It’s been 100 years since the Tulsa Race Massacre: Have we learned anything yet?

The low, moaning sound of a cello catches my ear as the doors to First Baptist Church of Tulsa’s Race Massacre Prayer Room open. On the walls hang historical memorabilia —black-and-white photographs, newspaper editorials, quotations from survivors, Red Cross buttons faded from time and wear. All date back to May and June one hundred years ago when the worst civil rights disaster since the Civil War took place.

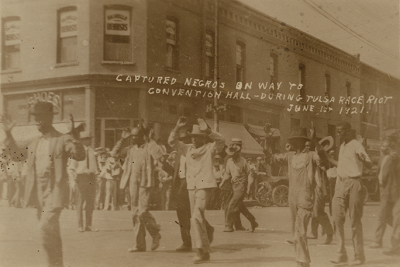

The 1921 Tulsa Race Massacre.

‘Massacre’ is the word we use today to describe the events that unfolded when white men took up arms and marched down Black Wall Street, a prominent stretch of affluent black-owned businesses and establishments in downtown Tulsa. They rushed forward in mobs under the guise of avenging an unproven young white woman’s claim of assault. The rumblings of racial animosity, vehemence, even economic jealousy, however, had long been the driving force behind what took place on that warm night of May 31st. A single spark was all it took. One proverbial match. And the entire Greenwood District — thirty-five square blocks in all — was set ablaze.

I stand and stare at the photographs that hang on these cream-colored walls. They depict a destruction rarely mentioned in high school textbooks. One photo shows smoke billowing up from atop three-story buildings. Another shows Mt. Zion Baptist Church (or what was left of it) as despairing faces sift through its smoldering rubble. Twelve churches were burned that day. So were five hotels, four drug stores, eight doctors’ offices, thirty-one restaurants, and one public library.

Even worse, no one really knows the number of black people who died. Best guess? Probably three hundred, according to information provided by the Tulsa Historical Society and Museum. What we do know is several hundred men, women, and children limped or were carried into makeshift Red Cross tents. Gunshot wounds, burns, even miscarriages brought them in. The cello plays again its lonely dirge.

Have we learned anything yet?

Out of my periphery, I see an editorial hanging on the opposite wall from me. The graininess of its oversized reproduction makes its words appear distorted, inflammatory yet still legible. The title reads, “It Must Not Be Again.” Here is the start of a worthy prayer, I think. But quickly I realize this editorial is not fodder for spiritual petitioning. These words printed in the Tulsa Tribune (a mere four days after that blood-spattered May night) spew hate, blame, shameful unholy ignorance. Would mothers have read these words to their children? Would they have prayed? Would we now?

Have we learned anything yet?

Nearby, sermon quotations about the massacre taken from white ministers of various denominations strike a similar blow as this editorial. One plaque hanging offers no quote at all. It simply reads, “archives are mysteriously silent.” Mysteriously silent? I hear the cello play again.

Next comes excerpts from a 1921 Red Cross report pinned to the wall. In spite of archival silence, this church — my church — did serve by opening its doors to house black refugees. Those with no homes, no livelihood, nowhere else to go took up residence for a time behind the walls of this 120-year-old building, a structure that stood not more than a few blocks from the laid-bare Greenwood District. But was it enough? Is it enough? A piano plays underneath the cello’s melancholy refrain. A weak song of hope?

Have we learned anything yet?

I move to the final station of this Prayer Room. Sample prayers hang by the exit sign, offering parting words for the speechless and dumbstruck. I pray these words, for I too am wordless. But before I leave, I turn once again to that blasphemous editorial. God, it must not be again. These words I speak out loud in utter defiance. I confess them. I declare them. I proclaim them because perhaps if Christians here in Tulsa, all over this nation, and all over the world would hear the truths displayed on these walls, a massacre of this proportion or even a singular proportion — one precious life lost — would never happen again.

Perhaps a holy indignation might rise up. Not one that seeks violence but volition. Not one that evokes fear but ushers in fearless humility, the Christlike meekness and courage we need to learn and change and grow.

Have we learned anything since the 1921 Tulsa Race Massacre? I’m not sure. But as I close these doors behind me, I earnestly pray we don’t let another hundred years go by before we do.

The Tulsa Race Massacre Prayer Room is open for visitation now through June 1st during regular business hours Monday-Friday and from 8:30-1:00 p.m. on Sundays. Donations can also be made to the Greenwood Rising History Center, a center honoring the history of the Tulsa Race Massacre, through their website or through First Baptist Church of Tulsa’s website. The church will match total contributions up to $5,000 for this important work in our community.

Ginger McPherson is a pastor’s wife, Bible teacher, and devotional writer for Journey Magazine and The Joyful Life Magazine. She holds a Ph.D. in English from Baylor University and currently resides in Oklahoma where her husband serves as one of the pastors at First Baptist Church of Tulsa. Connect with her on Instagram or at glmcpherson.com.