Divided by a common Bible

In this highly-charged political atmosphere, Evangelicals are engaged in a sometimes not-so-civil civil war. America is not the New Jerusalem, nor Israel restored. We are not a Christian caliphate, nor a theocracy, nor even a Christian nation by virtue of an established church. Yet, we are a nation whose founding was rooted in Christian faith, and in recognition of a Creator from whom all human rights derive, and thus a nation humbling ourselves “under God.”

Christian patriots love this country because it has been a God-honoring nation, with a freedom of religious expression that is the envy of believers around the world. The foreboding loss of this freedom, together with deep concerns about a dramatic decline in the nation’s moral character, has prompted voting for one party over another. Though certainly complicated by issues of personal character at the highest level, politics today is not morally neutral.

If what anybody means by “Christian nationalism” is a belief that our richly-blessed nation is “Thy Kingdom come” on earth, or that America is God’s chosen vessel for saving the world, then we’re talking about a straw man. While there were indeed Founders who spoke of “Christian nationalism,” most Evangelicals today who identify as politically conservative would affirm none of the above. It is, instead, politically-liberal Evangelicals who paint such a skewed caricature, insisting there is too much entanglement between Kingdom and country (while happily politicizing their own passion for Kingdom-inspired social justice).

Naturally, each side of the Evangelical divide appeals to Scripture. How can anyone miss Amos’ call to care for the poor and defend the oppressed? Or Jesus’ teaching about the counter-culture Kingdom of God in which “the least of these” must be the focus of Kingdom concern? On the other side, there’s “Thou shalt not kill,” which must surely include the sacred life of “the very least of these” who are aborted in their thousands. How can one be concerned about black bodies at risk without even passing mention of those most vulnerable: black bodies being sucked from the womb? Given the irreversible difference between life and death, there is no moral equivalence between abortion and other social injustices. So, which proof-texts should prevail?

And then there’s the matter of mission versus methods. Alleviate poverty? Absolutely. But the question is HOW? Is there anything innately unchristian about a rising capitalistic tide floating all income boats? One thing is certain: Jesus was not Robin Hood. And, yes, it’s hard to believe Jesus wouldn’t shed tears over children in cages, but can we be certain he would advocate open borders? Or embrace—as many Evangelicals do—Black Lives Matter, the 1619 Project, the “cancel culture,” or politically-correct inclusivism? Nor must one presume too much from Jesus’ silence on any issue of current controversy. You say Jesus didn’t single out abortion or gay marriage as crucial Kingdom issues? Nor did he call for the emancipation of slaves or the liberation of women. All too easily, WWJD is in the eye of the beholder.

“Kingdom witness” through social action versus political efforts to preserve a godly national culture is as much a false choice as “fixating on the world to come” versus fighting injustice in the here and now. That both sides can point to Scripture for support suggests there’s an element of truth to each. For Evangelicals to find harmony, neither partial truth must be allowed to dominate. Only the whole of God’s radical truth in all its uncompromising fullness.

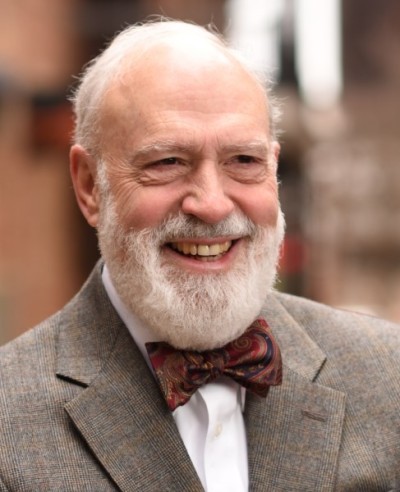

F. LaGard Smith is a retired law school professor (Pepperdine, Liberty, and Faulkner law schools), and is the author of some 35 books, touching on law, faith, and social issues. He is the compiler and narrator of The Daily Bible (the NIV and NLT arranged in chronological order), and posts weekly devotionals on Facebook, drawing spiritual applications from current events.