What we can learn from those quarantined in the past

The title “Typhoid Mary” entered the cultural lexicon in 1908 via the Journal of the American Medical Association. Today the name refers to anyone who knowingly or accidentally spreads a disease to others. But “Typhoid Mary” originally referred to a specific person: Mary Mallon.

Mallon was born in Ireland and in the early 1880s migrated to America, where she embarked on a career as a cook for well-to-do families in New York City. She was good at her job and had no trouble finding work. Yet, strangely, medical authorities noticed something peculiar about her: wherever she worked, members of the household came down with typhoid fever — and some died. Mallon herself was completely asymptomatic and resisted the idea that the illnesses and deaths were connected to her.

Eventually, Mallon was investigated and quarantined in isolation for three years at a New York clinic where she was forced to undergo medical testing. Upon her release, she agreed to stop working as a cook and to take extreme cautions to prevent infecting others. But the same pattern developed when she found employment as a laundress; she was arrested and quarantined again in 1915. She died under quarantine some twenty-three years later.

Forced quarantines are not unusual in medical history. But the coronavirus pandemic of 2020 introduced a relatively new term: “self-quarantine,” also known as social distancing. Around the world, hundreds of millions of people voluntarily confined themselves to their homes for dual reasons: to avoid contracting the coronavirus known as COVID-19, or to avoid spreading the virus to others until it was certain that they were not a carrier.

Self-quarantining has had many unanticipated consequences, including feelings of isolation, abandonment, fear, loneliness, and despondency. Human beings truly were designed to experience life together.

In the Bible, we learn that David experienced a period of self-quarantine in his own life. Seemingly without warning, he was forced to flee from Jerusalem — including the temple and the palace court — because of a rebellion led by his own son Absalom. Right under the nose of his father, the king, Absalom convinced a strong coalition of citizens that the son should take the place of the father in the palace of Jerusalem.

Keep in mind that we’re talking about David, the people’s choice — king by popular demand as well as divine appointment. This was the hero who had slain the giant, outlasted the tyrant, and multiplied the kingdom! The very idea of a coup was in itself unthinkable, a poison-tipped sword to his heart. But this rumor that the source of a coup was his own precious son — well, that was enough to send a father to an early death by broken heart. He deeply loved Absalom. And Absalom was set on destroying everything that David had fought and survived and perspired to build.

There was no recourse but flight from the palace and even from the city. What a tragic moment for a leader of historic significance! The man who need not fear stepping into the very presence of God had to flee for fear of his own son, his own flesh and blood.

How can we identify with an extraordinary life like that of David? You’ve probably never lived a life on the run because of an angry king, but an angry boss may have kept you on the run. You may never have been the object of a political coup, but you may have felt the pinch of younger coworkers pushing you off the corporate ladder. You may never have fled your home to protect yourself from your own child, but you may have felt the heartbreak of children who failed to honor their father and mother as they grew older — or, recently, you have likely been forced to remain in your home for weeks and months when you much preferred to go out.

In moments like those, you’ve found yourself in deserts that had no sand, deserts of personal desolation, spiritual despondency, and emotional depression. When that moment of ordeal arrives, we’re almost never prepared in body, mind, or spirit.

For me personally, one of the most difficult elements of the coronavirus crisis gripping our nation is that I can’t be in church with my congregation. I know you’re smiling, nodding, and saying, “Of course, Pastor Jeremiah! You’re the preacher — that’s where preachers like to be!”

But it runs a bit deeper than that. It’s not about preaching, but the experience of genuine, godly worship in the context of the living, celebrating the body of Christ. Can you experience God outside the bricks and mortar of a steeple-topped building? Absolutely. But, there’s something holy and essential and irreplaceable about the Spirit of God manifest among His people.

If you can understand the desire to worship with God’s people, you can understand what David was feeling in his exile in the desert. There he stood, looking back across the barren desert sands to the horizon beyond which Jerusalem, the city of God, sat without him. There the people of God went about their lives and worshiped God together. He remembered the great feast days with their singing and pageantry. As he squinted at the horizon and felt so keenly his separation from God’s people, he cried out in the pain of the gaping empty place in his heart. David ached for communion with God and the community of God.

In the midst of the lonely desert road, what are you to do? Praise God with every part of your body, mind, and spirit. Learn to praise God regardless of your personal circumstances, and you’ll see miracles occur. Your heart and mind will be renewed. Your perspective will widen panoramically. And your attitude toward God will never be the same.

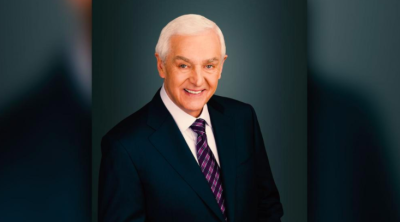

The above is an adaptation of Dr. Jeremiah’s soon-to-be-released book,“Shelter in God”

Dr. David Jeremiah is among the best known Christian leaders in the world. He serves as senior pastor of Shadow Mountain Community Church in El Cajon, California and is the founder and host of Turning Point. Turning Point‘s 30-minute radio program is heard on more than 2,200 radio stations daily. A New York Times bestselling author and Gold Medallion winner, he has written more than fifty books.