Why go to Mars?

NASA Administrator Jim Bridenstine has renewed his vow to put astronauts on Mars by as early as 2035. The head of America’s space program says we’ll start by going back to the moon, where we can test the technology necessary to make a much longer voyage to the Red Planet.

But the whole project to put boots on another planet—something incredibly expensive, dangerous, and time-consuming—raises an interesting question: Why should we do this?

Back in the sixties, the obvious answer for why we should go to the moon was to beat the Soviets. The space race, like the nuclear arms race, carried enormous military implications.

And then there was the symbolic victory, which was won when Neil Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin planted the Stars and Stripes on the lunar surface.

But there was a third reason for space exploration back then—which, unlike the other two reasons, still applies now.

In last year’s movie, “First Man,” Neil Armstrong, played by Ryan Gosling, finds himself forced to justify the space program to the public and to public officials, not to mention his own family, as accidents accumulate and the cost in lost lives mounts. Pointing beyond practical things like military supremacy, Armstrong, in the film, argues that the ultimate reason for going to space is that it is a worthy undertaking—something human beings were made to do.

“It allows us to see things,” he says, “that maybe we should have seen a long time ago, but just haven’t been able to until now.”

Looking back on pictures from a lunar mission, especially the photo of Earth rising over the moon’s surface—it’s hard to disagree with him.

His answer reminds me of a scene in “The Voyage of the Dawn Treader,” the third Chronicle of Narnia, in which the Dawn Treader’s crew must choose whether to sail on toward an island cloaked in forbidding darkness or turn back to safety.

When one of them asks, “What manner of use would it be ploughing through that blackness?” Reepicheep, the bravest crew member despite being the smallest, rebukes them for their faintheartedness.

“Use?” the mouse replies. “If by use you mean filling our bellies or our purses, I confess it will be no use at all. So far as I know we did not set sail to look for things useful but to seek honour and adventures. And here is as great an adventure as ever I heard of…”

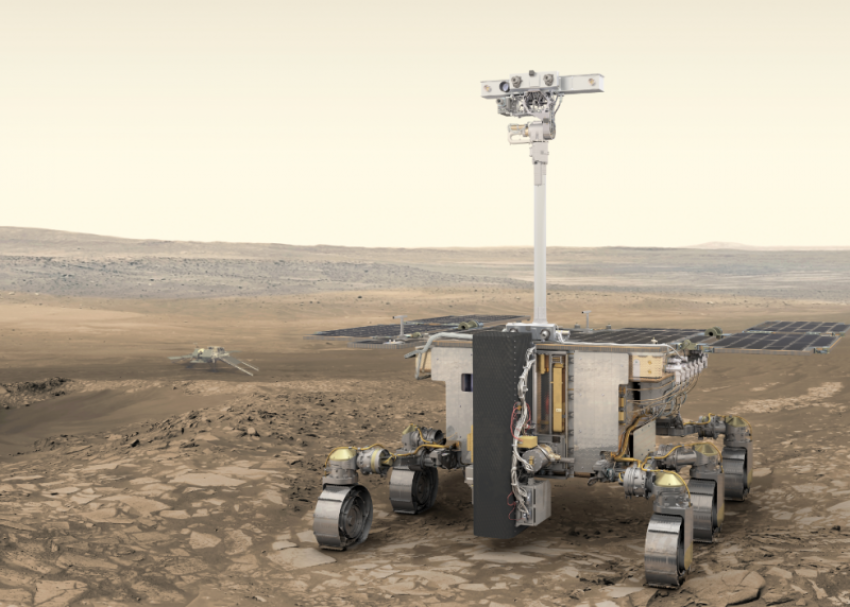

And so, they sail on. If NASA’s plans are realized, so will we. With sincere apologies to Reepicheep the mouse, I think the renewed push to put astronauts on Mars is a sign of something uniquely human. The urge to venture beyond our horizon and discover—even in the face of seemingly impossible obstacles—is a dead giveaway that we’re not like all the other creatures, or even like the robots and rovers we build and hurl into space.

We’re made in the image of God, and His original mandate to take dominion over all of creation still rings in our hearts and in our ears. For most of human history, gravity prevented us from taking dominion over anything beyond this planet. The rest of creation still awaits us.

This urge points to something true about even those who don’t acknowledge or believe in the One whose image they bear. Every scientist who peers through a microscope, every mathematician who solves a seemingly impossible problem, and every astronaut who has slipped the surly bonds of Earth knows how asking what use these things are simply misses the point.

Of course, many human adventures turn out to be useful. But the real question to be asked is not what purpose our discoveries serve, but what purpose we serve. According to Scripture, God placed us here to rule creation, to steward it, to bring it to flourishing, and in the process of witnessing all He has made, to echo His glory back to Him.

You know, whenever people do set foot on Mars, I hope there are some Christians among them. Not because they’ll necessarily be better astronauts, but because they will be able to better appreciate why they’re there.

Resources

Humans can land on Mars by 2035, NASA chief says, Chris Ciaccia, Fox News, October 22, 2019

Originally posted at BreakPoint.