10 influential Protestants for me

Yesterday on twitter there was a challenge to cite 10 most influential Protestants shaping your worldview. I gladly chimed in with my own, and here’s some elaboration:

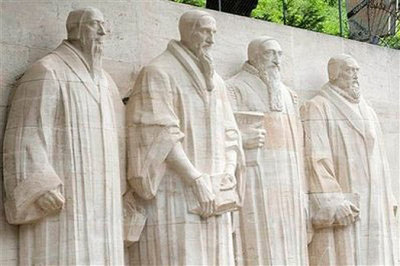

Martin Luther: Since he launched the Reformation, he must rank on this list, not just as religious reformer but as a founder of the faster paced and more egalitarian modern world. Unintentionally, he was the force behind modern democracy, with mass literacy, individualism, nation states, human rights and an expectation of equality. His stress on the dignity of all work fueled modern capitalism. His leaving the monastery for marriage further sacralized the family. He was a tireless machine, churning out endless translations, commentaries, sermons and hymns. He was brilliant, devout, fearless, sometimes bigoted, often intemperate. Luther was the continental divide of the last millennium. He’s always been a force in my mind.

John Calvin: Methodists like me aren’t supposed to embrace Calvin because of predestination, which was never his emphasis. He turbocharged the Reformation and also was central to molding the modern world. Lutherans were mostly Germanic and accepted the political and social status quo. Calvinists were international and revolutionary. They sternly feared God and sought to conform the world to His purposes. Their angst over salvation and calling created a social dynamism that electrified societies politically and economically. Calvinists were dangerous to tyrants. And Calvinists, unrestrained, could be tyrants. Sometimes they didn’t know when to stop. Calvin approved the burning of Servetus, a Socinian (Unitarian) for heresy. But when Calvinists are on the right path they are unstoppable. I’ve always been intrigued by and appreciative of Calvin and his followers. Once in the college library, I randomly examined his Institutes of the Christian Religion, and I reassuringly spotted a passage promising any believer fretting about salvation was already secure, as the nonbeliever would not worry.

John Wesley is the father of Methodism and his movement of personal holiness transformed Britain and early America. He was largely temperate and wise, a superb organizer, confidently Protestant but also apostolic and catholic. Unlike Luther and Calvin, he lived very long and toiled until the very end, maximizing each one of his nine decades. Wesley faced down angry mobs and could comfortably speak to both intellectuals and illiterates. He’s a father of modern evangelicalism but also stressed the centrality of the institutional church. Wesley was not a systematic theologian like Luther and Calvin but he published rich sermons, tracts and correspondence. The tradition he founded, stressing divine grace for all people, for reasons he likely did not foresee, became perhaps the most egalitarian of all major Protestant traditions. I think of him every Sunday when I attend a Methodist church.

Francis Asbury was Wesley’s apostle to early America, which he fearlessly crisscrossed and evangelized. He lacked Wesley’s erudition but more than equaled Wesley’s energy as the organizing force of what became America's largest church. His journal is a classic of early American religion. By making America Methodist, overshadowing originally dominant Calvinism, he also made it more democratic. Wesley was frugal but he had a nice house, a wide family, and a regular income. Asbury was alone, homeless, and scrounged what he could for the denomination he was building until he dropped dead from his labors. He was holy but supremely practical. Asbury opposed slavery, preached often to black audiences, and ordained black clergy, but he knew the limits of what he could do, leaving the rest to God and posterity. I’ve always admired Asbury.

Peter Cartwright was ordained by Asbury and represented the next generation of frontier circuit riders who lived long enough to see the backwoods civilized and Methodism become dominant. His memoir colorfully recorded his career, in which his many confrontations across decades resulted typically in Methodist conversion or calamity. He told Andrew Jackson that God esteemed him no more than any pagan from Africa. He bumptiously battled rival Baptists and Calvinists in the ferment of early American revivalism. Cartwright unwisely ran for Congress against Abraham Lincoln, whom he later admired, and he fortunately lost. I read Cartwright’s memoir as a young man and revered it as nearly canonical.

Dwight Moody was the prototype of the modern evangelist who speaks to urban crowds in theaters and stadiums with the goal of tallying conversions. He was a Congregationalist chaplain in the Civil War who appreciated from the battlefield that life can be short and eternal destinies must be decided. As urban Protestant churches became uppity, he strove to reach the less respectable unreached in America’s newly sprawling cities amid dramatic industrialization. He was simple and decent and sanctified. An optimist, he once asked God not to overwhelm him with more blessing lest he be unable to absorb it all. Reading his biography as a young man was deeply inspirational.

Less optimistic than Moody, Reinhold Niebuhr as German Reformed pastor and theologian addressed the dark complexities of American Christianity, urging systemic social reforms but cautioning against hubris about accomplishment in this world. Everyone, including the saintly elect, are influenced by self-interests and limited vision, even at their best. He understood America’s Calvinist and revivalistic history, which explained for him his nation’s strengths and weaknesses. Niebuhr urged America to lead in WWII and the Cold War but also warned America not to exult in its own supposed goodness. Hope in God but not in yourselves, Niebuhr implored, with Protestant gusto. He is the inspiration for our Providence: A Journal of Christianity and American Foreign Policy.

Everybody loves C.S. Lewis for his literary faith and charming ability to interpret Christianity with generosity and ironic insight. He’s endlessly sensible and portrays the path to faith as the logical conclusion to any carefully considered life. An Anglican, he was not entirely a conventional Protestant. He believed in purgatory and had a Catholic leaning view of salvation. Lewis tried to broadly advocate for orthodox Christianity in all its major streams. His message is successfully timeless and I much appreciated him as a young man and still do now.

Francis Schaeffer was a Presbyterian pastor turned Christian apologist and historiographer who created a Calvinist social theory that inspired contemporary Evangelical political witness and activism. He was an enthusiast for Christian Civilization without minimizing its failures, and he stressed the Reformation as the basis for modern ordered liberties, which he saw as deeply threatened by secularism. As a generalist, he was not always right in the details but his wider perspective was intellectually uplifting for a smarter evangelical public engagement. I read his works as a young man and was profoundly influenced and encouraged. Sadly, not many read him today.

Thomas Oden is the only Protestant on my list whom I personally knew. He was the foremost Methodist theologian of the late twentieth century. Urged on by his Jewish colleague Will Herberg, who thought Tom’s liberal Protestantism superficial, Tom studied and became committed to the Early Church Fathers, who persuaded him to embrace orthodoxy. Tom adorned his patristic faith with the Wesleyan distinctives of his own background. His works were expansive and unusually admired by Mainline Protestants, Catholics, Eastern Orthodox, and Evangelicals. His systematic theology included insights from all those traditions. Tom was ferociously attached to Methodism and its renewal, saying he would never leave the church of his baptism. As an older friend, he was endlessly encouraging and gracious. In his final years, speaking in a whisper, he sounded apostolic.

These ten Protestants have influenced me. Who’s influenced you?

Originally published at Juicy Ecumenism.

Mark Tooley became president of the Institute on Religion and Democracy (IRD) in 2009. He joined IRD in 1994 to found its United Methodist committee (UMAction). He is also editor of IRD’s foreign policy and national security journal, Providence.