Social infertility and the denial of reality

One of the features of the sexual revolution, especially in these latter days, is the steady stream of new words invented in the wake of increasingly incoherent ideas. For example, the word “cisgender,” coined by sociologists in the 90s, refers to “those who continue to identify with the sex they were assigned at birth.” It’s a definition loaded with ideas, such as sex being assigned at birth, but it basically means boys who identify as boys and girls who identify as girls. Only a culture committed to normalizing dysphoria and de-normalizing biology needs a word like that.

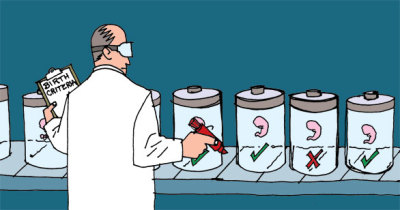

More recently, but in the same spirit of social engineering through nomenclature, some activists have suggested a new take on infertility, not based on biology or reproductive health but on lifestyle choices. The term is “social infertility,” and it refers to the state of those who intentionally choose sterile sexual arrangements, such as same-sex relationships, but still want children.

Proponents Lisa Campo-Engelstein and Weei Lo argue for the term this way: “Expanding the current definition of infertility to include social infertility will elevate it to a treatable medical condition, justifying the use of ART [assisted reproductive technologies] for such individuals.” Further, they continue, “States with infertility insurance mandates should provide the same infertility coverage to socially infertile individuals as physiologically infertile heterosexual couples.” [emphasis added]

Assumed here is that everyone has a right to babies. So, if you want one but are in a relationship unable to procreate, technology and the government should adjust accordingly, and force employers, hospitals, doctors, and insurance companies to help you have a baby. To be clear, this is not yet law, but this same “universal parentage” line of thinking was used to legalize commercial surrogacy in the state of Washington a few years ago, and the Department of Health and Human Services has indicated this kind of language may find its way into new mandates.

The irony is that the very concept of “social infertility” undermines the “love is love” slogan that has so effectively advanced the social innovations of the sexual revolution, such as same-sex marriage. Clearly, same-sex love — even when committed, sincere and monogamous — isn’t the same as heterosexual love in terms of what intercourse means and its procreative potential. Therefore, new words need to be invented, and others redefined.

Redefining “infertility” in this way demands that a slew of other important words, such as “medical condition,” be redefined as well. If an otherwise healthy man and woman fail to conceive a child together, it’s reasonable to suspect a deeper medical condition. Two men (or two women), however, will never be able to conceive a child together. And, when they can’t, nothing has gone wrong. No one suspects their inability to conceive is due to disability or sickness. All that’s left is to create a new category of discrimination.

Advocates of so-called “social infertility” suggest it is unjust when two men or two women cannot conceive and that, therefore, the government should step in. This assumes, of course, that conceiving a child is a “right” even when biologically impossible, an idea only plausible in a culture in which the value of children is tied wholly to whether or not they are wanted. If terminating preborn life is justified when a child is not wanted, then all it takes to justify conceiving a life is that it is wanted. This leaves other words like “rights,” “discrimination,” “equality” (not to mention “men” and “women”) up for grabs.

Imagine demanding insurance coverage for leg augmentations or transplantations in order to sprint as fast as Usain Bolt. Is not being able to sprint as fast as Bolt a medical condition? Do I have a right to claim discrimination because I want to sprint like Bolt but can’t? Do I have a right to force hospitals, employers, and insurers to cover the cost so that I can have what I want? Using the logic of “social infertility,” the answer to each of these nonsensical questions would have to be yes.

What comes under the guise of social fertility is just as nonsensical but far worse, for two reasons. First, for most of us, not being as fast as Usain Bolt is not directly related to any life choices we have made. That kind of dream is not even a remote possibility for me. By contrast, the overwhelming majority of those who claim “social infertility” has intentionally chosen naturally infertile relationships. Had they chosen a different relationship, conceiving a child would be possible.

Second, most artificial reproductive technologies today are justified solely by adult desires, while children’s rights are forgotten in our ethical reasoning. So, increasingly, we behave and pass laws as if having children is a “right” we have or, even worse, as if children are products to be obtained.

This whole conversation reveals how thoroughly the inherent connection between sex and procreation has been severed in our society. Abortion enables us to have sex without babies by killing the natural result of human sexuality. Claims to so-called “universal parentage” leverage artificial reproductive technologies to have babies without sex.

To be clear, the invention of “social infertility” as a concept is just the latest fruit of this thinking, the inevitable result of denying moral and biological realities. The church will not be in a place to respond unless we get our own thinking and our own decisions in line with reality.

John Stonestreet serves as president of the Colson Center for Christian Worldview. He’s a sought-after author and speaker on areas of faith and culture, theology, worldview, education and apologetics.

Kasey Leander is a Fellow with the Oxford Centre for Christian Apologetics (OCCA). Prior to his time at OCCA, Kasey earned an undergraduate degree in history and PPE (Politics, Philosophy, and Economics) from Taylor University. While at Taylor, Kasey served in various ministry roles on campus and was active in student government. He has also worked briefly in politics, serving as an intern in the US Senate in Washington, DC.