitate the determination to "fight on the beaches ... the landing grounds ... in the fields and in the streets ... in the hills; we shall never surrender."

Not good fodder for a soundbite campaign. Just the hard facts that require the kind of will and endurance that arise from character.

Hitler, on the other hand, was giving the people what they wanted. They were hearing his tirades but not listening; otherwise they would have seen him for the tyrant he was rather than flocking to him like some great hero arising from the mists of Teutonic legend. Yet those same people, wafted aloft by the promises of a new nationalism, created Hitler, and foisted him upon the world.

Many outside Germany, even in Churchill's Britain, were buying into the Hitler rhetoric. They succumbed to the equivalency that suggested that Hitlerism was as virtuous, if not more so, than the "Christian civilization" for which Winston Churchill crusaded. From equivalency in principle comes ambiguity in policy, confusion about national purpose and identity, and ultimately disaster.

Yet for some 1930s aristocrats and even commoners in Britain and America, Hitlerism was the wave of the future. His Germanic nationalism would bring the world out of its languor, and inspire new progress, they hoped. On St. George's Day 1933 — the year Hitler became chancellor in Germany — Churchill lamented that "the worst difficulties we suffer ... come from the unwarrantable self-abasement into which we have been cast by a powerful section of our own intellectuals."

Thus it was a perilous time for Germany and the world.

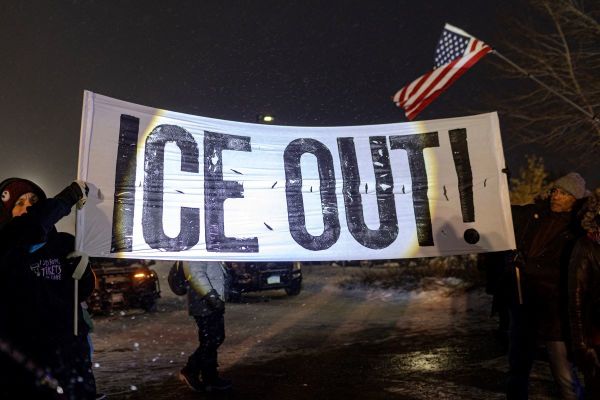

This is also a dangerous moment for American politics. New nationalisms always bring new tyrannies. Consider the shocking restrictions on speech and even thought in America. Contemplate the vastness of the rising regulatory nature of government. Reflect upon the abolition of borders. Think about the frightening expansion of judicial tyranny.

Read between the lines of candidates' slogans. Consider favorably those who summon us to character, and see through those who appeal only to our pride by deluding us with promises of "greatness."

Otherwise we may get Hitler rather than Churchill.