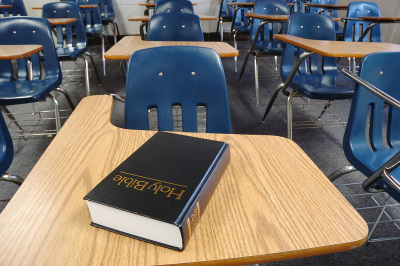

Christians belong in public schools too

With millions of American children returning to school this month, parents of faith must understand their child’s religious liberty is not checked at the public school door but has a rightful place in public education, thanks to the U.S. Constitution.

The U.S. Supreme Court affirmed this over 50 years ago and ruled in Tinker v. Des Moines that students do not “shed their constitutional rights to freedom of speech or expression at the schoolhouse gate.”

The Constitution demands that religion receive equal status and treatment in the learning environment. Simply put, religion is not a constitutional orphan in the public educational system.

To prohibit religious expression in the public education system would be to strangle the free minds of students and teach them that the fundamental rights enshrined in our nation’s charter are mere platitudes that can be ignored at the whim of some antireligious zealot masquerading as an educator.

Students, parents, and teachers should understand that the First Amendment absolutely applies in public schools. Students and teachers have the right to silently pray, engage in religious discussion with their fellow students and teachers, access student activity fees for religious groups, distribute flyers and literature on an equal basis with nonreligious literature, read their Bibles during non-instructional time, and engage in any other religious activity that does not create substantial disruption of the learning environment.

If the school allows students to engage in their own personal expression during non-instructional time, it is prohibited from excluding personal religious expression during the same time frame.

Good news for religious liberty

In a country besieged by immoral behavior and attempts to remove God and prayer from the public school and the public square, Liberty Counsel has worked to ensure religion is protected in the school system and that religious organizations like Child Evangelism Fellowship (CEF) and its after-school Bible clubs for elementary students are not discriminated against in the education system.

With the most recent win against the Hawaii State Department of Education, we have represented CEF’s Good News Clubs in states nationwide for over two decades, never losing a case and ensuring its after-school Christian clubs have equal access.

In 2001, the Supreme Court decided Good News Club v. Milford Central School, holding that a public school must treat Child Evangelism Fellowship equally with all similarly situated nonreligious organizations desiring to host character-building educational programs for students.

The Court held, and rightly so, that there is no constitutionally significant difference between the invocation of teamwork, loyalty, and patriotism by nonreligious groups and the invocation of Christianity by Good News Clubs. The significance of this fundamental principle of religious speech should not be underestimated.

Not a ‘constitutional orphan’

If the school opens a forum for programs of interest to students, the First Amendment prohibits the government from treating a religious organization like CEF’s Good News Club as a constitutional orphan.

The Constitution demands that CEF and its Good News Club receive equal treatment in public schools, and if it allows a nonreligious group to access district facilities, it must extend the same access to CEF.

Many school districts have attempted to find an exception to that concrete constitutional principle, and they have all failed. The reason for that is simple: The First Amendment is obstinate in its demand for nondiscriminatory treatment of religion, and there are no exceptions to that First Amendment stipulation.

The U.S. Supreme Court has said that “the vigilant protection of constitutional freedoms is nowhere more vital in than in the community of America’s schools,” where the classroom is intended to serve as the archetypal marketplace of ideas.

Public schools can’t be ‘enclaves of totalitarianism’

Education is intended to teach students how to think, not what to think. And far too often in our current system, school administrators get it backward, thinking that students must all think a certain way, adopt a certain set of ideals, and forget what their religious and moral convictions prescribe.

Contrary to what some would argue, students are not closed-circuit recipients of the ideas, thoughts, beliefs, and practices that only a select few school administrators deem suitable for their education. Indeed, the Supreme Court has said that schools are prohibited from operating as “enclaves of totalitarianism” in which the state possesses absolute authority over the students and their methods of thinking.

It cannot be denied that the nation’s future depends upon a well-informed and educated electorate, and schools must serve as a microcosm of the larger Republic in which students and teachers are free to express their opinions, convictions, and religious beliefs without fear of reprisal.

Eighty years ago, the Supreme Court made clear that “[i]f there is any fixed star in our constitutional constellation, it is that no official, high or petty, can prescribe what shall be orthodox in politics, nationalism, religion, or other matters of opinion or force citizens by word or act their faith therein.”

The Court finished that profound national commitment by noting that its guiding light was without “exception.” And so it should be.

In a nation born on the will to be free, it should come as no surprise that our education system is not designed to infringe on religious freedom, and that includes the freedom of an evangelistic after-school Bible club for elementary school students.

Daniel Schmid is a constitutional attorney and the associate vice president of Legal Affairs with Liberty Counsel, an international nonprofit, litigation, education, and policy organization dedicated to advancing religious freedom, the sanctity of life, and the family. Since 2012, Daniel has been on the front lines of litigating many critical First Amendment issues and has taught constitutional law at Liberty University School of Law.